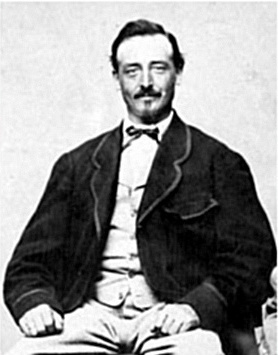

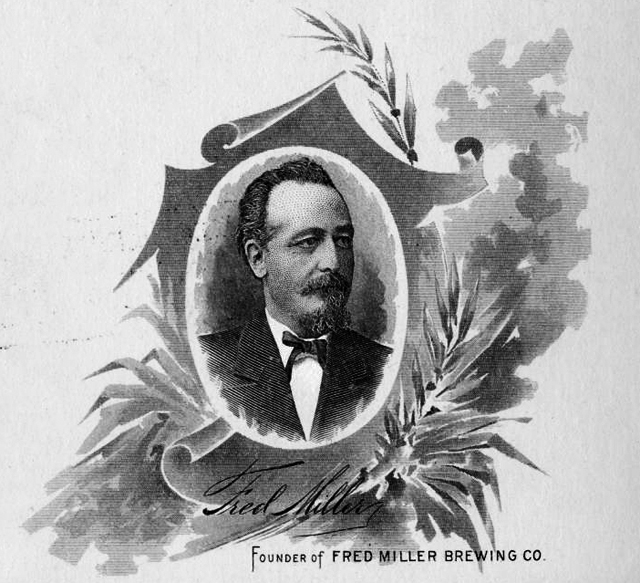

Today is the birthday of Frederick Edward John Miller (November 24, 1824-May 11, 1888). He was originally born as Friedrich Eduard Johannes Müller in Württemberg, Germany. He learned the brewing business in Germany at Sigmaringen, and moved the U.S. to found the Miller Brewing Company by buying the Plank Road Brewery in 1855, when he was 31. For a time it was known as the Fred Miller Brewing Co., but later dropped Fred’s name to become the Miller Brewing Co.

Born in Germany in 1824, Frederick Miller learned the art of brewing from his uncle in France. After working through the ranks of his uncle’s brewery, Miller leased the royal Hohenzollern brewery at Sigmaringen, Germany, and brewed beer under a royal license until political unrest caused him to emigrate to the United States in 1854. Miller arrived in Milwaukee in 1855 and purchased the Plank-Road Brewery, located several miles west of the city. Miller led the company for thirty-five years, pursuing a policy of aggressive expansion and modernization. After his death in 1888, Miller’s sons took over management of the company.

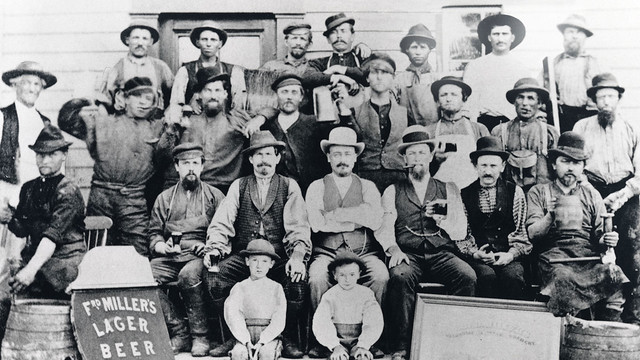

The Plank Road Brewery around 1870.

Here’s his obituary, from the Archdiocese of Milwaukee Catholic Cemeteries:

Miller, Fredrick Edward John, November 24, 1824 – June 11,1888, Began Miller Brewing Company in Milwaukee, WI, the second largest brewer in the United States. Fredrick Miller came from a family composed of German politicians, scholars and business owners. He began to learn the craft of brewing beer in Germany. At the age of 14, Miller was sent to France for seven years to study Latin, French and English. While residing in Europe, he visited his uncle in Nancy, France. His uncle was a brewer and Fredrick Miller decided to continue to learn the business of brewing.

Fredrick Miller came to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1855. He brought his passion for beer and business expertise with him. With $8,000 in gold from Germany, Miller opened the Plank Road Brewery, a brewery originally started by Fredrick Charles Best that was abandoned in 1854.Fredrick Miller was married to Josephine Miller on June 7, 1853, before they immigrated to America. Josephine and Fredrick Miller had six children together. Most of the children died during infancy. In April 1860, Josephine died. She left Fredrick with 2-year-old daughter, Louisa. When Louisa was 16, she too died of tuberculosis.

Miller was remarried in 1860 to Lisette Gross and they had several children who also died during infancy and five who survived: Ernst, Emil, Fred, Clara and Elise.

When Fredrick Miller brewed his first barrel of beer in America, he spoke passionately about “Quality, Uncompromising and Unchanging.” It was his slogan, mission and vision for the company. His statement and vision still lives on today.

Through the Great Depression, Prohibition, and two World Wars, Miller Brewing Company has preserved and grown.

Fredrick Miller died of cancer on June 11, 1888; interment in Cavalry Cemetery, Wauwatosa, WI.

This account of the early Miller brewery is from Encyclopedia.com:

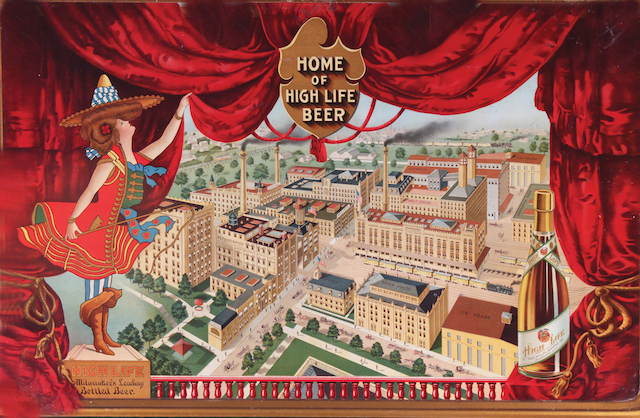

Between the establishment of the Miller Brewing Company in 1855 and the death of its founder in 1888, the firm’s annual productive capacity increased from 300 barrels to 80,000 barrels of beer. This impressive growth has continued to the present day: Miller now operates six breweries, five can manufacturing plants, four distributorships, a glass bottle production facility, a label and fiberboard factory, and numerous gas wells. Beginning with a staff of 25, Miller now employs about 9,500 people. The company currently produces more than 40 million barrels of beer per year and is the second largest brewery in the United States.

The founder of the Miller Brewing Company, Frederick Miller, was born in Germany in 1824. As a young man he worked in the Royal Brewing Company at Sigmaringen, Hohenzollern. In 1850, at the age of 26, he emigrated to the United States. Miller wanted to start his own brewery and regarded Milwaukee as the most promising site, probably because of the large number of beer-drinking Germans living there.

In 1855 Miller bought the Plank Road Brewery from Charles Lorenz Best and his father. These two men had been slow to modernize their operation, but Miller’s innovative techniques made him successful, indeed famous, in the brewing industry. The Bests had started a “cave-system” which provided storage for beer in a cool undisturbed place for several months after brewing. Yet these caves were small and in poor condition. Miller improved upon the Best’s system: his caves were built of brick, totaled 600 feet of tunnel, and had a capacity of 12,000 barrels. Miller used these until 1906 when, due to the company’s expansion and the availability of more modern technology, refrigerator facilities were built.

After his death, Miller’s sons Ernest, Emil, and Frederick A., along with their brother-in-law Carl, assumed control of the operation which was incorporated as the Frederick Miller Brewing Company. By 1919 production had increased to 500,000 barrels, but it was halted shortly thereafter by the enactment of Prohibition. The company managed to survive by producing cereal beverages, soft drinks, and malt-related products.

Finally, this account is from a brochure prepared by the Communications Department, Corporate Affairs Division, Miller Brewing Co., in the Fall of 1991:

When Frederick Miller brewed his first barrel of beer in America in 1855, he spoke empassionately about “Quality, Uncompromising and Unchanging.” It became his slogan, his vision, his mission for the company. The statement lived then as now in the dedicated commitment of employees.

Miller did more than speak his vision. He lived it. Both in the way he operated his business and in the way he handled his personal triumphs and tragedies, Miller was steadfast in his zeal for true excellence.

A glimpse into the life of Frederick Miller is presented in this brief history, which also includes some highlights of the company over the years. While this presentation is by no means comprehensive, it provides a good overview of the founder’s life and the heritage of the Miller Brewing Company.

He dressed and acted like a Frenchman, but his “confoundedly good glass of beer” won the respect of the German community of early Milwaukee. Tall and spare, Frederick Edward John Miller had a long face with a high forehead and short, Parisian beard. Born November 24, 1824, the man destined to found the Miler Brewing Company hailed from a family of German politicians, scholars and business owners and reportedly received $3,000 annually from an ancestral estate in Riedlingen, Germany.

At the age of 14, he was sent to France for seven years of study, including Latin, French and English. After his graduation, he toured France, Italy, Switzerland and Algiers. On his way back to Germany, he visited his uncle — a brewer — in Nancy, France. He decided to stay and learn the business.

Working through the various departments of his uncle’s brewery, and supplementing the experience thus gained with the fruits of observation during visits to various beer-producing cities of Germany, he leased the royal brewery (of the Hohenzollerns) at Sigmaringen, Germany,” according to the 1914 edition of the Evening Wisconsin Newspaper Reference Book. Miller brewed beer under a royal license that read, “By gracious permission of his highness.”

On June 7, 1853, he married Josephine Miller at Friedrichshafen. About a year later, their first son, Joseph Edward, was born. In 1854, with Germany in the throes of political unrest and growing restrictions, the Millers and their infant son emigrated to the United States. They brought with them $9,000 in gold — believed to be partially gifts from Miller’s mother and his wife’s dowry, but “mostly from the fruits of his own labor,” a 1955 research account indicated. An undocumented story said the money was from a royal gift, but the 1955 researcher deemed that account unlikely because of the lack of records to prove it.

After spending a year based in New York City and inspecting various parts of the country by river and lake steamer, Miller traveled up the Mississippi to Prairie du Chien and traveled overland to Milwaukee. According to another old tale, Miller slept on a sack of meal on deck while waiting for a berth to open on the riverboat.

“He found out in the morning that the place had been vacated by a man who had just died of cholera. Miller rushed to the steward, got a bottle of whiskey and swallowed it at a single tilt. He lived in fear for a week, but he didn’t get cholera,” according to a story found in the Milwaukee County Historical Society archives. The same story said that, upon arriving in Milwaukee, Miller remarked: “A town with a magnificent harbor like that has a great future in store.”

Shortly after he arrived in Milwaukee, Frederick Miller paid $8,000 for the Plank-Road Brewery — a five-year — old brewery started by Frederick Charles Best and abandoned in 1854. Miller became a brewery owner in an era when beer sold for about $5 per barrel in the Milwaukee area and for three to five cents a glass at the city’s taverns. The Plank-Road Brewery — now the Milwaukee Brewery — was several miles west of Milwaukee in the Menomonee Valley. It proved ideal for its nearness to a good water source and to raw materials grown on surrounding farms.

Another story said that, on his first day at the plant, Miller “took a brief interlude from work and killed a black bear that had poked its nose out of the bushes across the road from the brewery.”

Because the brewery site was so far from town, Miller opened a boarding house next to the brew house for his unmarried employees. The workers ate their meals in the family house, at the top of the hill overlooking the brewery. Their annual wages ranged from $480 to $1,300, plus meals and lodging.

In an 1879 letter to relatives in Germany, Miller described the meals of the employees, who began work at 4 a.m.: “Breakfast for single men (married men eat with their families) at 6 o’clock in the morning consists of coffee and bread, beef steak or some other roasted meat, potatoes, eggs and butter. Lunch at 9 o’clock consists of a meat portion, cheese, bread and pickles. The 12 o’clock midday meal consists of soup, a choice of two meats, vegetables, cake, etc. The evening meal at 6 o’clock consists of meat, salad, eggs, tea and cakes.”

The day included a rest period from noon until 1 p.m. with work concluding at 6 p.m. Miller himself arose between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. each day during the summer to “energetically tour the brewery and write a few letters.” After a 7 a.m. breakfast of Swiss cheese with rye bread and fresh butter and a large cup of coffee with cream, Miller devoted the rest of his morning to correspondence.

He spent his afternoons attending to business outside of the office, including trips to the post office, bank, railroad office and to make purchases. He went to bed at 8 p.m. in winter and 9 p.m. in the summer.

Miller was a resourceful businessman, establishing a beautiful beer garden that attracted weekend crowds for bowling, dancing, fine lunches and old-fashioned gemuetlichkeit. “You can perceive that people in America, especially where Germans are located, also know how to live,” Miller wrote. “When one plods through the week and has dealt with all sorts of problems, one is entitled to enjoy his life on Sundays and holidays and should not complain about spending a few dollars mote or less.”

An April 24, 1857, newspaper account heralded the opening of a new beer hall by Miller on Milwaukee’s East Water Street where he dispensed “an excellent article of ‘lager’ to all thirsty visitors.”

When sales dropped during the Civil War, Miller is said to have traveled with a shipment of beer directly to St. Louis, and made deliveries himself, by horse and wagon.

In June 1884, he constructed a new brewery on two acres of land he pur chased near Bismark in the Dakota Territory. Unfortunately, the state went dry the day the brewery was to open, according to one account. However, the Dakota brewery was listed among Miller’s assets when he died of cancer in 1888.

Records do not indicate the cause of Josephine’s death in April 1860, leaving Miller to care for Louisa, age 2. One family story states that Josephine died from an influenza outbreak while on a ship traveling back to Germany for a visit. Another speculated that she might have died in childbirth. At the time of her death, Milwaukee was issuing burial certificates at a rate of about 60 to 70 per week, with deaths mostly because of cholera.

Whatever the reason, Josephine’s death, and the deaths of their children, would haunt Miller throughout his life. The couple had six children, most of whom did not survive infancy, and Louisa who died of tuberculosis at the age of 16.

Miller married Lisette Gross later in 1860, and they, too, had several chil dren who died in infancy and five who survived: Ernst, Emil, Fred, Clara and Elise.

In the 1879 letter, Miller offered a glimpse of his personal torments: “Think of me and what I had to endure – I have lost several children and a wife in the flower of their youth. I myself was at death’s door several times and still God did not foresake me. Instead I was manifestly blessed in the autumn of my life.

“Whenever I think of all of them, how they were taken away from me so quickly and unexpectedly, then I become sad and melancholy…

“In spite of all the misfortunes and fateful blows, I never lost my head. After every blow, just as a bull, I jumped back higher and higher…

“Whenever I think about it, I realize we must submit ourselves without murmur or complaint to the unexplain able wisdom of God and that such wisdom transcends human understanding.”

Miller’s children with Lisette pro vided the descen dents who, with their spouses, later led Miller Brewing Company through the purchase of most of their stock by W.R. Grace Co. in 1966. Philip Morris Inc. purchased the company in 1969 and the rest of the family’s stock in 1970.