My favorite sandwich is a Monte Cristo. It’s decadent, perhaps a little unhealthy, but delicious. Unfortunately, it used to be a more popular item at restaurants, especially diners, across the country, but in more recent years it has become harder and harder to find a proper one. What do I mean by proper? Let me explain. But first a digression that’s necessary to answer that question.

What is a Monte Cristo sandwich?

Defining a Monte Cristo is harder than you might imagine. Most sandwiches have a simple recipe so that if you order one, you can pretty much know what you’re going get. Think a B.L.T., Peanut Butter & Jelly, or a Philly Cheesesteak. Sure, there may be a few variations here and there, some additions perhaps, but the core sandwich is consistently the same and it will be what you expect. This is not the case with a Monte Cristo. Not any more. Most writers I’ve read tend to talk about a Monte Cristo in a vague way, defining it numerous ways, with lots of leeway about ingredients or processes, and giving credence to all sorts of variations that change its core essence. The Denver Post has an article that lays out a lot of possible variations. Frankly, I find it incredibly frustrating.

So while many food writers very loosely define a Monte Cristo, for me, it’s much more of a specific sandwich. My Monte Cristo is as follows: turkey, ham, and Swiss cheese (additional or added cheeses are acceptable) between three pieces of bread. The sandwich bread is battered and deep-fried, giving the entire sandwich a hard crust. Then it’s dusted with powdered sugar and served with raspberry (or similar) jam.

The History of the Monte Cristo

The origin of the Monte Cristo sandwich is lost to history. The most likely version is that it was based on the French Croque Monsieur, defined as “a hot sandwich made with ham and cheese.” Apparently, “the name comes from the French words croque (“crunch”) and monsieur (“gentleman”).” Another account says it’s “a grilled cheese sandwich consisting of Gruyere cheese and lean ham layered between two slices of crustless bread, fried in clarified butter and made in a special grilling iron with two metal plates.”

Another account states, without any evidence, that “historical records claim that the Monte Cristo sandwich was first served in 1910 in a café at Boulevard des Capucines in Paris.”

How it came from France is anybody’s guess but most accounts seem to suggest it had been introduced in California, possibly at the Hotel del Coronado in the 1940s. But from around the 1930s through as late as the 1960s, American cookbooks used a variety of names for the evolving sandwich, such as a French Sandwich, Toasted Ham Sandwich, and French Toasted Cheese Sandwich Another early source for the sandwich was the Brown Derby restaurant in Los Angeles, who likely helped popularize it. The Brown Derby Cook Book, published in 1949, was the first cookbook to print a recipe for a Monte Cristo.

That’s pretty close to what it evolved into, at least from my point of view. My first encounter with a Monte Cristo was in 1969, when I was ten years old. My mother and I flew from Pennsylvania to Oakland to see my great aunt, who lived there at the time. Then we flew to L.A. and took a helicopter to Anaheim and went to Disneyland. The Blue Bayou restaurant that’s attached the Pirates of the Caribbean ride was trying to serve food that fit the New Orleans theme so the cuisine was French and/or cajun and when it opened in 1967 included a deep-fried Monte Cristo on the menu. I had my first in 1969, and it was still on the menu when I went there with my kids just over a decade ago. It has subsequently been taken off the Blue Bayou menu (not sure when) but you can still get two different kinds of Monte Cristo sandwiches at the Cafe Orleans, which is also in New Orleans Square at Disneyland. One is described as a “Battered & Fried Monte Cristo (Sliced Turkey, Ham and Swiss with Seasonal Preserves)” and the other as a “Battered & Fried Triple Cheese Monte Cristo Sandwich (Brie, Swiss and Mozzarella with Seasonal Preserves).”

In fact, some food historians credit Disneyland with helping to spread the popularity of the sandwich nationally, because so many people would come to the theme park, have a Monte Cristo, and then look for it back home, causing many diners and other restaurants to begin adding it to their menus after numerous customers had been asking about it.

Other Origins

In doing some more sleuthing, I’ve found a few accounts that seem to upend those Southern California origin stories. As you’ll see below in the section “The Name” there were hotels in the northwestern U.S., one in Washington and one in Colorado, both called the Monte Cristo Hotel, and both have anecdotal evidence that they originated the sandwich, or at least one called a Monte Cristo. What kind of sandwich it may have been is a mystery.

I’ve also found an earlier reference to the sandwich, from 1923 in the “The Caterer and Hotel Proprietors’ Gazette” from the January edition, which includes a line in an ad: “Sandwiches … Monte Cristo …. 50 c.“

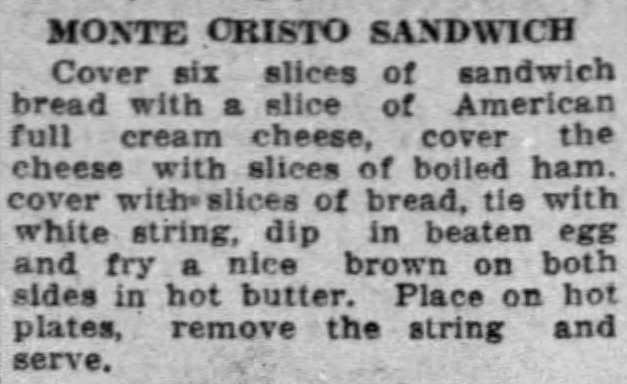

And it also appears to have been in print well before the 1950s, although not in a cookbook, but in a newspaper. This is from the Los Angeles Times, published May 24, 1924. Although it’s quite a bit different than the modern version.

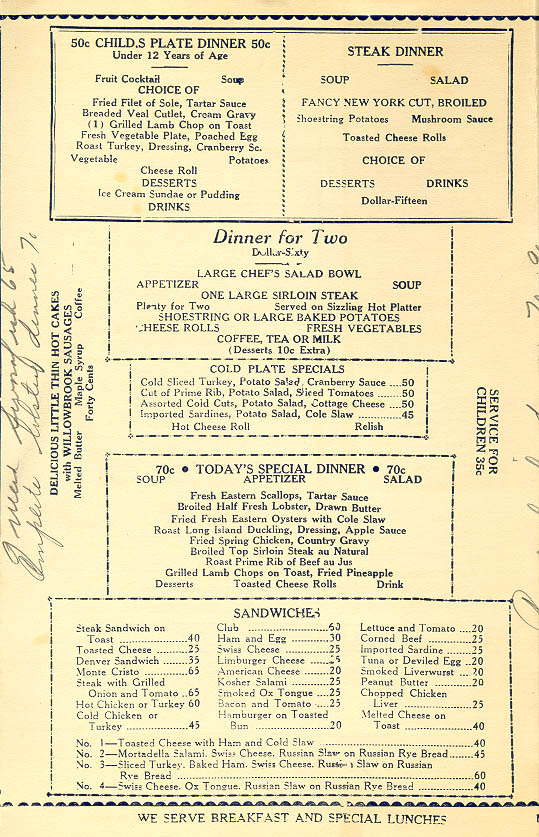

Cook’s Info has an illuminating article detailing numerous times a Monte Cristo has been mentioned in print. And I also found it listed on a menu from 1941 at a restaurant called “Gordon’s” on Wilshire Blvd., in Los Angeles. It’s listed under “Sandwiches” for 65-cents, but with no description.

The Modern Monte Cristo

So I grew up in a world where deep-fried Monte Cristo sandwiches were not terribly hard to find. Many diners served them, and for as long as I can remember, if it’s on a menu, I will order it. Every place I’ve lived, I’ve quickly figured out which diners had one and which were the best, and frequent those restaurants. But over the last decade or two, a increasingly larger number of people have become health-conscious, which seems to have led to two outcomes with regard to Monte Cristos. First of all, many diners and restaurants that used to serve a Monte Cristo took if off their menu. Presumably, they keep an eye on what sells and what doesn’t and adjust their menu accordingly, as you’d expect any savvy business to do. At other restaurants, they’ve kept the Monte Cristo on the menu, but changed the way they prepare it and/or how it’s battered.

What that means is that some restaurants have stopped making it in their deep-fryer and are instead pan frying it or grilling it. Another change is that many use essentially an egg batter similar to what’s used to make French toast. And no, those changes do not result in a bad sandwich. It’s still quite tasty, and I even can enjoy it. But to my way of thinking, it’s not an authentic Monte Cristo. I know I’m in the minority here, especially among food writers who arguably know more than I do about cuisine. But I can’t shake the feeling that the difference between deep-frying something versus simply pan frying it is so so vast that the result is two very different sandwiches. It’s not a simple variation, it’s much more than that. It’s not like adding something extra or making some small change in the cooking. But numerous websites by food writers and bloggers claim that a Monte Cristo can be pan-fried, grilled or whatever (I wouldn’t be surprised to find someone saying it was okay to boil it at this point). Similarly, a lot leeway is given to the batter as well. It’s apparently acceptable to dip the bread in anything from French toast to whatever you have lying around.

If I sound somewhat salty, that’s because I am. I’m certainly no food expert, but to my mind most named sandwiches are fairly well-defined, with a specific list of basic ingredients (which often are part of the definition) along with a very particular method of preparation. If you change any of those, then it’s no longer that specific sandwich and is more likely either a completely new creation or a variation on the original. So what I feel so many food writers have done is change their definition of the sandwich to fit the changing trends in how restaurants are making them in more modern times. To be fair, as it evolved from the Croque Monsieur (which is pan-fried), early recipes did indeed call for pan-fried, fried in butter or grilled. But I would argue that its evolution to a deep-fried sandwich (plus fixing other items as core ingredients) completed its journey to what a Monte Cristo became, most likely beginning in the late 1950s or 1960s. So as many restaurants backtrack (for health reasons, or more likely as cost-cutting measures) and have stopped deep frying it, food writers have gone along with it, following the trend rather than calling them out. In the end, I think it’s a bit dishonest to call a Monte Cristo that’s not deep-fried a Monte Cristo. For me, and I suspect many others, that’s the expectation. I wouldn’t be happy if I ordered a B.L.T. only to find they no longer include the bacon in it because it’s unhealthy and cheaper to prepare. If you’re offering a Monte Cristo that’s pan-fried, you’re not offering a Monte Cristo, at least not an authentic one.

It’s a bit like Hazy IPAs. Despite their popularity, it’s hard to argue that they’re truly part of the IPA family. They deviated so far from the original IPA guidelines as to make those guidelines almost meaningless. And like the pan-fried Monte Cristo, they can still be a good beer, but at a minimum they should not be called an IPA. But I have as much chance of changing how modern food writers define a Monte Cristo as I do stopping Hazy IPAs from being called that.

Other variations, especially early in the evolution of the sandwich include chicken, instead of turkey. It’s always made with ham, but the second meat can sometimes vary. Swiss cheese, or more correctly American-style Swiss cheese, has become the standard cheese, but the earliest mentioned was cream cheese. I’ve also seen mayonnaise mentioned more than a few times. Never do that. Mayonnaise should never be in a Monte Cristo. Just hard no.

And finally, a word about the powdered sugar and dipping sauces. For me, a light dusting of powdered sugar is best, with a small dish of raspberry jam for dipping your sandwich into. Does it have to be raspberry? While I think raspberry is the best pairing, blackberry, strawberry or even black currant jam also seem pretty good. Occasionally, a carafe of maple syrup or pancake syrup will be substituted, especially with ones that use a French toast-style batter. I can see how that idea came to be, but this is another case where it’s such a deviation from the classic taste profile that it should be called by a different name. A number of modern ones I’ve come across use two kinds of cheese, and to be honest that’s a variation I love, because in my opinion you can never have too much cheese.

Luckily, since this is my personal quest, for my purposes I can call a Monte Cristo as I see fit. And it’s why I also call an authentic Monte Cristo the unicorn of sandwiches: because using my definition it’s become so difficult to find in the wild.

My Monte Cristo

So here are the most important elements in what I consider to be the ideal, authentic Monte Cristo Sandwich. People can certainly quibble with my choices, but this is what I consider it:

- 1. Bread: 3 slices of white bread. White bread seems best, although sourdough seems to work pretty well, too.

- 2. Batter: While most modern versions use something akin to a French Toast egg-sauce dip, I prefer a Monte Cristo that’s battered and deep-fried, with a beer batter or a beer-like batter, or something similar. For me the key is that the batter being deep-fried will create a hard crust.

- 3. Meat: Ham and turkey are the classics for me.

- 4. Cheese: Swiss cheese, American-style Swiss cheese or Gruyere is the best cheese to use. As far as I’m concerned it pretty much has to be a Swiss cheese, although I do like it when it’s made with two cheeses, ideally one of them Swiss, and the other something like cheddar.

- 5. Topping: A light dusting of powdered sugar is required.

- 6. Dipping Sauce: The best dipping sauce is raspberry jam, although blackberry or black currant can be good, too. Other berry jams could work, like strawberry or grape, but generally speaking other fruit jams and maple syrup should not be substituted.

- 7. Cooking: The key for me is that the Monte Cristo must be deep-fried, not merely pan-fried or grilled. Pan-frying in enough oil can produce an adequate crust, but deep-frying seems to work best, and gives the sandwich the desired crisp crust.

The Name

While no one seems sure where the name comes from, at least one theory is that it’s taken from Alexander Dumas’ popular novel, The Count of Monte Cristo, where in the novel Monte Cristo is an island that figures heavily in the plot. It’s a real island, though is usually spelled as one word: Montecristo, and is located “in the Tyrrhenian Sea and part of the Tuscan Archipelago. Administratively it belongs to the municipality of Portoferraio in the province of Livorno, Italy.” And while sure, maybe that’s the case, I don’t really understand any connection between the novel and the sandwich.

Another mostly overlooked possibility is its name comes from the town of Monte Cristo, Washington, a town founded in the 1890s during the gold and silver rush in that area. It was later a resort town but today is a ghost town. Unfortunately, there is no evidence they ever made a sandwich named for the town, apart from some personal anecdotes from people growing up in the area.

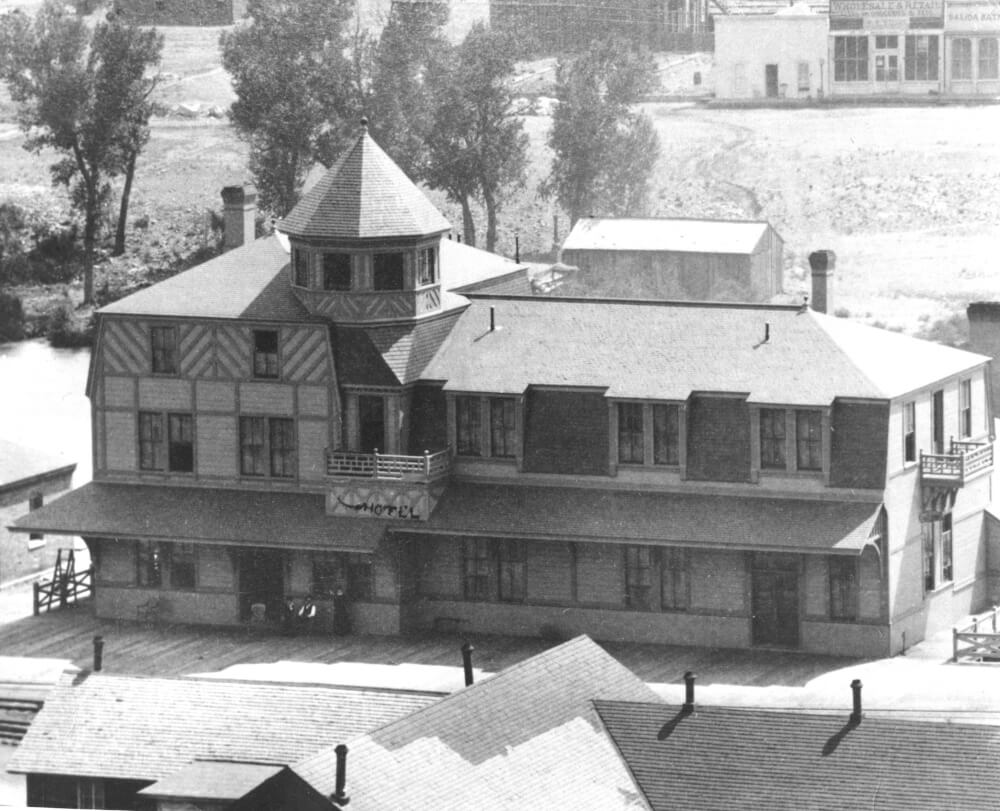

Another tantalizing possibility is that it originated at the Monte Cristo Hotel of Salida, Colorado. It was founded in 1883 but closed in 1941. A veteran chef who lived in the area apparently saw references to the Monte Cristo as a sandwich made at the hotel at the local Salida library.

Although there’s also a Monte Cristo Hotel in Everett, Washington, and some online sources claim the same thing about this hotel, that it originated the sandwich, but again there’s no real evidence I could find to confirm it. Why did this hotel come to be called Monte Cristo? Apparently there’s a Monte Cristo mining region in the Cascades Mountains, which runs from B.C., Canada down through Washington, Oregon and Northern California.