Today is the birthday of August Schell (February 15, 1828-September 20, 1891). He was born in Durbach, Germany, in the Black Forest, but when he was twenty booked passage to New Orleans. He then made his way to Cincinnati, where he married, and when he was 28, in 1856, he moved his family to New Ulm, Minnesota. In 1860, Schell formed a partnership with brewer Jacob Bernhardt, and they founded the August Schell Brewing Co. Schell’s Brewery is still in business today, and is still owned by the family who started it. “It is the second oldest family-owned brewery in America (after D. G. Yuengling & Son) and became the oldest and largest brewery in Minnesota when the company bought the Grain Belt rights in 2002.”

Here’s a biography from Find-a-Grave, which they state was taken “from the Schells Brewery site,” but it must have been from a previous version of the company website:

August Schell was born in 1828 in Durbach, Germany, located in the heart of the famous German “Schwarzwald,” otherwise known as the Black Forest region. August received an early education as a machinist/engineer but after a short time, became intrigued by the opportunities overseas. In 1848, August bid farewell to his mother and father, leaving his homeland in search of success in the United States.

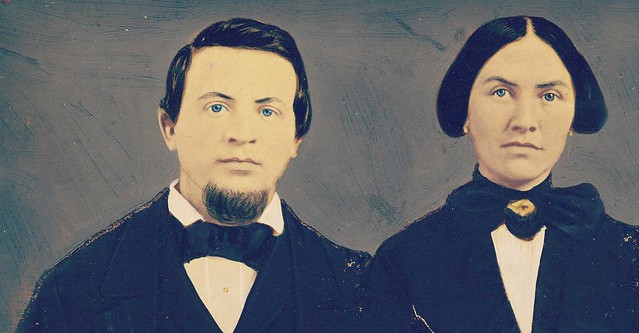

August arrived in New Orleans and continued up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers to Cincinnati where he worked as a machinist in a locomotive factory. It was here that he met the love of his life, Theresa Hermann. Theresa, also a German immigrant, and August wed in 1853.

In 1856, August, Theresa and their two baby daughters headed to Minnesota along with a group of fellow Germans known as the Cincinnati Turner Society. The Turner Society had heard from a group of German settlers in Southern Minnesota that their settlement was struggling to succeed. The two groups merged and formed the town of New Ulm.

Once in New Ulm, August found a job as a machinist in a flour mill. But as the years passed, August realized that good German beer was difficult to find in such a small, rural area. In the fall of 1860, August partnered up with Jacob Bernhardt, a former brewmaster at the Benzberg Brewery in St. Paul, MN (what today was known as the Minnesota Brewing Company). They erected a small brewery just two miles from town along the banks of the Cottonwood River. During their first year of operation they produced 200 barrels of beer, a very small amount based on today’s standards.

The location of the brewery was ideal. Aside from the beauty of its natural surroundings (August was especially fond of his hikes into the woods), the brewery was located next to an artesian spring, providing exceptionally pure water for brewing. Its proximity to the Cottonwood River gave the brewery a means of transporting beer and supplies, and the river also became essential to the refrigeration process. Each winter, large blocks of ice would be harvested and hauled up the hill where they would be stored in underground caves. The ice would keep the caves cool throughout the spring and early summer in order to allow proper aging and fermentation of the beer.

But along with the rewards also came the risks. New Ulm, as many settlers back then realized, was located in the heart of Dakota Indian country. In the early days of the brewery, many of the Dakota Sioux Tribe visited the brewery where Mrs. Schell often provided them with food. This goodwill proved to be a blessing for the brewery. In 1862, southern Minnesota was the focal point of the “Sioux Uprising,” otherwise known as the “Dakota Conflict.” While buildings were burned and ransacked in New Ulm and other towns in the region, the brewery remained untouched due to the kindness of the Schell family.

In 1866, Jacob Bernhardt became ill and decided to sell his share of the brewery. In order to command as high a price as possible August agreed to place the entire brewery up for sale to the highest bidder. August’s bid of $12,000 won out and he became the sole owner of the business.

The early years were good for the Schell family. August and Theresa raised six children: two sons; Adolph and Otto; and four daughters; Emma, Emelia, Anna and Augusta. The brewery flourished as additions were built to the existing brewery, many of which continue to grace the brewery grounds, a testament to the enduring legacy of Schell.

At the age of 50, August became stricken with severe arthritis which greatly affected his activities within the brewery. While still maintaining an executive role with the brewery, August handed over the management responsibilities to his eldest son Adolph and the brewing responsibilities to his youngest son Otto, who studied brewing in Germany. Soon after, Adolph moved his family to California leaving Otto and his brother-in-law George Marti to run the brewery.

In 1885, August and Theresa built the exquisite Schell Mansion on the brewery grounds, complete with formal gardens and deer park, all of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Sites. As August’s arthritis worsened, he would enjoy spending his days in the solitude of the gardens watching the constant hum and activity at the brewery.

August died on September 20, 1891 at the age of 63, leaving the brewery to Theresa with Otto as manager. While the brewery mourned the loss of its founder, Otto became its driving force. In 1902 the brewery was incorporated and Otto was elected president, his mother Theresa was elected vice-president, and his brother-in-law George became secretary-treasurer.

The 1860’s

Once in New Ulm, August found a job as a machinist in a flour mill. But as the years passed, August realized that good German beer was difficult to find in such a small, rural area. In the fall of 1860, August partnered up with Jacob Bernhardt, a former brewmaster at the Benzberg Brewery in St. Paul, MN (what today was known as the Minnesota Brewing Company). They erected a small brewery just two miles from town along the banks of the Cottonwood River. During their first year of operation they produced 200 barrels of beer, a very small amount based on today’s standards.

The location of the brewery was ideal. Aside from the beauty of its natural surroundings (August was especially fond of his hikes into the woods), the brewery was located next to an artesian spring, providing exceptionally pure water for brewing. Its proximity to the Cottonwood River gave the brewery a means of transporting beer and supplies, and the river also became essential to the refrigeration process. Each winter, large blocks of ice would be harvested and hauled up the hill where they would be stored in underground caves. The ice would keep the caves cool throughout the spring and early summer in order to allow proper aging and fermentation of the beer.

But along with the rewards also came the risks. New Ulm, as many settlers back then realized, was located in the heart of Dakota Indian country. In the early days of the brewery, many of the Dakota Sioux Tribe visited the brewery where Mrs. Schell often provided them with food. This goodwill proved to be a blessing for the brewery. In 1862, southern Minnesota was the focal point of the “Sioux Uprising,” otherwise known as the “Dakota Conflict.” While buildings were burned and ransacked in New Ulm and other towns in the region, the brewery remained untouched due to the kindness of the Schell family.

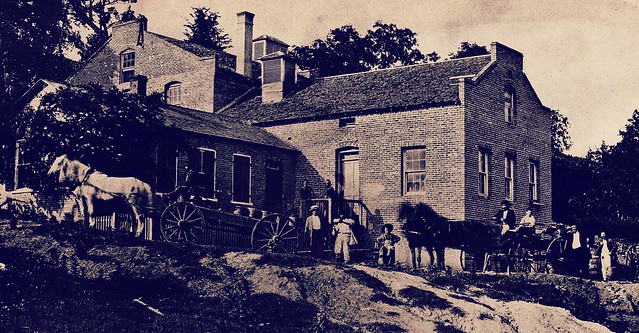

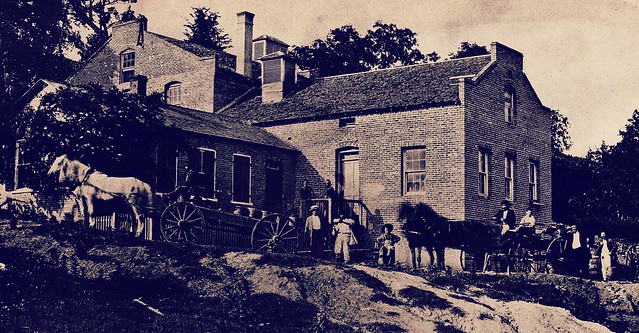

The original Schell brewery.

The 1870’s

In 1866, Jacob Bernhardt became ill and decided to sell his share of the brewery. In order to command as high a price as possible August agreed to place the entire brewery up for sale to the highest bidder. August’s bid of $12,000 won out and he became the sole owner of the business.

The early years were good for the Schell family. August and Theresa raised six children: two sons; Adolph and Otto; and four daughters; Emma, Emelia, Anna and Augusta. The brewery flourished as additions were built to the existing brewery, many of which continue to grace the brewery grounds, a testament to the enduring legacy of Schell.At the age of 50, August became stricken with severe arthritis which greatly affected his activities within the brewery. While still maintaining an executive role with the brewery, August handed over the management responsibilities to his eldest son Adolph and the brewing responsibilities to his youngest son Otto, who studied brewing in Germany. Soon after, Adolph moved his family to California leaving Otto and his brother-in-law George Marti to run the brewery.

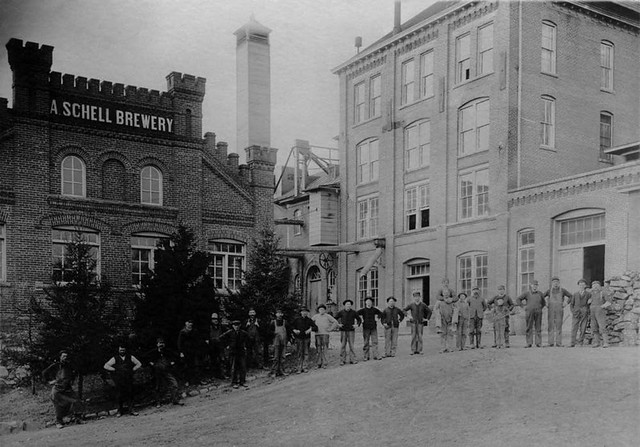

Employees of the brewery around 1866.

The 1880’s

In 1885, August and Theresa built the exquisite Schell Mansion on the brewery grounds, complete with formal gardens and deer park, all of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Sites. As August’s arthritis worsened, he would enjoy spending his days in the solitude of the gardens watching the constant hum and activity at the brewery.

August died on September 20, 1891 at the age of 63, leaving the brewery to Theresa with Otto as manager. While the brewery mourned the loss of its founder, Otto became its driving force. In 1902 the brewery was incorporated and Otto was elected president, his mother Theresa was elected vice-president, and his brother-in-law George became secretary-treasurer.

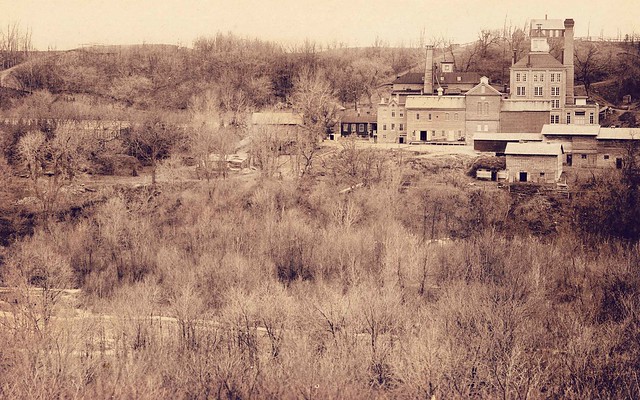

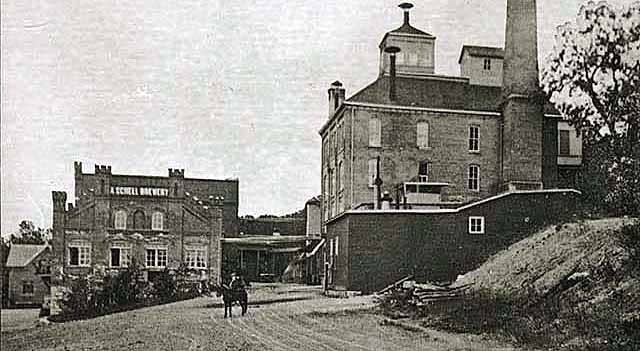

The Schell brewery seen from a distance.

And here’s an even more thorough biography from Immigrant Entrepreneurship:

Introduction

The history of August Schell (born February 15, 1828, in Durbach, Grand Duchy of Baden; died September 20, 1891, in New Ulm, Minnesota) and the brewery that he founded in 1860 highlight several key aspects of German-American business and entrepreneurship in the nineteenth century. First, it highlights the role of the Turnverein and other non-religious societies as a means of networking and organizing co-ethnic immigrants (as well as a source of potential friction within the community). Secondly, August Schell’s experiences in New Ulm, Minnesota, highlight the development of German-American entrepreneurship in small town, rural, and frontier societies. Although many German-Americans founded businesses in urban settings, others found their avenues of opportunity in the more ethnically and linguistically homogeneous communities of rural America. The rural, frontier setting of New Ulm presented Schell with different challenges than he had faced in Cincinnati, including the Dakota Uprising of 1861, drought, and tornadoes. The tight-knit community provided for a stable family network, as well as a loyal and supportive customer base. In this context and through the work of his son, Otto Schell (1862-1911), and son-in-law, George Marti (1856-1834), the August Schell Brewing Company of New Ulm, Minnesota, was able to persist through hard times (like Prohibition) to become the second-oldest family-owned brewery in the United States (second to D.G. Yuengling and Son of Potsville, Pennsylvania).

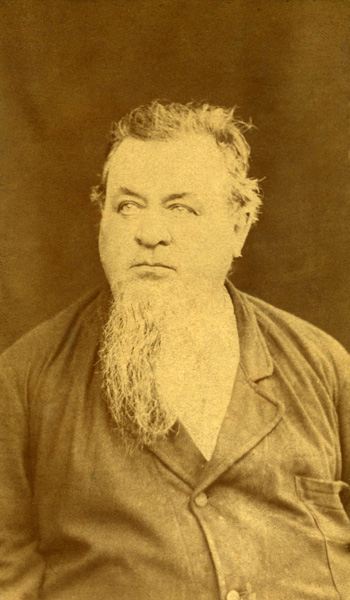

August and his wife, Theresa.

Family, Ethnic, and Turnverein Background

August Schell was born February 15, 1828, in the town of Durbach in the Grand Duchy of Baden. Situated in the rural, southwestern corner of Baden, the community was located in the foothills at the edge of the Rhine Valley and the Black Forest. Little is known about Schell’s family in the German lands outside of family stories and histories. Schell’s father, Carl Schell, who was born in 1769, was from Kippenheimweiler, Baden, a community near Durbach. According to family accounts, Schell’s family had an artistic bent having been involved in the stained-glass industry for years. But it was through a profitable marriage dowry that Carl Schell could afford to build a four-story brick house in the center of Durbach. Carl also held the position of Oberförster (head forester) in the region of the Black Forest near Durbach. As a result, Schell grew up in a world surrounded by trees and animals. The family coat-of-arms, carved into the archway of the Schell house’s caller in Durbach, depicts a jumping buck with “C Sch” inscribed above it. A love for the outdoor beauty of the Black Forest remained with August Schell and impacted how he designed his brewery, his house, and his property in order to recapture the land of his childhood. The family coat-of-arms eventually became the symbol of Schell Brewing Company.

Relatively little is known about Schell’s activities prior to immigrating to the United States. His father, Carl, died in 1839 and sometime after this he was apprenticed as a machinist prior to his decision to immigrate to the United States. Schell family remembrances indicate that he immigrated to New Orleans in 1849 but soon left for Cincinnati because the language barrier hindered his job search. With a large and growing German-speaking population in Cincinnati, Schell quickly found work as a machinist at the Cincinnati Locomotive Works. Four years after arriving in the United States, he married Theresa Hermann (born October 16, 1829; died May 21, 1911) who had emigrated from Rottweil in the Kingdom of Württemberg in 1849. After moving to New Ulm, they had five children, including the two boys who would play a role in the operation of the family brewery, Adolph (1858-1938) and Otto (1862-1911).

Although religious organizations tended to be among the strongest institutions around which German immigrants congregated, Schell did not follow this path. Schell, like many other German emigrants in the wake of the Revolutions of 1848, turned to the local Cincinnati Turnverein, founded in 1848 as the first Turner society in the United States. Although it is not known whether Schell participated in the Revolutions of 1848, he associated with the uprising’s sympathizers and refugees. More than any other network or ethnic association, Schell’s growing involvement and eventual leadership role with this German-American Turner network would have a large impact on his career and his business decisions in Cincinnati and in New Ulm, Minnesota.

The Turnverein was a liberal, gymnastic society founded amid the Napoleonic Wars. Turners believed that their countrymen needed to become stronger and more physically fit in order to unite and defend their homeland. Under Napoleon, French forces had overwhelmed the divided German states, which had been brought within the French political orbit. Despite being opposed to the French, the Turners embraced many of the liberal, Enlightenment-based notions at the root of the French Revolution. Turners were in the front ranks of the so-called Revolutions of 1848 that swept across Europe. These revolutions were fueled by the ideologies of liberalism (e.g. a constitutional monarchy or a republic with a written constitution and an elected legislature) and nationalism (combining the many Germanic kingdoms and principalities so that all Germans would live within a united nation-state). However, despite initial successes by the Turners and other revolutionaries, the conservative monarchs eventually reasserted control and turned against the liberals.

Most of these “Forty-Eighters,” as the political refugees to the United States came to be known, retained their radically liberal philosophy and put it into action when replanting the Turnverein movement in the United States. Reflecting their close connections to Freethinker societies, the Turners emphasized that moral instruction should not come from churches but from science and history. Turners were students of the Enlightenment and rationalism. Over the next several decades, the Turner societies maintained their emphasis on physical education but also began emphasizing the strengthening of the mind. They did not trust organized religion. The majority of these transplanted Turners were not latter-day Puritans who hoped to establish a “city on the hill” and eventually return to their homeland once their countrymen had seen the light. After the Forty-Eighters immigrated to the United States, the Turners became fiercely loyal to their adopted country and focused on its improvement. They strongly advocated integration into the American political and social spheres. The Turners soon thrived in the United States and, along with other exiled liberals, became leaders in many of the German communities across the United States.

Although there is no evidence that August Schell participated in the Revolutions of 1848, it is known that he closely followed the emigrant route of other political refugees and soon settled in Cincinnati, Ohio. Whether or not he was a Turner in Germany, Schell became an early member of the Cincinnati Turnverein. The majority of the founders were Forty-Eighters, many of whom were from Württemberg (the same region that Schell’s wife had emigrated from). William Pfaender was the first speaker of the Cincinnati Turnverein and would become the key figure in the founding of New Ulm, Minnesota. Schell would follow his fellow Cincinnati Turner into the territory of Minnesota to establish a safe haven to develop German culture in a more protected American context.

Relocating to safer environs became increasingly desirable for German-Americans as nativism flourished in the early 1850s. In Cincinnati, for example, the increasing numbers of German-speaking immigrants threatened to challenge the political authority of native-born Americans and their culture. As early as 1838, German citizens unsuccessfully petitioned the Cincinnati school board to adopt a German language program in its schools. German-speaking taxpayers, proclaimed German-language newspaper editorials, were paying for a public school education that offered little benefit to their own children. Couched in terms of constitutional rights, German Americans proposed that taxes from German residents should be earmarked for the instruction of German in the public schools. The German Americans successfully elected their own representatives to advocate their causes. The eventual creation of a bilingual German-English public school system illustrates the Cincinnati Germans’ growing confidence and political awareness amid the growing nativism.

In 1855, Pfaender wrote an article for the Turnverein’s national newspaper entitled “Practical Turnerism” that called for Turners across the country to pool their resources to create a joint-stock company that would buy land on the frontier and found a city to allow Turner ideas to flourish without impediment. For ten dollars a share, each stockholder would have a lot in the new city with other land being sold to establish “…mills, factories, and other nonprofit enterprises, which would accrue to the advantage of the whole….” Gaining the support of the national Turnverein organization, the Cincinnati Turners took charge of making this dream a reality.

With funding of $100,000 (roughly $2.68 million in 2011 dollars), Pfaender bought land on the banks of the Minnesota River in south-central Minnesota Territory from the Chicago Land Verein (Chicago Land Association). The Verein had originally bought the land and had given the tiny settlement its name of New Ulm. Facing financial ruin, the Chicago Land Verein agreed to be bought out by the Cincinnati Turnverein for $6,000 (roughly $161,000 in 2011 dollars). The two groups consolidated into a new joint-stock company known as the German Land Association of Minnesota. The executive committee of this association was based in Cincinnati where the bulk of the funds were located. Even before Pfaender set out by steamboat from Cincinnati to St. Paul, Minnesota, with the main group of initial Cincinnati Turners settlers in September 1856, August Schell and a few others had already made their way to the new German-American settlement on the frontier.

By the fall of 1856, several log houses, a post office, and two shops had been built around the town square. The Turners soon formed their own Turnverein chapter with August Schell elected as inaugural vice president of the society while William Pfaender became the corresponding secretary. Within the next year, this group erected their own Turner Hall that served as a community center, theater, and a space for gymnastics. Schell also served as one of the inaugural members of the New Ulm public school board. During his term of service, the school board erected a public school where subjects were taught in English and German. Schell found himself among the core leadership group of Turners on the Minnesota frontier. In this position, he had access to people and information, and played an important decision-making role that would prove crucial to his entrepreneurial success in the first decades of his business career.

Business Development

August Schell spent his first four years in New Ulm involved in the milling industry. A viable milling industry was crucial for sustaining most any community, since flour and lumber were in universal demand. Schell’s years of service as a machinist made the industry a natural fit and an avenue of opportunity. Within a year of Schell’s arrival, the German Land Association had financed the construction of the Cincinnati Globe Mill Company. The building not only had the milling stones and other equipment necessary to process grain but was also equipped with saws, lathes, and a steam engine to run them. Though the company found it hard to recoup its costs, the mill helped make New Ulm a regional center by processing hundreds of bushels of wheat, corn, and buckwheat during its first year. However, as the Cincinnati Globe Mill looked forward to its second year of operation, the firm was struggling financially. On May 27, 1858, the Globe Mill Company increased its shares by 700 in order to raise money to cover a $4,000 (roughly $113,000 in 2011 dollars) deficit for construction costs as well as to provide money to continue operations. The mill also decided to cut its prices for lumber and the cost of cutting logs in order to increase revenues. In spite of this measure, the executive committee based in Cincinnati decided it could no longer pay the millers and machinists until the mill showed a profit. Frustration against the far removed executive committee led to protests including a mock funeral for a key member of the committee.

In August 1858, the mill was reorganized in order to continue operating and satisfy the stockholders back in Cincinnati. August Schell, along with group of fifteen other prominent settlers in New Ulm, signed articles of incorporation for a new Globe Mills Company, incorporated on August 6, 1858. According to the document, “The Business and object of the Company is to manufacture Lumber and flour. The Capital Stock of the Company is thirty seven thousand five hundred dollars, the number of shares is fifteen hundred. The Capital Stock actually paid in is two hundred and sixty dollars.” This reorganization transferred the office of operation to New Ulm with a board of directors located locally instead of in distant Cincinnati. Schell invested twenty dollars for two shares in order to be one of the stockholders signing for the new company. All but two of the stockholders noted in the document were from New Ulm with the remaining two located in Cincinnati.

Despite the new arrangement, the mill, like the German Land Company, still struggled to break even. By December 1858, the German Land Company had only $7,400 remaining (out of $100,000 that it began with) and its debts continued increasing. Realizing that the Turner’s planned community in south-central Minnesota was unsustainable, the German Land Company dissolved itself in May 1859 only two years after it was created. Before disbanding, the original stockholders ceded much of their land-holdings to the city for future schools, hospitals, and other public facilities in order to ensure that the city survived.

The Land Company formed a committee to sell the Globe Mill Company, Inc. on the open market to recoup its costs. The asking price was $6,000 (roughly $167,000 in 2011 dollars) with an estimated value at between $10,000 to $20,000 dollars. Throughout the summer of 1859, the committee tried to sell the mill but finally decided to lease it until a buyer could be found. August Schell saw an opportunity. While the mill was unprofitable to own since it was burdened by outstanding debts for materials and equipment, Schell must have believed that profits could be made if he was only required to cover rent on the facility. Schell partnered with John Bellm and leased the mill at a cost of $1,540 per year for two years. Although no records exist to gauge how much money Schell made during this period, he netted enough profit to build a new house in 1859 on the corner of Minnesota and Fifth Street, just south of town. It was a one-and-a-half-story frame house with a stone foundation and plastered walls. It had six rooms and a basement and was valued at $1,200 in 1860 (approximately $33,500 in 2011 dollars).

Though he had been a machinist from his youth in Europe through his employment in the Cincinnati Locomotive Works and his later work at the Globe Mill in New Ulm, Schell saw brewing as a more profitable line of work than milling. This is not surprising considering that German-Americans were greatly overrepresented in the brewing industry during the late nineteenth century. Schell was not the first to build a brewery in the region, which was increasingly dominated by German immigrants. The first two breweries had been established in 1858. The Koke and Heyrich Brewery, established a mile-and-a-half west of New Ulm across the Minnesota River, only lasted slightly over a year. In the same year, the first brewery within New Ulm itself was established by Andrew Betz and August Frinton near German Park in the center of town. In addition, north of downtown, Henry A. Subilia, an Italian immigrant, was building the Waraju Steam Distillery, which cost approximately $10,000 to build. It opened for business on April 6, 1861. In a cash-poor economy, Subilia, like others in the region, bartered with customers and extended credit to expand business. The Waraju distillery traded whiskey for rye, barley, corn and wood. Nevertheless, Schell knew his local market and believed that the market could support another brewery.

Schell’s first order of business was to secure land for his brewery. He purchased a large lot one-and-a-half miles south of New Ulm in the Cottonwood Valley. It was located on the bluffs above the Cottonwood River in a heavily wooded area. The Cottonwood River connected to the Minnesota River, which, in turn, provided access to the Mississippi River. According to the purchase contract, “August Schell doth hereby agree to pay the said John Fried. Ring the sum of $208, the consideration for the said premises, in the manner following: $100 in lumber and sawing at the usual prices, $75 in goods (cash articles), $25 in cash; the whole at any time before the first day of September, in the year 1861, when requested by the said John Fr. Ring, and $8 on the first day of September, 1861, in plaster laths.” With little cash money in circulation on the frontier, Schell purchased the lot with a mixture of cash and the bartering of services and materials.

The New Ulm Pioneer, a local German-language newspaper, announced in its January 16, 1861, edition that August Schell had begun construction of the brewery and anticipated that it would be finished by the fall. Through October, Schell continued leasing the Globe Mill with Bellm to help finance his new brewery. Schell intended to live at the brewery and constructed a house next to it. By August 1861, Schell had moved his family out to the brewery site and was allowing relatives, including his sister-in-law, to stay at his house in town.

At the end of October 1861, the New Ulm Pioneer announced the opening of the new brewery owned by Schell and his partner, Jacob Bernhardt. Though he understood business and machinery, Schell had no expertise as a brewer. In order to compete with the other brewery in town, he partnered with Bernhardt, a master brewer who had been employed at a brewery in St. Paul, Minnesota. Construction not yet been entirely completed on the brewery structure, but it was ready enough to begin brewing beer. Schell had opted to create a sizable brewery with a cellar large enough for future needs. Over the next year, the Schell and Bernhardt Brewery expanded its customer base at least as far as Fort Ridgley, some 20 miles away.

Graced by a thriving farming economy in the surrounding countryside, as well as streams of chain migration by German-language immigrants, the city of New Ulm grew from 800 inhabitants in 1859 to 5,403 in 1890. New Ulm’s access to the most modern transportation systems available was instrumental to the city’s growth. Early in its history, New Ulm relied upon steamboats that plied up and down the Minnesota River. This river system connected New Ulm to the Twin Cities and, by way of the Mississippi River, to the rest of the nation. Prior to the coming of the railroads, the river was the key component in the rise of New Ulm and the spread of Schell’s product.

Business came to a halt in August 1861, however, as violence engulfed New Ulm. Native Americans on the nearby Dakota reservations struck back against encroaching white settlements after Union Army troops were shifted east to fight Confederate forces in the Civil War. Moving from north to south along the Minnesota River, waves of Dakota warriors advanced on white settlements with New Ulm being a primary target. Warned of the encroaching danger, New Ulm fortified the center of town. Schell was mustered into emergency service as a fifth sergeant in the Minnesota militia. After several sorties, the Dakota warriors moved on after failing to break the German-American defenses. The parts of town not fortified and held by the New Ulm defenders, however, were burned and destroyed. The Globe Mill, Betz & Frinton Brewery, Waraju Steam Distillery, and many of the other businesses in town were burned to the ground. Schell’s frame home where his sister-in-law and other relatives were living in town was also destroyed in the fighting. Fourteen days later, August Schell, Bernhardt, and nine or ten other men returned to the brewery to find, “…the door to the brewery broken open, the window knocked in, trunks and chests open and most empty and the best article of a pair of Sioux breech cloths outside the brewery.” Another witness noted that the Dakota had, “…killed and carried off a number of chickens [105 chickens] and burned and totally destroyed other articles of personal property,” belonging to Schell and Bernhardt. In addition to the barrels of beer that were taken from the brewery during the Sioux occupation, many other barrels were destroyed at Fort Ridgley, and in private homes and saloons within the city of New Ulm that had been burned down. In all, over 104 beer barrels had been burned. Despite the destruction, it could have been worse as the main structure of the brewery remained standing.

All settlers and businesses in the area soon applied to the federal government for reimbursement. Schell and Bernhardt, too, filed depredation claims for their losses. Money that normally would have been distributed to the Native-American residents of the Dakota reservations was instead diverted to the Minnesota settlers. This was the result of a clause typical to many of the treaties written with Native Americans who had agreed to go onto reservations in the event that they broke the agreement. As a result, Schell not only received cash compensation for his loses at the brewery but also for the loss of his home in town and family possessions including shoes, socks, quilts, and so forth. Interestingly, though valued at $1,200 in 1860, Schell claimed that the loss of the house in town two years later in 1862 would require reimbursement of $2,300 in cash (approximately $53,000 in 2011 dollars). In contrast to the owners of the distillery and the other brewery in the New Ulm area that had been completely destroyed, Schell restarted his business in relatively short order with an infusion of cash from the federal government that covered not only his losses at the brewery but also provided funds for expansion. With cash reserves on hand and a largely undamaged brewery building, Schell used this competitive advantage to increase the presence of Schell beer in the regional market while his competition had to rebuild from scratch.

In 1866, Jacob Bernhardt decided to leave the partnership due to failing health. As a result, the two men decided to put the brewery up for auction as a means to dissolve the partnership. On August 3, 1866, the New Ulm Pioneer announced the auction. In the advertisement, the brewery was described in detail. By 1866, the brick brewery building dominated the property and outbuildings for other aspects of beer production were also found there. The advert noted that the brewery had a pristine water source, a large cellar with stone vaults, a copper brewing vessel, and a twenty-horsepower mill for crushing grain. As Schell’s family had been living at the brewery since before the Dakota uprising, the sale also included the family house, horse stables, and garden. The brewery’s location near the Cottonwood River was also advantageous, as the proprietors could obtain ice from the river during the winter months for use in cooling beer in the brewery cellar during the summer months. August Schell won the auction with a bid of $12,000 ($175,000 in 2011 dollars). Although it is not known how much money Schell had to pay Bernhardt as a part of the settlement, legal notice was soon published that formally dissolved the partnership between Schell and Bernhardt and the newspaper was soon carrying advertisements for “August Schell’s Beer Brewery”.

Though now in control of his own company, Schell faced new and growing competition from fellow German immigrants as new breweries formed in the wake of the Civil War. Almost two years after Frinton and Betz’s brewery had burned down during the Dakota uprising, August Frinton rebuilt the facility under his sole ownership. He completed the reconstruction process and renamed it the City Brewery (1858-1917, closed at start of Prohibition). Jacob Bender founded a brewery bearing his name near the rebuilt Globe Mill (it would remain in operation until 1911). Also in 1866, the Carl Brewery opened but only lasted a short time from 1866 until 1871. Schell’s primary competition came from John Hauenstein Brewery which opened in 1864 in partnership with Andreas Betz (who had previously been a partner with Frinton). By the 1870s, Hauenstein owned the brewery outright and the company remained in operation over one hundred years until 1969.

As no business records remain for any of these breweries, the 1870 U.S. Census’ Industrial and Manufacturing Schedule offers a rough estimate to compare the breweries’ costs and sales. Schell and Hauenstein were able to sell their barrels of beer for an average of 9 dollars per barrel. Schell and Hauenstein’s larger production capabilities and greater capital investments gave them economies of scale that were crucial for competing against other breweries. Schell was able to produce a barrel of beer at a lower cost than any other brewery in New Ulm and thus achieve a wider profit margin that his competitors. Only Hauenstein came close. These numbers clarify why Hauenstein remained Schell’s major source of competition in New Ulm and why the other breweries had a harder time competing. Schell continued to invest in larger and more efficient production processes, thus making it more difficult for these smaller breweries to make money by competing on price.

Schell and his competitors faced concerns typical for businesses of the era, but life on the edge of the prairie presented its own unique problems in the late nineteenth century. Although Schell had emerged from the Dakota War of 1862 with a competitive advantage because the other breweries in the region had been destroyed, he faced frontier hardships as his company grew. Beginning in 1873 and lasting through 1878, massive swarms of grasshoppers plagued farmers throughout the Great Plains including south-central Minnesota where New Ulm is located. While this had some impact on grain supplies needed by brewers like Schell, the swarms devastated regional farms, which lowered purchasing power within the local agricultural economy. The Minnesota state legislature created its own grasshopper committee and provided various means of relief to the farmers of the state. There is little evidence, however, that beer consumption slowed enough to significantly harm Schell Brewing Company.

Severe weather, tornadoes in particular, threatened businesses on the frontier. In the middle of July 1881, a massive tornado tore apart much of New Ulm with over $250,000 in damage ($5,670,000 in 2011 dollars). Although Schell emerged with no damage, a relatively short distance away, Hauenstein Brewery, Schell’s main competition, took a direct hit from the tornado. The tornado tore apart the large brick structure leaving it, “…a shapeless mass of ruins, nothing remaining uninjured except the cellar vaults.” The brewery’s losses totaled over $40,000 ($908,000 in 2011 dollars) including nearly all equipment and over 2,000 bushels of malt. Fortunately for John Hauenstein, over four hundred barrels of beer remained untouched in the cellar allowing him to sell his product while rebuilding. Unlike the Dakota uprising where Schell and others were able to secure generous money from the government, Hauenstein had no insurance and could not recoup any of these losses. In fact, he began brewing new beer in covered shacks. Remarkably, Hauenstein was able to recover from this devastation. He built a new plant and incorporated his business in 1900 with a capitalization of $200,000 (5.53 million dollars in 2011 dollars). Nevertheless, the tornado hampered Hauenstein’s ability to compete with Schell.

Although rivers had played a key role in the early success of New Ulm and the August Schell Brewery, in the decades after the Civil War it became apparent that railroads were going to be crucial for continued growth. By 1872, the Winona and St. Peter Railroad (later part of the Chicago and Northwestern system) established a branch line to New Ulm. This railroad tied New Ulm closer to the rest of Minnesota and the United States. The line, however, was not a direct route, by any means, to the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. In addition, without competition, the railroad charged very high rates for the branch lines. By 1897, New Ulm became part of the Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad which eliminated nearly 90 miles of extra rail travel from the trip to the Twin Cities and tied New Ulm industry to St. Louis and other southern markets as well. Although some business leaders were not persuaded that extra taxation to raise money for the railroad connection was worth the cost, Schell unequivocally favored the development. These railroads further cemented the importance of New Ulm as the regional market center for surrounding farms.

August Schell navigated the challenges of developing a rural business by strengthening family ties in the brewery’s operation. Like many small business founded by immigrants, family dynamics played a large role in the company as the children grew older. They would play a more crucial role in brewery operations as August Schell became increasingly unable to walk due to steadily worsening rheumatoid arthritis. He turned over day-to-day operations to his family in the late 1870s. The first family member to emerge within the company was Schell’s oldest son, Adolph. Adolph traveled to Chicago to learn brewing techniques and train at another brewery before coming back to New Ulm. By 1879, Adolph was directly involved in managing the company. Though August Schell initially appointed his younger son, Otto, as master brewer for the firm, by the mid-1880s he had decided that Otto was better suited than Adolph to take the reins of the company.

After attending public school in New Ulm, Otto attended business college in St. Paul and completed a business education degree at nearby Mankato Normal College. When he was nineteen years old, Otto lived for a year in his father’s German hometown while studying brewing. After returning to the U.S., he began working in the brewery’s business office. The exact reasons behind August Schell’s decision to groom his younger son as his successor are no longer known, but soon after Adolph’s brief period as brewmaster and Otto’s return to New Ulm, Adolph was shifted out of key leadership roles in the company and given a variety of other jobs. Adolph then established his own business distributing Schell beer in areas a few hours west of New Ulm, and later moved to California in 1889 to start a fruit and chicken ranch. Though newspaper reports highlighted Adolph’s desire for a better climate as the deciding factor in his move, family reports emphasized the growing enmity between the brothers. By the early 1880s, Otto Schell had taken control of the brewery’s operations. When August Schell died after becoming increasingly weakened by arthritis at the age of 63 in 1891, he had ensured that his company would continue to prosper while still remaining in family hands.

Such family politics along with the frontier challenges and his growing competition spurred August Schell and his son, Otto, to expand and innovate. By 1879, August Schell’s continuous expansion had created a massive brick brewery with several outbuildings on the bluffs of the Cottonwood River. The main brewery was 150 feet long and from 30 to 80 feet in depth. Two main copper brew kettles dominated the brewery – one with a 25-barrel capacity and the other with a 12-barrel capacity. Underneath the main floor of the brewery were seven separate stone cellars for lagering beer and malting barley. There were four ice houses capable of storing 700 tons of ice. The ice was harvested from the Cottonwood River which ran 100 feet below the brewery at the bottom of the cliff. Each block of ice would be attached to tongs and hauled by a team of horses to the cellars via a rope and pulley system.

Schell Brewing Company’s physical plant grew even more once Otto Schell took over daily operation of the company and initiated a major renovation of the brewery. In 1887, the company installed bottling equipment in order to reach broader regional markets and appeal to retailers and consumers who did not wish to purchase an entire barrel of beer at one time. The brewery kept expanding the market for its beer as railroads made transporting beer into new regions easier. For example, in 1890, the company built an ice house in St. James, Minnesota, (about 30 miles south of New Ulm) as a distribution point. In the fall of 1890, Schell erected a new two-story brick building to house beer and ice, as well as a barley storage house to take the place of an older framed building, at a cost of $7,000 for both ($179,000 in 2011 dollars). By 1891, Schell’s produced nearly 9,000 barrels of beer a year. Otto Schell proposed to more than double the brewery’s capacity so that it could produce over 20,000 barrels a year. The expansion would take the company to a production level that only a few other breweries in the state could match, even in the Twin Cities. With plenty of cash netted from doing a brisk business over the previous several years, Schell plowed the money back into the physical plant. He hired a Chicago architect to design the changes. Throughout much of the fall and winter of 1892-1893, the brewery shut down in order to complete the rebuilding effort. For approximately six weeks, new roads were built around the facility. Shell spent almost $20,000 ($510,000 in 2011 dollars) on constructing this modernized and expanded brewery. Most of the new expansion was completed just as the Panic of 1893 derailed the United States’ economic engine. Without having to rely upon loans or banks to stay solvent, however, the Schell Brewing Company weathered the Panic of 1893 remarkably well.

Otto Schell both expanded the brewery’s physical plant and invested heavily in new, expensive machinery to stay at the head of the crowded brewing industry in New Ulm. In 1895, the company again expanded by building a four-story malting house adjacent to the brewery with the intent of manufacturing malt on a commission basis. In the mid-1890s, the brewery upgraded its machinery including a new copper kettle able to produce 125 barrels of beer at a time, steel mash tubs and tanks, and other up-to-date equipment. In 1897, Otto Schell traveled to St. Louis, a city with a sizeable German-American community, to buy ice machines for better refrigeration of beer and improved ventilation. Otto Schell invented and patented a new machine and a new method for separating hops from beer in 1902. This innovation cut the costs associated with filtering the beer in half, which further increased revenue in the long term.

When Otto Schell incorporated the August Schell Brewing Company in October of 1902 at $300,000 ($8,090,000 in 2011 dollars), he established a tradition of appointing only family members to the board of directors. The original board of directors listed Otto Schell as president, Theresa Schell, his mother and the wife of founder August Schell, as vice-president, and George Marti as secretary and treasurer. When Otto Schell died at the age of 48 in 1911, George Marti, August Schell’s son-in-law, took over as president of the August Schell Brewing Company. Operation of the company has remained within the Marti family ever since.

Though August Schell Brewing Company remained a relatively small regional brewery (one among many prior to Prohibition) compared to giants such as Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz, the close ethnic ties cultivated by German immigrants and organizations in New Ulm helped the firm to maintain a distinct identity and regional appeal. Continued family connections also played a role in sustaining the August Schell Brewing Company during Prohibition when it produced root beer (1919 Root Beer) and candy to stay afloat. Considering how few breweries remained viable outside of the large corporate breweries in post-Prohibition and post-World War II America, the fact that New Ulm boasted two breweries into the 1960s is noteworthy but also reflects the regional support for local brewing operations. After over 100 years in business, Hauenstein Brewing Company, Schell’s closest and most direct competition in its marketplace, closed its doors permanently in 1969. Such persistence proved stronger in rural ethnic communities like New Ulm where linguistic ties held people closer to others like them compared to similar sized ethnic communities in larger cities.

Social Status, Networks, and Public Life

Although the Turnverein organization aided August Schell’s initial rise in Cincinnati and later New Ulm society, Schell’s growing wealth and regional prominence soon made him a respected public figure beyond his status as a Turner. By the late 1870s, August Schell could indulge in developing his interests outside of business. He spent considerable wealth to design and create a new family mansion and elaborate gardens in the 1870s. Acting the part of a respected member of society, August Schell became a patron of the arts by hiring a young, and eventually notable, artist, Anton Gag, to help in the creation of his mansion. Like his father, Schell delighted in the outdoors and everything associated with it. He continually added to his deer park, the symbol of his brewery, which eventually grew to include sixteen deer by the time of his death in 1891. Every time an animal was added to his menagerie, the newspapers reported it. For example, while there were plenty of native deer in the area, Schell imported a tame fawn from Wisconsin to inhabit his backyard. Numerous wild animals from the Upper Midwest increasingly called the Schell deer park home, including wild geese, cranes, and pheasants. Schell’s tastes in animals ran to the exotic as he got older. In 1890, the newspaper reported that Schell’s pet monkey had escaped from its cage and was only captured five days later.

As August Schell rose in public prominence, he gradually separated himself from the local Turnverein. Schell remained a member of the Turners until his mid-fifties in 1884. Neither of his sons became members of the New Ulm Turnverein (though his son-in-law, George Marti, who eventually took over the family business in the early twentieth century became a member in 1879). Even prior to 1884, though Schell may have remained a member of the Turners, he became less prominently involved in the organization. Due to rising tensions between Turners and non-Turners in the region, Schell’s actions are not surprising. Small-town, frontier societies, in particular, breed familiarity and close ties but also sharp resentments among a population where everyone was a known quantity. The stark differences in worldviews of the Catholic German-Bohemians (who formed the bulk of the working class in New Ulm) and the liberal Turners like Schell who disdained organized religion bred underlying tensions within the community. Schell and his fellow Turners dominated the public life of New Ulm for decades. Even into the 1890s, the Turners still controlled the six-member school board that set the curriculum, hired teachers, managed the land owned by the school district, and planned construction of new schools. The total removal of religion from the schools, enforced by Turner school board members, angered many citizens of New Ulm. The Turners’ outright opposition to religion was anathema to religious parents at time when elsewhere in the United States the separation of church and state was much more loosely interpreted by school boards. This strong conviction flowed naturally out of their freethinking, liberal philosophy. Education, they believed, was the best means to combat the mysticism and superstitions bred by organized religion. Controlling the public school board, the Turners stamped their liberal philosophy upon the schools’ curriculum. For example, they used German-language textbooks published by the Turners. The public schools closed for Turner holidays as well. Furthermore, the school board held their meetings at Turner Hall. Though the Turners themselves continued using German as their primary language for years to come, they insisted that English receive primary consideration in the public schools. Their children would be raised as Americans who would be comfortable in an English-speaking world. This sentiment was not embraced by all within the borders of New Ulm. The 1892 annual New Ulm school meeting during which new school board member would be elected became a referendum on Turner influence in New Ulm in all areas of public life. One of the candidates that won a seat on the board in this election was a prominent businessman, Charles Silverson, owner of the Eagle Roller Mill in New Ulm and an immigrant from Baden as well. Silverson and his allies now openly charged the Turners with manipulating the public school system and the city’s politics.

Whether intentional or not, Schell and his family were conspicuously absent among the business leaders who participated the fight over control of the public school system of New Ulm. For immigrant entrepreneurs like Schell, getting caught up in such social and political divisiveness could have had clear financial repercussions among a knowledgeable customer base with alternate choices. Although Schell held a strong market presence in south-central Minnesota, he still faced competition not just from other breweries in New Ulm but from even more distant breweries, especially with the advent of the railroad. Seeking to maintain the widest customer base, Schell likely knew he would lose market share if he, his family, or his company were perceived as part of the simmering social crisis in the region. The Schell Brewing Company, like nearly all small-town businesses, had to negotiate intensely personal tensions within the local community in order to thrive. Market share and financial success were often impacted not simply by their product alone but by public perceptions of the company and its leaders.

Although factions within New Ulm hardened their animosity towards each other, the Schell Brewing Company remained above the fray. These examples of opposition to the Turners provide a valuable window into the community during the crucial period in Schell’s company history when control was passing from August Schell to his son, Otto. Well before the conflict of the 1890s, the Schells’ had become regarded as major public figures in New Ulm and the surrounding region not because of their status as Turners but because of their beer. Without alienating their old Turner allies and connections, the Schell family withdrew from membership in the Turners just as the non-Turner population increased dramatically, which proved to be a wise business move for the firm (perhaps as forward-looking as any other decision in the company’s history). The conflict could have led to the family being branded as elitist Turners. Instead, the Schell family retained their long-developed status as widely respected businessmen.

Conclusion

In many ways, August Schell followed a path that was typical of numerous first-generation German-Americans. As a young man, Schell immigrated to the United States amid a rush of other Germans in the aftermath of the failed Revolutions of 1848. Like many of his fellow immigrants, he initially established himself in an urban American setting (Cincinnati) among fellow German immigrants. Schell took advantage immigrant organizations to ease his transition into American society, as did many others. But whereas German-Americans often found such aid within church-related organizations (Lutheran, Roman Catholic, and others), August Schell was part of a sizeable and influential minority of German-Americans who eschewed churches and found an American home within the Turner Society. It was through his association with the Turner society and its networks that Schell became one of the respected founding fathers of the city of New Ulm, Minnesota. With such connections and advantages, Schell founded the August Schell Brewing Company just years after the city itself was founded and quickly grew it into a major business in the region. Like other brewers of his era, August Schell’s entrepreneurial activity was linked to German immigrants’ overrepresentation within the American brewing industry. He produced beer for a largely German-American consumer base, especially within the largely German-speaking New Ulm region. Through his Turner connections and his civic leadership in the region, Schell and his company overcame challenges due to war, plagues, and tornadoes that undermined many of his competitors. Whereas numerous firms founded by German-American that have survived into the twenty-first century had urban roots, August Schell’s business enterprises on the Minnesota frontier provide a valuable case study regarding the long-term impact of German-American entrepreneurship prevalent in rural, nineteenth-century America.