I’ve long held the belief that anti-alcohol ads that attempt to stop people from drinking by trying to make them feel guilty are ineffective. Pointing out the harm that such people may cause to themselves or others never seemed like the right way to encourage responsible behavior. Many, if not most, people who abuse alcohol, or any other substance, usually do so for some underlying reason. Attacking the result and not the cause always seemed like the wrong approach, like blaming the gun instead of the person who pulled the trigger. It turns out my intuition may have been correct after all.

A study soon to be published in the April edition of the Journal of Marketing Research appears to confirm that. The article, Emotional Compatibility and the Effectiveness of Antidrinking Messages: A Defensive Processing Perspective on Shame and Guilt by Nidhi Agrawal and Adam Duhachek, is based on research conducted at the University of Indiana. Their research revealed that not only do such guilt-ridden ads not work, but they actually exacerbate the problem, making it worse.

According to IU researcher Duhachek:

“The public health and marketing communities expend considerable effort and capital on these campaigns but have long suspected they were less effective than hoped,” said Adam Duhachek, a marketing professor and co-author of the study. “But the situation is worse than wasted money or effort. These ads ultimately may do more harm than good because they have the potential to spur more of the behavior they’re trying to prevent.”

That’s right folks, the neo-prohibitionist groups that have been trying to guilt people into not drinking have actually been making people drink more, perhaps causing more harm than if they’d just shut up and let people live their lives.

Here’s more about the study from a recent press release from the Indiana University Newsroom:

Duhachek’s research specifically explores anti-drinking ads that link to the many possible adverse results of alcohol abuse, such as blackouts and car accidents, while eliciting feelings of shame and guilt. Findings show such messages are too difficult to process among viewers already experiencing these emotions — for example, those who already have alcohol-related transgressions.

To cope, they adopt a defensive mindset that allows them to underestimate their susceptibility to the consequences highlighted in the ads; that is, that the consequences happen only to “other people.” The result is they engage in greater amounts of irresponsible drinking, according to respondents.

“Advertisements are capable of bringing forth feelings so unpleasant that we’re compelled to eliminate them by whatever means possible,” said Duhachek. “This motivation is sufficiently strong to convince us we’re immune to certain risks.”

So essentially, the ads trigger a defense mechanism that causes people “to believe that bad things related to drinking can only happen to others and can actually increase irresponsible drinking.”

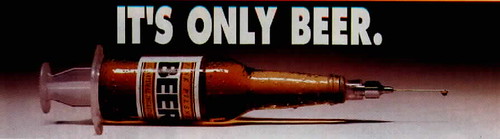

An anti-alcohol group’s PSA equating beer with heroin. It was never funny, and I always found it offensive, but it turns out it may have even driven people to drink more. You can also see more of the ads the researchers used for their study at the Media Awareness Network.

Even though the study won’t be published until next month, you can read an advance pdf of it at the Advance Articles page of the Journal (it’s the sixth one from the top). The study is 32-pages long, with another 10 pages of bibliography and other supporting data.

While the study stops short of suggesting that such ads have over time made teens and other target demographics drink more, they do caution that future ads seeking to curb dangerous behaviors employing “guilt and shame appeals should be used cautiously.” Essentially, they politely suggest that the anti-alcohol community think about what they’re doing and the consequences of ad campaigns that do not include a well-planned media strategy. What I wonder is whether or not the groups responsible for such ads will feel any guilt themselves for driving people to drink more.

UPDATE: Advertising Age had another story about this study, but from the perspective of the journal article’s other author, Nidhi Agrawal, from the Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

I’m reminded of the recent ONDCP anti-marijuana ads that did everything from making fun of couch-bound stoners to suggesting that pot will cause people to shoot each other, let babies drown and run over little kids.

The ads took essentially the most outlandish, unlikely scenarios imaginable and trotted them out as probable outcomes of marijuana use.

Not only would I bet that experienced marijuana users would simply scoff at these ads, but it’s easy for them to call the ONDCP’s bluff by affirming that the tragedies depicted in the ads basically never result from smoking pot. Thus, the message loses all its impact and users are able to rationalize continued, if not elevated, levels of use because the warnings in the ads do not seem realistic.

Similarly, you have the recent national TV ads that feature drunk people driving around cars filled with beer and cocktails that close with the stern admonishment “If you drive drunk, you WILL be caught.” Unfortunately, most people know that the risk of getting pulled over when driving while intoxicated is actually fairly low, so the ad makes a threat it cannot follow through on, and audiences know this.

I’ll be hunting down this research paper with vigor! Its reasonable that individuals who suffer from alcoholism and alcohol dependency might react negatively to ads that employ a consumption terrorism approach. I think, however, for the vast majority of social drinkers, they remain a nuisance that are given little consideration. And, it is the majority of social drinkers that create the drinking and driving problem. In fact, well over 70% of drivers who receive DUIs are first time offenders. So, if a little research will help the way we market social change, I’m all for it. I for one think we should approach alcohol consumption from the “informed drinker” perspective. You know, as a social drinker we all use tools to help us know what our BAC is when we drink so we don’t make stupid decisions. We have a speedometer in our car to measure speed and make a conscious decision whether we’re going to break the law or not. Easy. Why don’t we do the same with alcohol? I purchased a forensic-quality software application called BAQ Tracker Mobile (go to http://www.baqtracker.com or BlackBerry’s App World) and use it every time I go out socializing with friends to make sure I really am ok to drive. I love it and have been spreading the word ever since I bought it!