Ugh, why do people keep defending low-calorie light diet beer? It’s an abomination. It should go away. It’s a marketing trick. It’s the best selling kind of beer in America, and defending it is the equivalent of complaining about the “War on Christmas” or the “War on White People.” Yes, sales have been slipping lately, with more people choosing beer with flavor, but certainly not enough to put much of a dent in the sheer volume of this dreck. Yes, many, if not most, craft beer drinkers choose not to drink it and some even bash it as something not worthy of respect. Well, I am one of those people. Not everything deserves our respect. I respect how difficult it is to make, but in the end that’s not the standard I want to use for how I choose what to drink. Degree of difficulty may be fine for Olympic gymnastics or diving, but taste is far more important to me when it comes to my beer.

So please stop telling me I must love it because it’s really, really hard to make. I get that. I marvel at the technology that must be employed, the sacrifice of ingredients to keep it lighter in color and flavor, the loving care taken to make something that … should … not … exist, and would not exist if not for the Herculean effort to make it. It’s unnatural. So why go to such an effort to make something nobody wanted in the first place? Why spend millions of dollars to convince people they should be drinking it? Why create new processes to create Frankenbrew in the laboratory when ordinary beer was perfectly fine, thank you very much? Anyone, anyone? Bueller? Did anyone say “money?” Show ’em what they win. They win a beer landscape dominated by beer that tastes as close to water as technologically possible. Hooray! Drop the balloons, throw the confetti and start the singing and dancing.

Earlier this summer, David Ryder, Vice-President of Brewing for MillerCoors wrote an op-ed piece in the Chicago Sun-Times entitled In Defense of Light Beer, in which he trotted out the old saws about light beer. The fact that the two top-selling products his company makes are Coors Light and Miller Lite should, of course, have made anyone suspicious of his motives and question any arguments in his editorial piece. The fact that the Sun-Times ran such an obviously biased piece is rather sad, I think. It’s a bit like asking Lee Iacocca to defend the Pinto. You can’t expect objectivity.

But now there’s another article telling me I have to respect light beer, this time in a magazine I actually read, and usually enjoy: Mental Floss. The piece, Scientific Reasons to Respect Light Beer is written by Jed Lipinski, who appears to not be a frequent writer about beer, not that that should matter. After a few anecdotes from craft beer fans disparaging light beer, he launches into his defense:

What few drinkers know, however, is that quality light beers are incredibly difficult to brew. The thin flavor means there’s little to mask defects in the more than 800 chemical compounds within. As Kyler Serfass, manager of the home-brew supply shop Brooklyn Homebrew, told me, “Light beer is a brewer’s beer. It may be bland, but it’s really tough to do.” Belgian monks and master brewers around the world marvel at how macro-breweries like Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors have perfected the process in hundreds of factories, ensuring that every pour from every brewery tastes exactly the same. Staring at a bottle, it’s staggering to consider the effort that goes into producing each ounce of the straw-colored liquid. But perhaps the most impressive thing about light beer isn’t the time needed or the craftsmanship or even the consistency, but how many lives the beverage has saved.

And there’s degree of difficulty again. Is light beer really a “brewer’s beer?” I have to question that one. But even more of a howler is how “Belgian monks and master brewers around the world marvel at how macro-breweries like Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors have perfected the process.” They may find the technology or the process interesting, they may even be impressed by the effort, but I think you’d be hard-pressed to find a brewing monk who prefers Bud Light to Duvel, or Orval, or Westmalle. Can anyone really think the average German brewer “marvels” at Miller Lite when compared to the average everyday Bavarian beer? Or that the brewers of England think Coors Light better than the average cask hand-pulled from their local pub? In fact, until the rise of low-calorie diet beer, most Europeans, when referring to “light” beer, thought of light in terms of color, as the German helles (which means “bright” or “light”) or hell (an adjective for “light”). Also, he begins by referring to light beer as having “thin flavors.” Since when has that ever been a positive attribute for anything? When is “less flavor” something to strive for? Name another food product where the goal is to create a version with not as much flavor.

But then there’s that last bit, about how light beer has saved lives. Huh? Yeah, that was my response, too. Huh? And here’s the reason.

“Before it was light beer, it was “small beer.” A popular drink in late-medieval Europe and colonial America, small beer was necessary for certain civilizations to grow. In the days before Brita filters, beer staved off disease and dehydration by packing just enough alcohol to kill off pathogens found in drinking water.

Except that it wasn’t. One didn’t evolve into the other, in some natural progression. The two are not the same, apart from both being low-alcohol and beers. He even contradicts himself by saying that it was popular in medieval times and allowed “civilizations to grow.” Given that civilization was around for thousands of years before that period of history and that beer was there at the very dawn of civilization, I think we can safely say that “small beer” didn’t save mankind. Beer generally had a hand in keeping people healthier longer, allowing those with a tolerance for alcohol to prosper and procreate, but it wasn’t “light beer” that saved the day. If those people had to wait around for brewers to figure out they could use the second runnings of their strong beer to make a lower strength beer that they could sell for less, they would not have survived. Small beer was essentially a way to make more money, to re-use part of the brewing waste, first created by English brewers, although most brewing cultures also made a beer of lower strength that was essentially a table beer. Anchor Brewing has continued the English tradition by making a Small Beer from their Old Foghorn Barleywine Style Ale, and despite it being 3.3% a.b.v., it’s about as far from a low-calorie light diet beer as one could be.

Light beer was the brainchild of one man, who thought people would want diet beer. He was wrong, though he did come up with the process of how to make a low-calorie diet beer. Here’s the story, from an earlier post of mine:

The first low-calorie beer was created by Joe Owades, who, it must be said, had some very strong opinions about beer. He once told me that all ale yeast was dead and inferior to lager yeast. Around 1967, he created Gablinger’s diet beer, the first light beer, while working for Rheingold. It flopped. Big time. Not everybody agrees on what happened next. Some accounts credit Owades with sharing his recipe for light beer with Meister Brau of Chicago while others claim that the Peter Hand Brewing Company (which marketed Meister Brau) came up with it independently on their own. However it happened, Meister Brau Lite proved somewhat more successful than Gablinger’s, primarily due to its superior marketing. Miller Brewing later acquired Meister Brau, and in 1975 debuted Miller Lite, complete with the distinctive, trademark-able spelling.

But it took marketing the new low-calorie beer in a new way so that it removed the “diet” stigma to make it work. They had to trick people into drinking it. Miller’s famously successful “tastes great, less filling” campaign was the primary reason for the category’s success. But it was hardly overnight. It took fifteen years — from 1975 to 1990 — for Miller Lite to reach 10% of the market. Over that time, the other big brewers (loathe to miss out on any market share) introduced their own versions, such as Coors Light and Bud Light, so that whole segment of low-calorie beer was nearly 30% of the beer market by 1990.

Today, seven of the top ten big brands are light beers. Despite its recent dip in sales, it remains a $50 billion segment of the business and still hovers close to half of all beer sold in the United States. That fact, I find to be incredibly sad, frankly. What a great triumph of marketing over common sense and actual taste.

Which is why I hardly think anyone needs to be rushing to its defense. People are willingly drinking it in frighteningly high numbers. I can only assume they’re the same people who buy Wonder Bread, Kraft cheese, TV dinners and every other popular product, even when everybody knows better, healthier, tastier alternatives are available.

Owades supposedly saw the focus group data indicating that people were giving up beer to save calories. Remember, this was the 1950s. Of course, it seems to me the smarter decision would have been to persuade people that beer is not as fattening as they thought. That this is true means it probably would have been a much easier sell. The idea that beer is so fattening is something of a myth, just like the beer belly. It seems to me that if the beer companies at that time had thrown their millions of ad dollars into that message, things might be a lot better today. But they chose the harder path, one we’re all still paying for. Instead of changing the message, they went with “the customer is always right” approach and created a beer to satisfy the consumer’s misconceptions and incorrect assumptions. In other words, when the customer was wrong, they just went with it. When it tanked, instead of cutting their losses, they instead spent millions persuading customers something that wasn’t true; that beer was fattening, but drinking this “magic diet beer” would fix that. The first thing they learned was not to call it “diet beer.” It’s what pharmaceutical companies have learned how to do so well. They first come up with the drug, then create the condition it will cure, even if it didn’t exist before. Anybody remember “restless leg syndrome” before the drug that treats it came on the market?

Lipinski goes on to detail the technology and the steps in the process that big breweries take to create low-calorie diet beer. And even he admits it was a tough sell at the beginning, and how a barrage of advertising was necessary to make it succeed. So tell me again why I have to respect something that had to be sold to the American people through advertising and marketing and which would probably not exist had that advertising failed? If those ads had not worked, low-calorie diet beer could have just as easily ended up on the scrap heap with dry beer, ice beer or tequila-flavored beer.

Peter Kraemer, a VP at ABI, seems to believe part of the problem is with definitions. He claims that “‘light beer’ has lost all meaning over the years” and he “considers [regular Budweiser and Bud Light] both light beers.” In that, he may be on to something. Regular Bud and Bud Light were once judged at GABF as separate categories, but today are sub-categories under the umbrella “American-Style Lager, Light Lager or Premium Lager,” a category I judged a first round of this year. Indeed, even the technical differences in the four sub-categories are slight. I suspect that they may have been more different at one time, but as Anheuser-Busch finally revealed in a 2006 Wall Street Journal article, Budweiser Admits Flavor “Drifted” Over the Years. So regular Bud has been slowly “creeping” closer to Bud Light over the years. But the fact is they taste pretty similar, have not much difference in terms of calories and are separated only in the way they’re marketed. They remind me of the choice between 87 regular octane gasoline and 91 premium octane. I’m told they’re not the same gasoline but damned if it makes any difference to my car, and I’ve long suspected that it’s like an old Dave Berg cartoon I saw in Mad magazine where all the gas actually comes out of one big tank below the pumps, and really is all the same.

And why not, the driving force in these changes is being able to use less ingredients, making the profits higher. It’s not rocket science. Use less malt and hops, and it will cost less to produce the beer, all other costs being equal. Over a small batch or two, it’s probably not that much, but in vats the size of Montana, it makes a big difference to the bottom line. And that’s plenty of incentive to spend the ad dollars to convince people that the flavor you’re not tasting is what you really want, because it’s better for you, won’t fill you up and, besides, it still tastes great. Trust us.

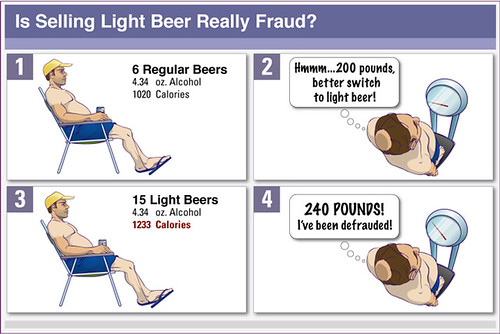

The other reason, or incentive, that the big brewers have for light beer is that having convinced people that they have less calories, people feel that they can actually drink more of them. And that’s what they end up doing. So by promoting them as healthier, diet beer, people end up actually drinking more calories. As The Litigation Consulting Report explains, in order to get the same buzz, that is the same amount of alcohol (which is also lower in most light beers), you’d have to drink 15 light beers to get the same alcohol that’s in six regular beers. According to them, this is known as the “compensation” effect and “is an issue in some product liability cases.”

But the diet aspects of beer already work for all beer, no reason to even sacrifice the flavor between the two. But since they’re admittedly both the same, you may as well avoid both regular and the diet versions in favor of something with actual flavor. That’s one of the biggest reasons I hate low-calorie diet beer: there’s simply no reason for it to exist. For most beers, have two instead of three and you’ll be ahead of the game. Drink smarter, drink better.

I realize I’m in the minority here, as every time I write about counting calories, people comment that they do actually watch their caloric intake, but I do not, and never have. I’ve gone over 50 years without counting a single calorie and, while I may not be the world’s healthiest man, I’m not the world’s worst either. And I’ve certainly never regretted choosing to eat or drink whatever I want. I find the slavish obsession to calorie counting absurd, but have come to recognize that many people really do care about them. I’ve written about this issue before, in Calories In Beer: Can We Please Stop?, Calories In Beer: Can We Please Stop, Part 2 and Read This, Not That. Life is undoubtedly about making choices, assessing risks and deciding what’s best for you.

Still, if you love beer, why defend low-calorie diet beer that is in every way as far from actual beer as possible? Everyone acknowledges it has less flavor. It has a few less calories, but stripping calories also strips … wait for it … flavor. But the difference between regular and diet beer seems so slight to me to be almost meaningless, especially when simply drinking one less beer would have roughly the same effect. If Budweiser has 145 calories in a 12 oz. bottle, and Bud Light has 110, drinking three diet beers would save you 105 calories. But have just two Buds, and you’d save 40 calories over three Bud Lights. Better still, choose two Samuel Adams Boston Lagers (160 calories) and you’d still save 10 calories over three Bud Lights or choose two Sierra Nevada Pale Ales (175 calories) and it will cost you only 20 more calories than drinking three Bud Lights would, though you’d still save 85 calories drinking two Sierra Nevada Pale Ales instead of three regular Budweisers. The point is that the caloric savings in diet beers are a sham. The differences are too slight to sacrifice so much flavor and enjoyment.

To sum up, diet beers were created in a laboratory to fill a need that didn’t exist. Making the beer that nobody wanted is incredibly difficult, and much harder than just making normal beer. To be successful, millions of dollars had to be spent on marketing and advertising to convince people to buy the thing that’s harder to make that they didn’t want in the first place. Finally, after nearly 40 years, and at least 20 that they’ve dominated the market, sales are starting to slip as people are choosing beer with more flavor instead. But rather than follow the shifting marketplace, pleas are being made that we should respect the beer nobody wanted that’s harder to make because … well, just because it is so danged hard to make and is a technological marvel deserving our respect.

As Lipinski wittily remarks in his closing sentence, he hopes his efforts at persuading you to respect light beer will “help you see the brew in a new light,” but there’s really nothing new in his arguments. His “scientific reasons” can only command your respect up to a point. I can respect the process, I can respect the technology, I can respect the effort made, but I still can’t respect the results. I honestly don’t understand how anyone can, quite frankly. With no disrespect to the many wonderful brewers who make low-calorie light diet beer, you can do better. You know you can. I have no truck with your skill as brewers or with the technology you wield so impressively. But I want a beer with more flavor. So until diet beer, like so many other diet products, tastes exactly the same as the more flavorful beers I prefer, I can’t give it the respect you insist it deserves.

Jay, I hear you. But light beer has a place in the spectrum of beer. I like craft, but I also like light lagers. What I’ve never understood is the vilification of light lagers as if it’s almost a moral issue. Miller Lite isn’t evil, it’s just a style of beer, just like that awful smoked bock you and I had in Bamberg 4 years ago.

I agree that they’ve found, or perhaps more correctly pushed their way into having, a place in the spectrum of beer today. I’d be happy to just ignore them, and most times I do. What always raises my hackles is when people rush to their defense, as if they need defending. Why that should be, I don’t personally understand, but it’s not something I can ignore. If sales are any indication, lots of people like them, and so they shouldn’t need anyone to persuade people to respect them. So why then am I so often lectured to that I MUST love them, or at least respect them, just because they’re hard to make. That’s what draws me into this, because that I don’t understand. For me, it’s a bit like every food. For almost anything you can name, there’s degrees of quality. For bread, there’s the popular but much-maligned Wonder Bread (WB). If people like it, buy it and eat it, I honestly couldn’t care less. But even WB buyers know that there’s better bread available. They see it right next to the WB on the shelf; the baguettes in the baskets, the sourdough rolls. No problem. But when WB starts talking smack and saying that they’re a better bread because getting all of the chemicals and vitamins into the bread requires a more difficult process than just baking a loaf of bread the old-fashioned way, and therefore I should respect WB more just for that reason, well then it’s a much harder sell. And that’s where I find myself. I don’t mean to vilify light beer, but when pressed I do find it to be a product that is too much science, not enough art. I find its history to be somewhat lacking. I just don’t like it, and that would be fine if it didn’t keep trying to be something that it’s not.

I honestly do respect the brewers who make it, and how they make it, but it still tastes of nothing to me. Plus, to my way of thinking there are plenty of better alternatives that are low in abv, but still flavorful. In my backyard, Trumer Pils springs to mind, but there’s a whole class of beers — Session beers — that accomplish the same goal as diet beers, but without sacrificing flavor. I respect those so much more because they didn’t trade one advantage for another.

You know, I often think of that smoked bock. It was perfect with the giant onion, the size of my head, filled with meat and topped with bacon. I can’t imagine it working in any other place, with any other food, but on that night: perfection.

Jay, Yes, that smoked bock was indeed pretty good with that onion smothered in gravy smothered in bacon smothered in eggs smothered in ….. etc. What a great night that was. If I’m not mistaken, we were eventually asked to leave.

My only parting point is that light beer is beer. Yes, it’s beer. I know it pisses a lot of people off that it’s beer, but it’s beer. I don’t see too many people defending light lagers…. maybe two articles a year versus 5k articles on craft. Light lagers have ethanol, bubbles, convenient packaging…… I am not ashamed to say that I enjoy light lagers on occasion, just as I enjoy a Jolly Pumpkin or a Lagunitas IPA or a whiskey neat.

It is beer, I don’t dispute that. Is it on par with all other beers equally? That, I’m not so sure about, because it didn’t develop naturally, organically or out of some real need. It was created artificially to fill a false need, and when that didn’t work a market was created to sell it to, primarily to increase profits. Am I being fair? Perhaps not, but as the undisputed champion of low flavored malt beverages, it’s hard to really give it the respect so many people seem to think it deserves.

People do seem to get very ego invested and feel challenged if others do not share their particular passion or even choice.

What’s always interesting to me is that people (and I catch myself behaving like this sometimes), become very emotional when hearing an opinion different from their own. About politics, I can understand it. About flavor choice, hard to fathom. It’s one thing if someone says, “You’re an idiot for liking rutabagas, or lite beer.” It’s different if someone simply says, “I can’t stand rutabagas and lite beer.” Even if they are

…the only things you eat and drink. As long as you are a Giants fan, I’ll bring my own beer and broccoli.

Jay, you are so on the money with this. I could not have agreed more. In fact, I have been saying this for years (about a product people just did not need), and the “Drink better, drink less” argument. Well done. Cheers.

PS: And there’s nothing better than a Wonder Bread sandwich with just mayonaise and bologna and a processed Kraft cheese slice.

Ha, that’s my 8-year old’s dream sandwich.

Great post, Jay! This geek sez that such brews have NO DEFENSE!

Miller Lite is the most tasteless beer I’ve ever drunk – I 1st tasted it when it hit the scene, & maybe only once or twice since – it was crap then & still is! Its “triple hopped” ads of the recent past were a joke! That beer tastes like it has one cluster/pellet/dram of hop oil (I’ve heard that Miller uses oil, rather than real hops/pellets) added every 20′ during the boil. Bud & Coors versions are slightly more palatable. I’d rather drink non-alcohol Kaliber, Clausthaler, or Hakkebeck than any of ’em. My favorite inexpensive light lagers are Yuengling (not yet available in CA) & Trader Joe’s Simpler times (6% ABV; contract-brewed in Monroe, WI; $3.49/6).

You hit the nail squarely on the head by attributing “Lite/Light” brews’ successes to marketing. The only “craft” brewer to jump on that bandwagon so far has been Jim Koch of Boston Brewing – & I think he should have been prosecuted for truth-in-advertising violations for his “I brew the best beer in America” claims (when he was contracting to the plants that he’s since gotten rich enough to buy). that ran on TV. Cynical me thinx he had better “sugar daddies” backing him than SN, Widmer, & others who have nearly national distribution. Tastewise, I much prefer SN Pale Ale or Anchor Steam to Boston Lager; I get PO’d in CA airport bars that serve Sam but no good CA craft brews.

I completely understand the complexity of making insanely mass-produced light beer, but no one HAS to respect it. It wasn’t easy for Hitler in his attempts to take over the world or to kill millions of people, but I’m not going to respect the man or the process. Just like he made the choices he did, so do these corporations. I don’t care for light, low flavor beers regardless of who makes them, but I don’t mind when smaller, independent breweries make them. It’s okay to like the style, I just would rather see people buying a light lager or blonde ale from their local brewery. Same goes for any other product that has a more local option.

Personally, the major reason I get so worked-up or angry about something surrounding a MillerCoors or Anheuser-Busch is the corporate entity that they are. As more people buy into them and their products, we shoot ourselves in the foot economically as a whole by killing off small production businesses. Then there are the higher profit-driven decisions those companies make regarding labor, materials or production. Luckily with brewing, it doesn’t make sense any way you look at it to have just one enormous consolidated production facility for national and international distribution or importing most raw materials.

For those concerned about calories, just reduce them elsewhere or exercise.

My lack of “respect” comes down to a simple fact. You can make tasty low cal/low abv beer. Clausthaler, an NA, proves that. I believe it’s the hops. There’s so much that can go into brewing and fermenting that produces interesting, unique, flavor without more calories, even high carbs… but most “brewers” of lite/light and low carb beer mostly eschew that for the cheapest, most taste-less way to produce a mass amount of cheap to brew, more profit for them, product.

IMO it all goes back to the cynic attitude that motivated the industry before craft beer started to nudge the industry elsewhere. In the 60s and 70s we had the same product, with very few variations or exceptions, and branding wasall that seemed to matter when in came to selling their product. Oh, and whether you wanted DMS (corn), diacetyl (butter-like) or rice (odd, vague, but not the best example of Sake, like notes) in your beer.

Added note: I can think of a LOT of “beer” that would be VERY hard to “brew” that no one in their right mind should respect, or even like. So “hard to make” can be respected, yes, but beyond the point.