Wednesday’s ad is for Budweiser, from 1948. This ad features Thomas Jefferson serving up a bowl of spaghetti in the White House, and although it’s unlikely he was actually the first person to bring pasta to our shores, he did really help to popularize it. And it wasn’t spaghetti, either, but macaroni.

Here’s what Mental Floss has to say about it:

Though he probably wasn’t the first person to introduce Americans to the ooey gooey goodness of macaroni drenched with cheese, Jefferson did have a hand in popularizing it. As with ice cream, he discovered the dish while living in France and became so enamored with it that he sketched a “maccaroni” machine. He first served the delicacy at a state dinner in 1802—and back in those days, anything served at the White House became the talk of the town. People were soon clamoring for the dish, though what they ate probably didn’t much resemble today’s good ol’ Kraft.

And at the website for Monticello, they’ve reprinted this entry from the Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia:

Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Macaroni and the Macaroni Machine

In February 1789, William Short wrote to Thomas Jefferson that, at Jefferson’s request, he had procured a “mould for making maccaroni” in Naples, and had it forwarded to his mentor in Paris.1 The macaroni mold probably did not reach Paris until after Jefferson had departed. His belongings were shipped to Philadelphia in 1790, and the machine was probably included with those items. We know that Jefferson did have the machine in the United States eventually, as it is mentioned in a packing list with other household items shipped from Philadelphia to Monticello in 1793.2

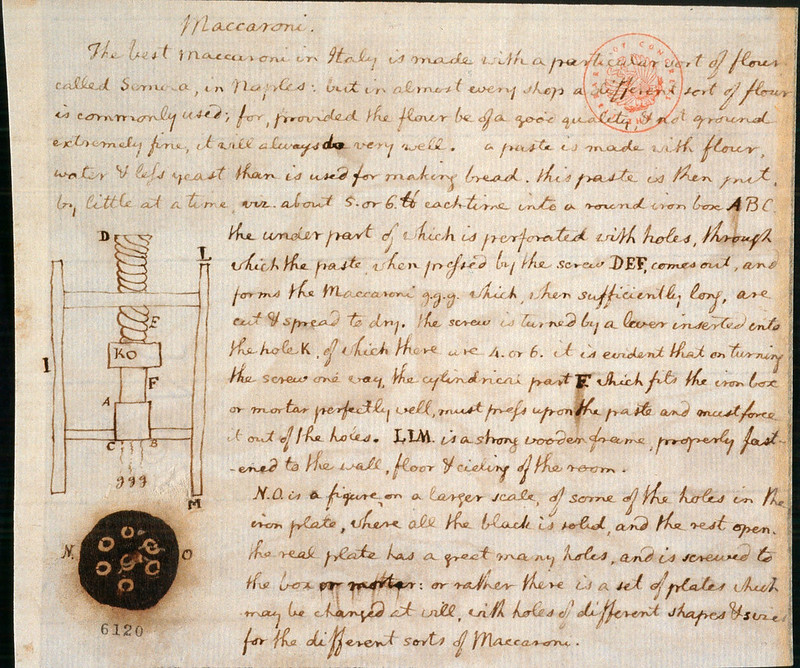

Jefferson’s notes on the macaroni machine read as follows:

The best maccaroni in Italy is made with a particular sort of flour called Semola, in Naples: but in almost every shop a different sort of flour is commonly used; for, provided the flour be of a good quality, and not ground extremely fine, it will always do very well. A paste is made with flour, water and less yeast than is used for making bread. This paste is then put, by little at a time, viz. about 5. or 6. lb. each time into a round iron box ABC, the under part of which is perforated with holes, through which the paste, when pressed by the screw DEF, comes out, and forms the Maccaroni g.g.g. which, when sufficiently long, are cut and spread to dry. The screw is turned by a lever inserted into the hole K, of which there are 4. or 6. It is evident that on turning the screw one way, the cylindrical part F. which fits the iron box or mortar perfectly well, must press upon the paste and must force it out of the holes. LLM. is a strong wooden frame, properly fastened to the wall, floor and cieling of the room.

N.O. is a figure, on a larger scale, of some of the holes in the iron plate, where all the black is solid, and the rest open. The real plate has a great many holes, and is screwed to the box or mortar: or rather there is a set of plates which may be changed at will, with holes of different shapes and sizes for the different sorts of Maccaroni.

Macaroni Recipe

Jefferson was most likely not the first to introduce macaroni (with or without cheese) to America, nor did he invent the recipe. The most that can be said is that he probably helped to popularize it by serving it to dinner guests during his presidency. There survives, however, a recipe for macaroni in Jefferson’s own hand:

6 eggs. yolks & whites.

2 wine glasses of milk

2 lb of flour

a little salt

work them together without water, and very well.

roll it then with a roller to a paper thickness

cut it into small pieces which roll again with the hand into long slips, & then cut them to a proper length.

put them into warm water a quarter of an hour.

drain them.

dress them as maccaroni.

but if they are intended for soups they are to be put in the soup & not into warm water

One diner at the White House, Rev. Manasseh Cutler, a member of the United States House of Representatives. from Ohio, wrote about his experience with it in 1802:

“Dined at the President’s – … Dinner not as elegant as when we dined before. [Among other dishes] a pie called macaroni, which appeared to be a rich crust filled with the strillions of onions, or shallots, which I took it to be, tasted very strong, and not agreeable. Mr. Lewis told me there were none in it; it was an Italian dish, and what appeared like onions was made of flour and butter, with a particularly strong liquor mixed with them.”