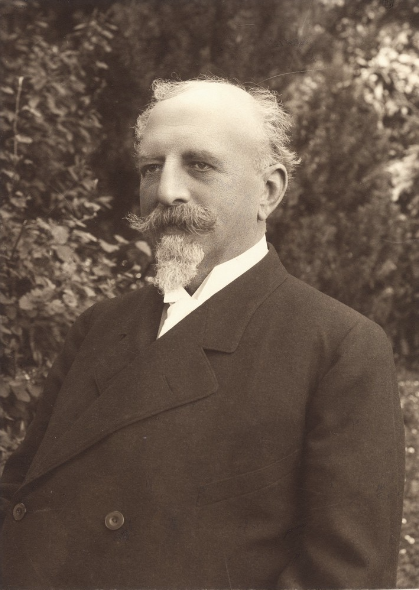

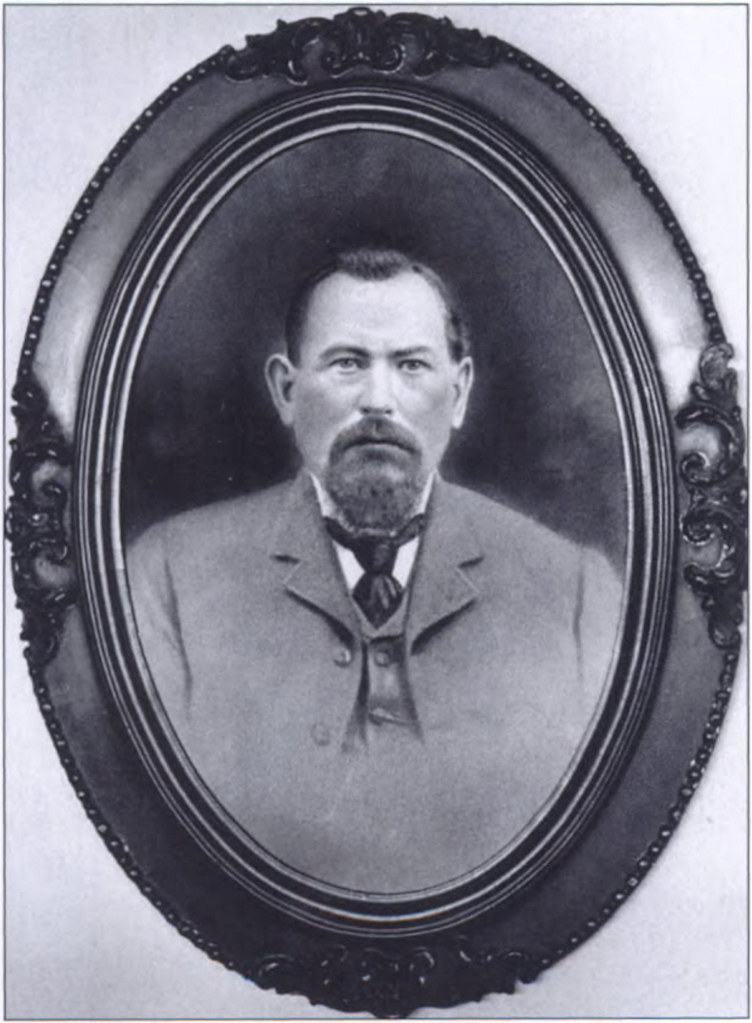

Today is the birthday of Charles F. Russert (July 24, 1861-July 8, 1920). He was born in Mannheim, Germany, the son of a brewer, and from him learned the family craft. When he was 17, in 1878, he emigrated to the U.S., originally finding work at a brewery in New York City. A few years later he became the brewmaster of A.J. Houghton & Co., which was also known as the Vienna Brewery, located in Boston, Massachusetts. He was still employed there when he passed away.

Here’s a short obituary of Russert from the Western Brewers Journal:

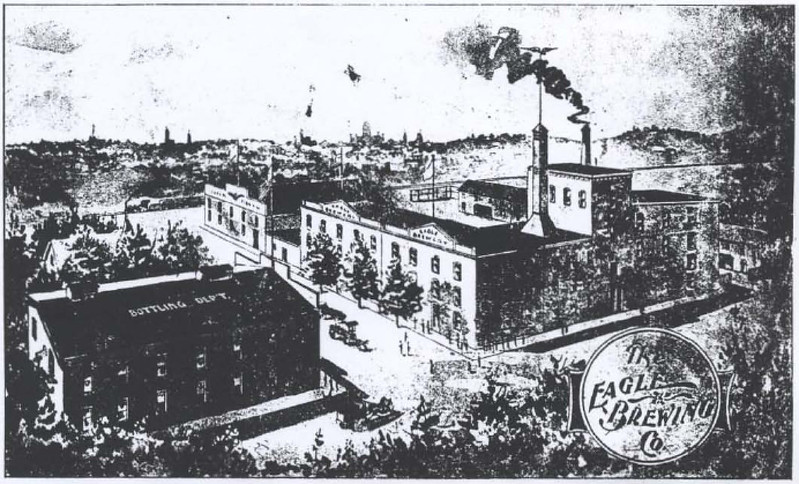

Here’s a short description of the brewery’s history from Curbed Boston:

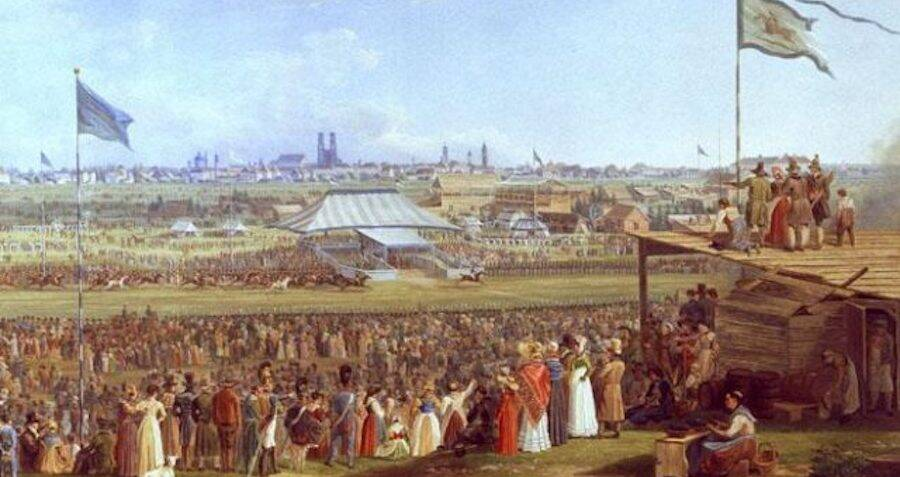

From 1870 to 1918, the “Vienna” brewery churned. It took over the site of the old Christian Jutz brewery, built in 1857. Their Vienna lager, concocted from a German recipe, came into favor in the 1850s and ’60s and displaced the heavier English and Irish ales. This is the ONLY landmark brewery in Boston that’s protected by the Boston Landmarks Commission.

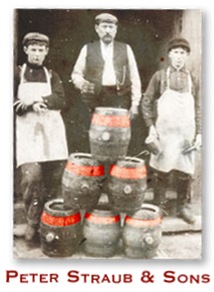

The Straub Family in 1904.

The Straub Family in 1904.

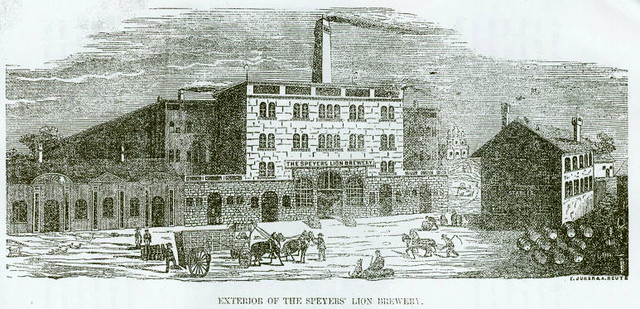

The Benzinger Spring Brewery in 1895.

The Benzinger Spring Brewery in 1895.