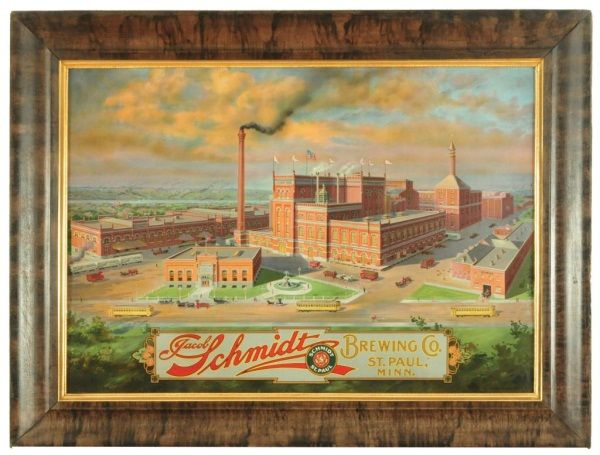

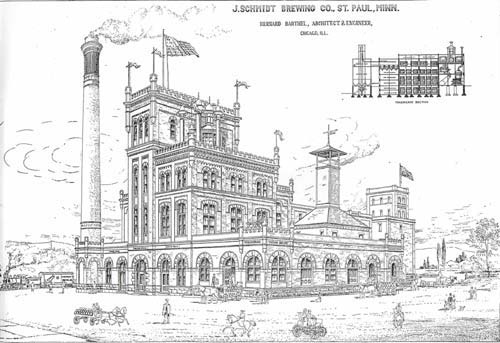

Today is the birthday of Adolf Bremer (July 24, 1869-October 9, 1939). He was born in Minnesota and married the daughter of Jacob Schmidt, who had been a brewer with Hamm’s, and others. Gremer and Schmidt partner in buying the Christopher Stahlmann Cave Brewery, and in 1900 completely remodeled it turning into the iconic “Castle” brewery with the help of Chicago brewery architect Bernard Barthel. They also renamed it the Jacob Schmidt Brewing Co., and after Prohibition, it became the nation’s seventh largest brewery, and for a time Brewer was its president. The brewery continued until 1972, when the brand was bought by G. Heileman. The Castle brewery in St. Paul was abandoned and only recently was renovated into the Schmidt Artist Lofts. Today the Schmidt Brewery brands are owned by Pabst.

Here’s a very short biography from Find-a-Grave:

Businessman. Financier and president of Jacob Schmidt Brewing Company. The son-in-law of Jacob Schmidt and the father of Edward Bremer, who was a 1934 kidnap victim of the Barker-Karpis gang.

Adolf with his son, Edward Bremer.

Here’s the brewery history from the current brand website:

In 1884, Jacob Schmidt moved to St. Paul, Minnesota and purchased a half interest in the North Star Brewery located at Commercial St. & Hudson Rd. Jacob retired in 1899, turning over the operation to his daughter and son-in-law. The following year the brewery burned to the ground and a new location was immediately found. In 1901, the brewery was incorporated as the Jacob Schmidt Brewing Company and a new plant and malt house were erected next to the existing structures.

Jacob died in 1910, but the brewery continued to enjoy success until Prohibition struck. After a failed attempt at producing soft drinks, a non-alcoholic malt beverage was created and became extremely popular.

After considerable success following the repeal of Prohibition, the company continued to prosper under the Schmidt name until 1955. Most of the original buildings still stand today, looming proudly above the Mississippi River.

Schmidt beer is known as the “Official Beer of the American Sportsman”…a slogan that capitalizes on the exciting, rugged appeal of the Pacific Northwest. The quality and brewing tradition instilled by Jacob Schmidt, continues today.

And here’s the portion of Schmidt’s Wikipedia page that deals with the brewery’s namesake:

Jacob Schmidt started his brewing career in Minnesota as the Brewmaster for the Theodore Hamm’s Brewing Co. He left this position to become owner of the North Star Brewing Co. Under Schmidt’s new leadership the small brewery would see much success and in 1899 Schimdt transferred partial ownership of his new brewery to a new corporation headed by his son in law Adolph Bremer, and Adolph’s brother Otto. This corporation would later become Bremer Bank. With the new partnership the Jacob Schmidt Brewing Company was established. In 1900 the North Star Brewery would suffer a fire that would close it for good. With the new management team in place a new brewery was needed, the new firm purchased the Stahlmann Brewery form the St. Paul Brewing Co. and immediately started construction on a new Romanesque brewery incorporating parts of Stahlmann’s original brewery along with it including the further excavation of the lagering cellars used in the fermentation process to create Schmidt’s Lager Beer.

This account is excerpted from the Land of Amber Waters: The History of Brewing in Minnesota, by Doug Hoverson:

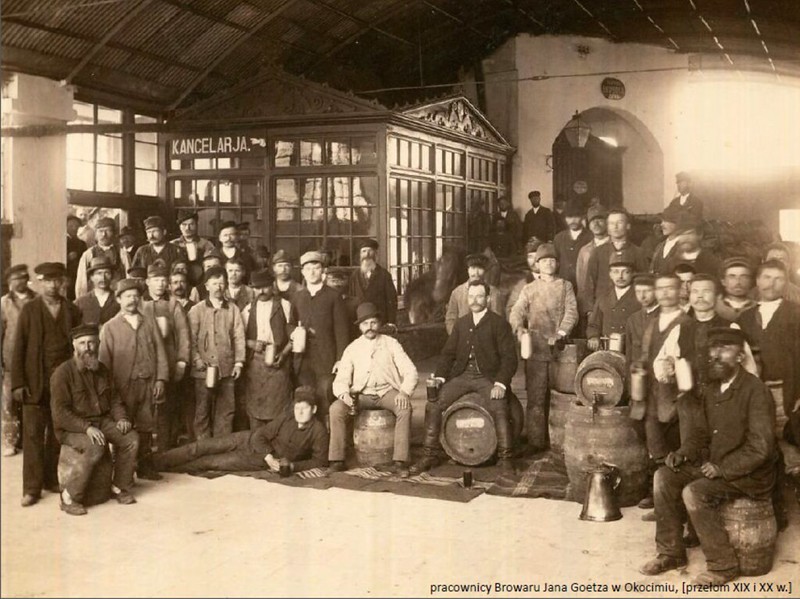

The Schmidt “Castle” brewery in 1905.

Here’s a portion of a lengthier, more thorough account of the brewery’s history, from Substreet:

He came to the United States in 1865 at the age of 20 and worked in brewhouses as he moved westward. He worked in Rochester, Chicago, and Milwaukee, before coming to Minnesota, where he found a position at Schell’s brewery in New Ulm, before moving to Minneapolis’ Heinrich’s and then to Banholzer’s and Hamm’s of St. Paul.

At Theodore Hamm’s brewery, the biggest of its kind in the state, Schmidt became not just the chief brewer, but also a personal friend of the firm’s powerful owner and namesake.

Ultimately, Jacob Schmidt wanted his own brewery.

On the other end of Swede Hollow, in 1860, Edward Drewry and George Scotten founded what would become the North Star Brewery, then just called ‘Drewry & Scotten’. Though it featured a brewhouse large enough to compete with Stahlmann’s operation on the other side of St. Paul, and had adequate—though far from extensive—underground cellars to match, this brewery produced ale, not lager beer, and therefore did not compete with Stahlmann’s brand.

After changing hands several times, it was clear by the early 1880s that North Star required a talented master brewer. The owners of that humble brewery, William Constans (grocer and brewery supply dealer) and Reinhold Koch (brewer and Civil War veteran), hired Jacob Schmidt, and the former Hamm’s brewer rapidly expanded production below the bluff.

Together, Schmidt, Constans and Koch grew North Star Brewery to the point it competed directly with Hamm’s.

In a few years, the Dayton’s Bluff brewhouse became the second greatest producer of beer west of Chicago by some estimates, sending out 16,000 barrels annually as far as Illinois. In 1884, Constans and Koch decided to leave the business, thereby leaving Schmidt as sole owner. In 1899, Schmidt took down the ‘North Star Brewery’ sign and replaced it with ‘Jacob Schmidt Brewing Company’.

The next year, it all burned.

Today, all that remains of the brewery are its aging cellars, which are a part of the new Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary in Lowertown off Commercial Street.

As he considered the cost of rebuilding, Schmidt received a proposal from St. Paul Brewing: they wanted to sell him their troubled brewery. The brewmaster accepted the offer and moved his operation into the former Cave Brewery, which had been only slightly modified since Stahlmann built it almost 50 years prior. Facilities were inadequate, but he would fix that.

Interestingly, Jacob Schmidt had all the bottles salvaged from the ruined brewery shipped to his new location. The glasses still bore the mark of the North Star brand, a large five-pointed star—a feature the brewer would ultimately opt to keep.

Stars cover the Schmidt brewery to this day, in signs and ironwork, hearkening to Jacob Schmidt’s time at, and the destruction of, North Star Brewery.

Observing the lowly state that Stahlmann’s brewery was in, Schmidt hired a rising Chicago architect, Bernard Barthel, to design a totally new complex to replace what was left of the Christopher Stahlmann Brewing Company, and St. Paul Brewing Company’s brash modifications to it.

It would be medieval on the outside, but totally modern and streamlined inside.

Soon, imposing red brick towers were rising on Fort Road, with obvious influences borrowed from feudal era castles, replacing the modest remains of Cave Brewery. Construction of Jacob Schmidt Brewing Co. was completed in 1904, followed in the next decade by its more significant outbuildings, notably ending in 1915 with the Bottling Department. Schmidt beer was some of the first to be bottled on-site in the state.

The new brewery complex was designed to compete with the biggest brewers in the country, and it did.

When Jacob died in 1911, his brewery was an icon of the West Side and the employer of more than 200 people. More importantly, the beer continued to flow, unlike the bust that followed the Stahlmanns. Though the man himself was gone, the name Schmidt was becoming ever more prominent across the country.

George and his wife Kate.

George and his wife Kate.

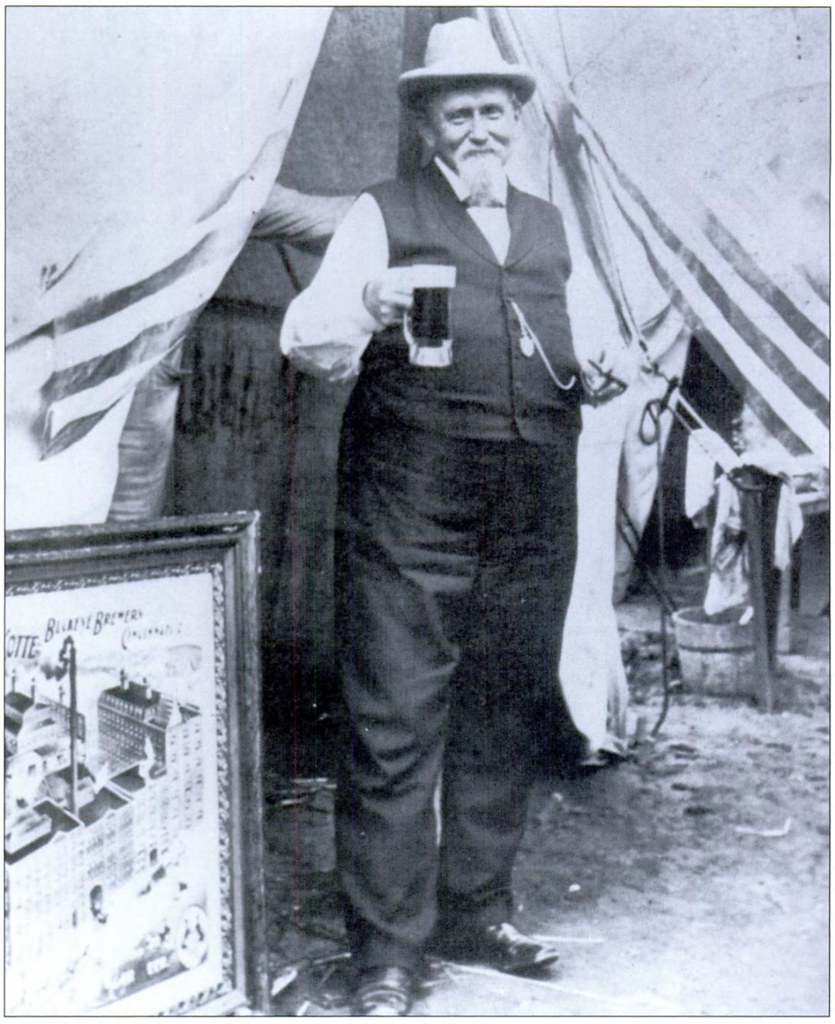

Louis Hudepohl later in life, enjoying life as a local celebrity.

Louis Hudepohl later in life, enjoying life as a local celebrity.

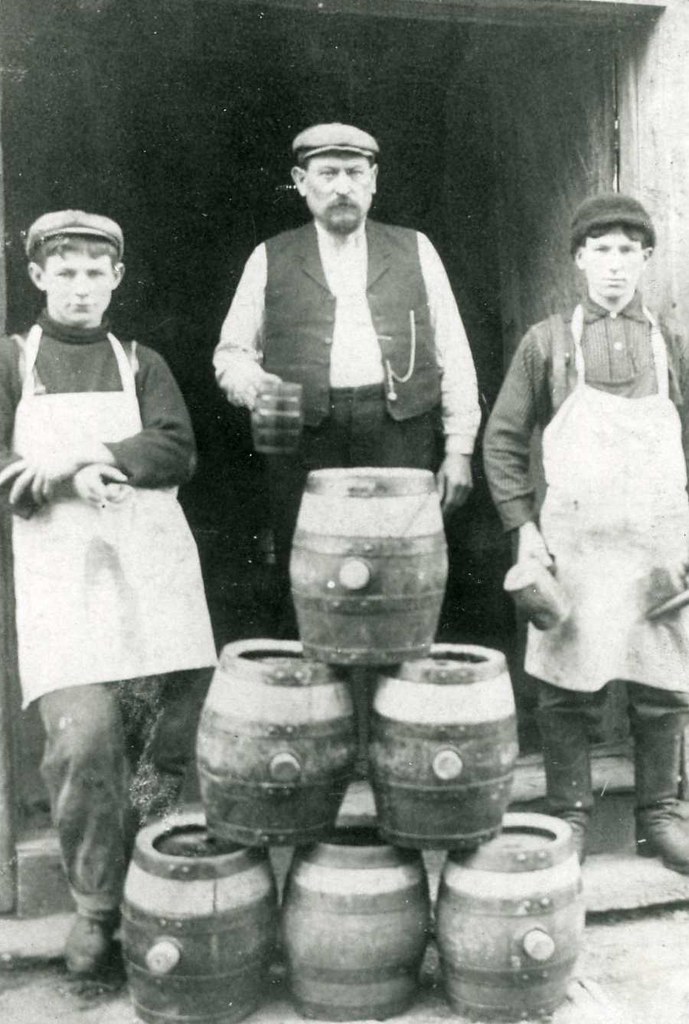

Peter Straub and two of sons, I think Anthony is on the left.

Peter Straub and two of sons, I think Anthony is on the left. The Straub Family in 1904. Anthony is in the second row, on the right.

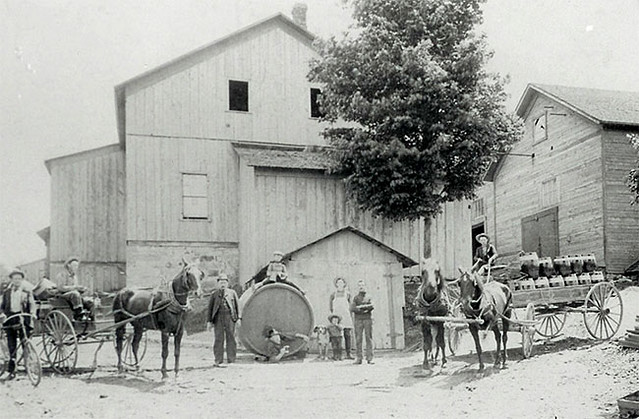

The Straub Family in 1904. Anthony is in the second row, on the right. The Benzinger Spring Brewery in 1895.

The Benzinger Spring Brewery in 1895. The family in the early 1900s. Anthony is the third from the left in the front row.

The family in the early 1900s. Anthony is the third from the left in the front row. Anthony after his first communion in the late 1800s.

Anthony after his first communion in the late 1800s.