![]() vs.

vs. ![]()

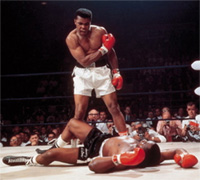

Yesterday Slate Magazine, in the guise of Field Maloney — who claims to drink beer — declared beer all but dead and wine standing over it in the boxing rink taunting it ala a triumphant Cassius Clay after he defeated Sonny Liston.

The only problem with that sentiment and, indeed, much of his article is that it simply isn’t true. He uses old and questionable statistics and ignores the entire craft beer segment of the marketplace, something like 99% of the breweries out there seem to be under his radar. That’s pretty remarkable given that he claims to like the very stuff he’s bashing. You’d think he’d know just a little bit more about it, wouldn’t you? He does briefly mention craft beer, but only to suggest that we’ve all pilfered wine’s descriptive language. Apparently wine drinkers own the term “floral.”

But every other time he uses the word beer, he’s using it in a very narrow sense. By beer, Maloney means Bud, Miller, Coors and maybe Pabst and any brands owned by the big guys. Period. Because the way he describes “beer marketers” and “American beer executives” it’s abundantly clear he’s not talking about the small fry.

While using support for his position that beer is down and out he uses the infamous 2005 Gallup poll that seemed to indicate that people were beginning to prefer wine to beer, calling the findings “astonishing.” As noted in the sidebar, however, the 2006 poll results returned beer to the top spot, which is where it had been virtually every year before 2005, too. The 2005 results were obviously anomalous but despite that it keeps showing up in print, used to push various agendas. Beer outsells wine roughly four to one, and has done so for many years. That statistic is easily verifiable, unlike what people say about what they like — their so-called preferences — and so it’s a far more accurate portrait of the alcohol landscape. And while overall consumption has been steadily decreasing for many years, and even if we allow for Maloney’s uncited figure of wines sales having doubled over the last ten years (from a small number to begin with), beer is still wildly more popular than wine and will continue to be for the foreseeable future.

The sidebar continues by dismissing the 2006 poll, despite the fact that every poll prior to 2005 agrees with it, saying “[s]till, while wine consumption has grown steadily in this country, beer consumption has remained flat. (The one exception to this trend is craft beers, which have enjoyed double-digit sales growth in the last few years. But craft beers command less than 5 percent of the domestic beer market. Anheuser-Busch alone, by comparison, controls about 50 percent of it.)” What I take away from that bit of tortured analysis is that because craft beer doesn’t represent a big enough piece of the pie, then it’s not worth talking about and it’s not indicative of any trends. Yet Anheuser-Busch has test-marketed or rolled out last year alone something like fifty new products that give the appearance of being craft beers to compete with this segment of the industry. They certainly wouldn’t be spending all their resources on such folly if craft beer wasn’t having an impact on them, so Maloney’s off-hand dismissal of craft beer seems misleading and counterfactual.

I’d love to see figures on big wines vs. boutique wine sales as a percentage of the total (though I suspect definitions are every bit as difficult as in the beer world) but I suspect Maloney doesn’t discount those small wine producers in quoting wine statistics and the gains they’ve made the way he discounts craft beer. And he appears to entirely ignore box wine, jug wine and other cheap wines made in vats the size of Montana, as if all wine was hand-crafted. The notion that all wine is fine wine is every bit as specious as saying all beer is industrial.

Brewers will no doubt get a kick out of this zinger. “The hallmark of beer is consistency: A brewer strives to make batch after batch of Pilsener so it tastes the same—and often succeeds without much difficulty.” So much for the author’s earlier jab about beer being the “result of a complicated process of manufacture.” If it’s not too difficult to make beer consistently, it must not be that complicated after all. That series of statements seems more than a little insulting to me. Most, if not all, of the winemakers I have met have the utmost respect for brewers and do think it’s harder or more complicated to make great beer than great wine. A winemaker I sat next to at a dinner at Mondavi many years ago told me that she thought what they did was easy compared to making beer and that the grapes did all the real work. So yes, I think there is something to beer being more of a complicated affair than wine, but I don’t see why that makes it any less of an art than he appears to believe is the case with winemaking.

Maloney also claims that it was our society’s “shift from an agrarian society to an urban, industrial one” that made beer our drink of choice, because mass production displaced hand made drinks, such as “hard cider (the rural drink of choice), rum, and whiskey.” But didn’t many rum and American whisky brands that are still with us today also get their start during the industrial revolution? If so, then why is beer the bad guy here? Also, he states that beer started to outsell cider “around the time of the Civil War,” but I’m not sure that’s true. I remember reading that cider’s popularity throughout the country did not wane until Prohibition, and that until that time it continued to outsell beer. If that’s true — I’m trying to remember and find where I read that — then it continued to be quite popular through many decades of industrialization. And that seems to contradict his premise that mechanization caused or was responsible for beer’s popularity during the 19th century.

Interestingly, additional criticism of Maloney’s article came from an unlikely source. Nick Fauchald, Senior Associate Food Editor at Food & Wine magazine, penned a rebuttal wonderfully entitled Beer to Wine: “I’m Not Dead Yet” in which he also cites craft beer’s recent gains and suggests the following.

Slate and other outlets sounding the beer death knell are missing one very important point: It’s the generic-tasting, mass-produced beer (Budweiser, Miller and their ilk) that Americans are waving off. American craft beer is still alive and kicking, experiencing its biggest growth since the microbrewery gold rush of the 1990s.

Slate even in mentioning craft beer manages to do so each time with a dismissive tone that makes it sound irrelevant to the discussion. But that ignores over 1400 independent small to medium-sized breweries and brewpubs successfully providing craft beer locally, regionally and even nationally. Craft beer is part of the slow food movement, part of organic food lifestyles, and a part of eating and drinking locally campaigns. It’s just one of many gourmet products, like coffee, chocolate, cheese, bread and many others, that have literally changed the way we perceive and think about them. Craft beer has raised the quality and status of American beer to the point where it has the respect and envy of beer lovers around the world. It’s only here in the U.S. that it gets so little respect.

Unfortunately, a lot of that criticism comes from food and wine sources. I don’t know or understand why so many wine and food writers appear to feel threatened by beer. I don’t know if it’s simple ignorance or malicious snobbery. Is it a kind of good ole boys mentality that can’t abide beer stealing some of their thunder? That sounds almost ridiculous, except that it seems to happen time and time again. Perhaps the real question is why they feel the need to pit the two against one another in the first place? Is it really a competition? Is it really us vs. them? I certainly don’t want to believe that’s it, because I love wine, too, as do most of the hardcore beer people I know, including other writers and brewers. And all of the winemakers I know love beer. So it comes down once more to the question I’ve asked time and time again: why can’t we all just get along. Seriously, I’m not just being rhetorical, but why can’t wine and beer seem to coexist and be supportive of one another? Why do Maloney and so many others feel the need to bash beer in order to lift up their preferred libation? It’s not everybody, obviously, as Nick Fauchald from Food & Wine nicely demonstrates, but it seems to me an awful lot of people who write about wine and/or food have it in for beer. Why is that? It’s got me crying in my beer, because it just doesn’t have to be that way.

UPDATE: Jess Sand over at the wonderful Bar Stories added a very thoughtful and lengthy diatribe on the same Slate article, as did Stan Hieronymous over at Appelation Beer.

Jay, once again you make a million wonderful points. I was quite surprised at the Slate article’s anti-beer attitude couched as thoughtful analysis. You can read my own response to it at Bar Stories:

http://barstories.blogspot.com/2007/05/pastoral-nostalgia-or-blue-collar-chic.html

Re: Cider history in thr U.S.—It’s funny you brought this particular point up because I, too, was a little taken aback by the point that beer overtook cider in the late 19th c. After doing some digging myself (I can dig again and email my sources if you’re that desperately interested), I was left with the impression that while cider was indeed exceedingly popular during the 19th c, ale seemed to have been equally so. I think the author took the introduction of lager at that time (circa Civil War), and stretched it a little. Lager swasn’t particularly popular before then because the refrigeration-during-brewing/storing-technology just wasn’t up to par until that point. Hence his connection to industrialization.

That said, I don’t know about sales numbers. And lastly, the whole agricultural-vs-industrial product argument is bunk in my book (see above-mentioned post)

Best,

Jessie

Thanks for the link, Jay!

Jay,

I usually ignore nitwit writers like Maloney who make such sweeping pronouncements about craft beer, but when beer history is discussed, I have to chime in.

Beer did take over cider as a national drink, but for numerous reasons. Part of the general trend towards beer, actually lager beer, over cider was due to the second wave of immigration, especially Germans. Cider consumption was one of the last vestiges of English influence as Americans turned instead towards establishing their own national food and drink, a trend that began with a new country and the search for a national identity. Of course the fact that we tweaked foreign food and drink and made them our own is another story.

Not only were Americans moving towards beer as a favored drink, they were moving from ale to lager. The shift in taste from ale to lager beer took time, but Americans and other immigrant groups eventually grew a liking to lager beer, not coincidentally after a Civil War excise tax was imposed on beer and the already tax-laden distilled liquors in 1862. While beer was taxed at $2 per thirty-one-gallon barrel, the significantly higher-based liquor tax drastically changed the drinking habits of the everyday man, turning him from the now costly whiskey to lower-priced lager beer. By 1865, a federal tax was being imposed at the exorbitant rate of $62 per barrel on whiskey, and as a result, German lager was evolving into the affordable drink of the working class with help from the Internal Revenue System.

As settlers pushed beyond the Mississippi, they were accompanied by brewers, mostly Germans, who were looking for a place to settle down, establish a lager beer brewery, and develop a market. In their path, lager beer breweries sprang up in such German-populated areas as Detroit, Milwaukee, Chicago, St. Louis, and even settlements in Texas, while some East Coast breweries too began to abandon ale in favor of lager. As a balanced accommodation for those customers who insisted on drinking ale, some breweries deferred and brewed both types of beer.

It’s also interesting to note the correlation of the growth of the U.S.beer industry as Germans were fleeing the post-1848 political turmoil in Europe and arriving in the U.S. The German-American brewers took their beer seriously and pushed hard the concept that the brewing of beer should take a more scientific approach. This philosophy, along with the employment of mechanical refrigeration, was being demonstrated in Europe with impressive results in the quality of European beers. Many of the limitations that had plagued American brewers since the colonial era were being overcome by the scientific discoveries and inventions of the Industrial Revolution; the adaptation of a number of these findings directly benefited the U.S. brewing industry.

As for your thought that cider held high popularity until Prohibition? It didn’t. Just look at the entire saloon system. Did you ever hear of cider saloons? Did you ever hear of names like Schlitz or Rupert being bantered about when speaking of cider or a national cider industry? Cider’s fading role as a popular drink was sealed as British-American culture was replaced with food and drink influences from a third wave of immigration from Poles, Hungarians, Italians, Lithuanians, Jews, Russians, Greek, Turks, and even more Irish, Germans, Scots, and English entered the U.S. through various ports of entry from around 1885 to the beginning of World War I. A majority of these new immigrants would settle in big cities such as New York, Buffalo, Boston, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Chicago and bring with them food and drink tastes with a decidedly foreign flair.