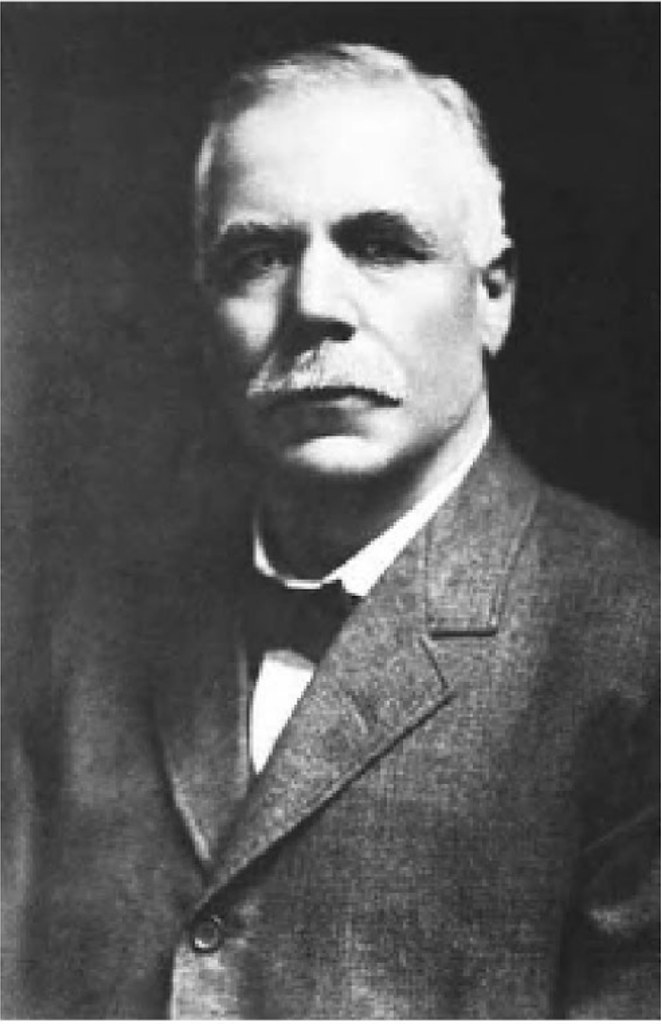

Today is the birthday of Adam Gettelman (April 27, 1847-February 14, 1925). He and his father-in-law, George Schweickhart, founded the Strohn & Reitzenstein Brewery in 1854, though the same year it became known as the Menomonee Brewery. When Schweickhart passed away in 1876, Adam Gettelman became the sole owner and renamed it the A. Gettelman Brewing Co. The Milwaukee brewery managed to remain open during prohibition and began making beer again in 1933. When Adam Gettelman died in 1925, his sons continued to run the brewery, but in 1961 was bought by rival Miller Brewing.

This short biography is from the Wisconsin Historical Society:

He began his apprenticeship in the brewing business in 1865, and in 1871 was admitted to partnership in the Menominee Brewery, owned by his father-in-law, George Schweikhart. In 1876 Gettelman became sole proprietor, and in 1887 incorporated the business, which was known as the A. Gettelman Brewing Co. after 1904. He was president and treasurer of the firm (1887-1925). His son, FREDERICK GETTELMAN, b. Wauwatosa, attended Racine College and graduated from a school for brewers, the Wahl Henius Institute, Chicago (1909). He became president of the A. Gettelman Brewing Co. on his father’s death, and was also president of the Frederick Gettelman Co., manufacturers of high-speed snow plows. Gettelman was instrumental in developing several innovations that alleviated the problems of modern brewing, including a steel barrel, a glass-lined beer storage tank, and a beer pasteurizer. He also developed a farm tillage machine.

And this an early history of the A. Gettleman Brewery, from the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee:

The A. Gettelman Brewing Company (1856-1961) was one of Milwaukee’s major industrial brewers. Although remaining a mid-sized brewer among the city’s giants, Gettelman was an important innovator of beer packaging and advertising and a significant acquisition in the expansion of the Miller Brewing Company.

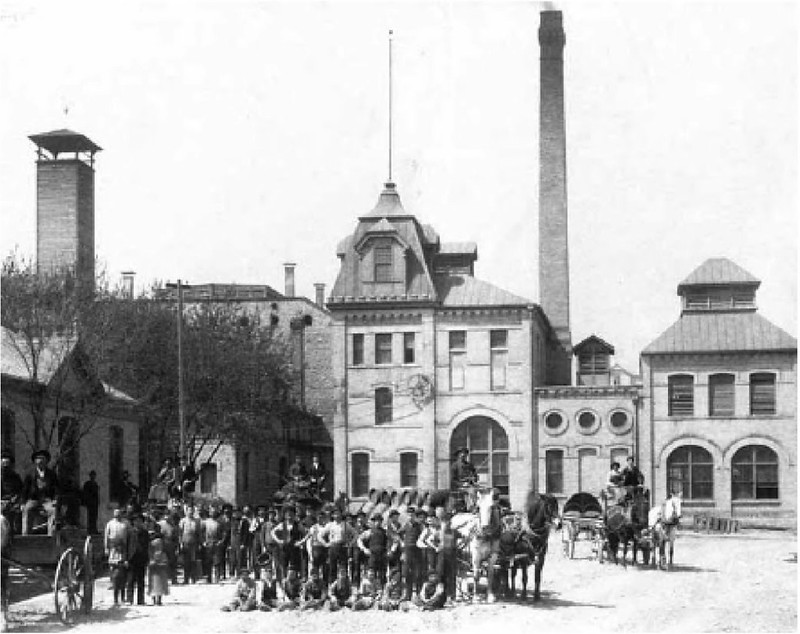

The Gettelman Brewing Company originated as George Schweickhart’s Menomonee Brewery, established near what is now 44th and State Streets in 1856. Coming from an established brewing family in Mühlhausen, Alsace, Schweickhart purchased a half-built brewery started by Strohn and Reitzenstein, who had both died in a cholera epidemic two years earlier. The brewery’s location in the Menomonee River Valley west of Milwaukee provided ideal access to clean water from nearby Wauwatosa wells, ice from the river, natural caves for storage cellars, and hops and barley from surrounding farms, while still maintaining easy access to Milwaukee and surrounding towns via the old Watertown Plank Road and later railroad connections.

In 1871, Schweickhart brought Adam Gettelman on as a partner in his brewery. Gettelman was an apprentice at the brewery who had married Schweickhart’s daughter in 1870. In 1874, Schweickhart sold off his portion to his son-in-law, Charles Schuckmann, whom Gettelman later bought out to become sole owner of the brewery in 1876. Officially named the A. Gettelman Brewing Company in 1887, the Gettelman family remained in control of the brewery for three generations, until it was sold in 1961.

Fire destroyed a significant portion of the original brewery in 1877, and Gettelman rebuilt and updated their facilities. Gettelman kept the brewery relatively small—just big enough for the family to manage and maintain a high quality product. In 1891, Gettelman introduced its flagship “$1,000 Beer” brand, offering a $1,000 reward to anyone who could prove that it was made with anything other than pure barley malt and hops. Gettelman also introduced its popular “Milwaukee’s Best” brand in 1895.

Gettelman survived Prohibition making “near beer” and through several different investments outside of brewing, like the West Side Savings Bank, the development and manufacturing of snow plows, gold-mining in the American southwest, and a sugar beet processing plant in Menomonee Falls. Gettelman returned to brewing in 1933, with Frederick “Fritz” Gettelman as president.

And this history of the brewery is from a company brochure from 1954, when the brewery was celebrating its 100th anniversary.

OBSCURE as might seem the relationship between a cholera epidemic and the origin of a brewery, no one recording the history of the A. Gettelman Brewing Co. can over-look the fact that if it had not been for the former the latter might never have existed — or, at least, not as it is known today.

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, two men known as Strohn and Reitzenstein bought a three-acre tract of land on the old Watertown Plank Road in a village west of Milwaukee then called Center City. Even in that early year, the seed of the reputation Milwaukee was to gain as the world’s beer capital was beginning to show signs of germination. The predominantly Germanic strain of its population probably had something to do with it, but the real reason was the same then as it is today — its proximity to a limitless supply of water ideally suited for brewing good beer.

There was at least one other important consideration that led the Messrs. Strohn and Reitzenstein to select the spot they did — the fact that it was close to the Menominee River from which ice might be harvested to supply the all-important refrigeration.

But, despite their canny judgment in the choice of a site for their brewery and all their plans for its construction and operation, the two men were never to see their dream materialize. Both were cut down by the cholera epidemic then ravaging the country at a time when their project had advanced no further than the excavation stage.

Meanwhile, the word that Milwaukee was an ideal spot for brewing beer had reached as far east as Buffalo, New York. One of its citizens, a brewmaster by the name of George Schweickhardt, heard it and, with his brother, made the trip west to investigate. They came across the excavation on the Watertown Plank Road. Like the men who had first chosen it, the Schweickhardt brothers knew a good spot when they saw one and it was not long before the structure which today forms part of the A. Gettelman Brewing Co. began to take shape.

The problem the Schweickhardts faced was not merely one of building their brewery and selling its product to an eagerly awaiting public. Even then competition in the beer business was keen. There were about 15 other breweries in and around Milwaukee vieing for the favor of the great Milwaukee beer palate. It was then, as it is now, a question of survival of the fittest.

In time, however, the brewing know-how George Schweickhardt had accumulated in New York and, before that, as a brewer and wine-maker in his native Alsace began to pay off. With the disappearance of the weaker of his competitors and passage of the years, it became evident that the Menominee Brewery — as it was then called — would take its rightful place in the great family of breweries that was to make Milwaukee a by-word wherever beer drinkers gather.

For anyone accustomed to highly organized metropolitan Milwaukee, the thirteenth largest city in the nation, it is difficult to imagine the rugged conditions existing when the A. Gettelman Brewing Company was in its early formative stages.

Little similarity can be found for example between State street, today one of the city’s most heavily traveled thoroughfares, and the old Watertown Plank Road which, at one time, was the brewery’s only avenue to the Milwaukee market. Perhaps no one intimately connected with the brewery remembers this state of affairs more poignantly than “Uncle” Charlie Schmidt, veteran employee and secretary of the company at the time of his retirement in 1950. “The Watertown Plank Road . . . was a dirt road subject to heavy travel by wagons hauling stone from the stone quarries nearby,” Uncle Charlie writes in his memoirs. “Extensive travel on this road resulted in six inches of fine dust in dry weather and a like amount of mud when it rained. From the Miller Brewing Co. to our plant was a walk consisting of two 12-inch planks side by side. Even so, we often had to wear rubber boots for there was still plenty of mud to walk through.”

In those days, according to Uncle Charlie, the trip from the brewery up the hill to 35th Street was a task for only the stout of heart. So arduous was the ascent, in fact, that the team of horses starting to pull a wagon loaded with 35 to 40 half barrels had to be augmented about half way up the hill by an additional team.

As though just traversing this road was not painful enough, travelers entering the city were forced to pay a fee at a toll gate located a block west of the brewery.

There Was a Bright Side

But all was not hardship for those who shared their youth with that of the A. Gettelman Brewing Company. In striding toward its destiny, a city often tramples underfoot some of its inherent natural charm. The Menominee River, now sullied by the wash from heavy industry, was once a fisherman’s dream. Just west of the brewery the river was dammed up to make a reservoir for winter ice-cutting operations. In the spring of the year, when the water was high, pike, pickerel and suckers came up the river to spawn — and to fall prey to the fishermen along its banks. What fish — particularly suckers — the farmers couldn’t eat they boiled thoroughly and used for hog-feed.As was mentioned before, protecting the beer against the extreme temperatures prevailing in this part of the country was a major problem. Refrigeration as we know it today was not even in the dream stage and the methods of keeping the beer cool in summer and warm in winter bordered on the bizarre by present day standards. About the year 1878, Gettelman had two ice house branches, one located at 14th and Highland and the other at S. 10th and Walker. Every afternoon, Gettelman’s two beer peddlers — Biegler and Hartzheim by name — would get their day’s load of beer from the brewery and haul it to the ice house assigned to their use. There they would unload it, store it overnight, and load it up the next morning to be delivered to their customers.

Tough on Country Drivers

The rigors of those handling the beer in the city was nothing however, compared to those with which the country peddlers were confronted daily. Two men, a Henry Stadler and a Bill Dienberg, covered, between them, Elm Grove, Brookfield, New Berlin, Butler, Fussville and Menomonee Falls. Though this would be considered an extremely limited area today, it took the two men a full 12-hour day to make deliveries. And this does not take into consideration the time it took them to load up in the morning, and to feed and clean their horses at night. As compensation for their efforts, each man received a cool $45 per month.Close Employee Association

But the lack of transportation facilities and personal conveniences which worked such great hardships on early brewery employees made for a close association between them which belongs only to the past. Since most of the early employees of the Menominee Brewery were single, they lived and boarded on brewery premises. A large room was provided for sleeping quarters and what is now the office reception room served as a dining area. The task of serving the men their meals fell to Mr. Schweickhardt’s daughter and a full day’s job it was. Breakfast was at 6 a.m., lunch at 9, dinner at 12 and supper at 6 p.m.As Magdelana Schweickhardt bustled around the groaning board matching the supply of good German home-cooked victuals to the hearty appetites of the boarders, she was regarded with special interest by a man whose natural leadership qualities had won for him the position of brewery foreman. As day followed day, the friendship between Magdelana Schweickhardt and her father’s foreman ripened and eventually culminated in marriage. That was in 1870 and the day was a fateful one for the Menominee Brewery for the man Magdelana married was Adam Gettelman who was later to give his name to the company as it is known today.

By the year 1870, the brewery which Strohn and Reitzenstein had begun about 18 years before had grown into a vigorous young business. The brewing lore that George Schweickhardt had learned in his former brewery at Buffalo plus the increasing demands of a robust and thirsty Milwaukee populace had put the business on a sound financial footing and made it a force to reckon with on the competitive market.

Jointly guiding its destiny until 1876 were George Schweickhardt and his son-in-law Adam Gettelman. In that year, the senior partner of the firm left the brewing business to devote his full time to a stone quarry on the Hawley Road of which he was half-owner. The move left the youthful Adam Gettelman to conduct the affairs of the brewery by himself.

The next year — 1877 — was a trying one for the new proprietor and everyone associated with the brewery. About noon of October 30 fire struck the brewery buildings and caused more than $31,000 damage before it was finally brought under control.

A good idea of the journalism of the day can be gained from the story of the catastrophe carried by the Milwaukee Sentinel the next day. It read, in part: “Yesterday noon a man rode in on horseback post-haste, over the Watertown Plank Road, to secure the services of the fire department. The brewery of Adam Gettelman & Co. in the Menominee Valley, about half a mile northwest of Fred Miller’s Brewery, had taken fire and would be reduced to ashes if the city authorities failed to honor his call for assistance. The excited rider reined in his perspiring horse before the house of No.5 and thence word was telegraphed to headquarters. ‘Fire beyond the city limits — shall we run the steamer?’ was the announcement. The code would not admit of a more satisfactory message. Chief Lippert hitched his gray horse in a twinkling and drove off as if the very Nick had taken to the road in the rear, and soon answered the telegraph in person. The steamer was ordered out, Supply Hose No. 1 was telegraphed for and with all due speed the burning buildings were reached.”

The story goes on to relate how heroically the firemen labored to save the brewery as well as the home of Mr. Schweickhardt to the south of the burning buildings and the two-story brick ice-house to the north. Concerning the fire-fighters’ valiant efforts, the article had this to say: “Engineer Dusoldt kept his steamer steadily at work, and so evenly that there was no bursting of hose to interrupt the service. All the firemen labored with a will that reflected a credit on the service and gained them the praise of all on the grounds. The steamer of the National Home had been sent for, but, owing to some misunderstanding, the veterans failed to appear. The Milwaukeeans were obliged to fight the fire alone, and right royally did they charge upon and subdue it.”

Brewery Suffers Financially

Despite the vigor with which the fire-eating stalwarts “did charge upon and subdue” the blaze it consumed enough of the Gettelman property to burn a sizable hole in the brewery’s bank account since the loss was only about half covered by insurance.Despite everything, though, a news item appearing in the Sentinel of November 3, 1877 — only a few days after the fire — stated that contracts were being let by the brewery for reconstruction.

With completion of the rebuilding program, the A. Gettelman Brewing Company continued its steady march toward popular favor. Keeping pace with the growth of the brewery was the family of Adam and Magdelana Gettelman. In 1884 a son, William, was born to them followed three years later by Fred and Elfrieda. In later years, William was to become president of the West Side Bank founded and headed until 1925 by his father. Fred stayed on with the brewery to inherit its presidency and make himself a symbol of the brewing industry in Milwaukee and everywhere Gettelman beer was consumed.

$1,000 Beer Introduced

It was Adam Gettelman, however, who started the famous “$1,000 Natural Process” on its way to the high esteem it enjoys today. In 1891, Gettelman advertising started carrying an offer of $1,000 to anyone able to prove that Gettelman’s premium beer was brewed with anything but pure malt, hops and water. This occurred in a day when the brewing industry in general was swinging to substitute ingredients. Chemists all over the country made a play for the $1,000 but, to this day, no one has ever been able to claim it.Also carrying the $1,000 reward was Gettelman’s “Hospital Tonic” introduced in 1892. Backed by the recommendation of the medical profession, the new tonic plummeted to popularity on the wings of its especial value to nursing mothers. The “Hospital Tonic” no longer graces the shelves of the nation’s drugstores — due, probably, to advent of scientifically prepared baby formulas and increased tempo of modern day existence.

Gettelman Spur Built

By the year 1895, Gettelman’s production had soared to the point where it was no longer feasible to haul the beer by wagon to the railroad situated on the shores of Lake Michigan. Accordingly, a spur from the Milwaukee Road mainline was run into the brewery yard. This was a momentous event in the life of the brewery, a milestone in its progress. It was no more than fitting, therefore, that the occasion be marked by a celebration of major proportions.And so it was. On April 13, 1895, a huge crowd gathered on the Gettelman grounds to watch Adam Gettelman drive the “golden” spike that would signal completion of the spur. While Hensler’s Juvenile Band spiritedly played “How Dry I Am” and the crowd cheered enthusiastically, Adam started pounding away at the spike. About half way through the operation, one of the on-lookers –William Starke by name — asking Adam to stop, placed a nickel on the flange of the rail so the imbedded spike might hold it there. “Here’s the nickel,” he said, “for a good glass of beer.”

As the last stroke of Adam Gettelman’s mallet was still ringing in the air, the first car was shunted into the siding. It was a beer car filled with official well-wishers from the Miller Brewing Company, two blocks away. Together, Gettelman officials, Miller officials and a hundred or so thirsty bystanders trouped into Gettelman’s bottle house to get down to some serious suds-slurping. The day was a decided success.

Lying between the turn of the century and the beginning of the Prohibition era were years of growth and development for the A. Gettelman Brewing Company. In the 50-odd years of its existence, Gettelman beer had become as much a part of the Milwaukee scene as its culinary counterpart wieners and sauerkraut — and as dear to the heart of every true Milwaukeean. In the face of an increasingly active market with that exacting taskmaster Production rapidly ascending to power, Adam Gettelman serenely guided his brewery along the path of quality brewing. While other breweries spread their supply lines to the four corners of the land, Adam was content with providing his Milwaukee friends with the kind of beer that smacked of the good old days.

Consequently, the little brewery on the old Watertown Plank Road never loomed as a Titan among others of its kind, nor does it to this day. But, in staying small, it retained the warmth and “family feeling” it had in the days when Magdelena Schweickhardt — later the bride of Adam Gettelman — served steaming hot ”vittles” to the brewery’s jovial worker-residents.

Despite the fact that the “drys” had tapped off most of the gemuetlichkeit from Gettelman’s satisfying old brew, the suds-sipping citizenry of Milwaukee remained loyal.

As if bowing out after he was assured of that fact, Adam Gettelman died in 1925. For the next four years, the affairs of the brewery were guided by Adam’s eldest son, William, who at the same time, succeeded his father as president of the West Side Bank which the latter had founded.

The cohesiveness and general esprit de corps with which Adam Gettelman, in his wisdom, had inoc ulated his company began paying real dividends with the coming of prohibition in 1919. While breweries made of blander stuff withered away under the arid provisions of the Eighteenth Amendment, Gettelman tightened its belt and turned its attention to the manufacture of “near beer” and malt syrup.

As in the case of every other brewery that lived through those trying times, Gettelman was compelled to cut back drastically on its working force. Brewmaster Julius Stemmler headed a crew consisting of Conrad Gieger, John Haertl, William Pust, William Dienberg and chief engineer Louis Gettelman. In those days, even the office force was not exempt from plant duty. It was not at all unusual for “Uncle” Charlie Schmidt, Fred Englehardt and Charlie Mollenhauer to don working clothes and pitch in when the brew reached the bottling stage. According to memoirs set down by Uncle Charlie, though, his biggest job was “to look out of the windows and count the number of automobiles passing by.”

While all this was going on, the driver’s seat of the brewery was occupied by three of the Gettelman clan — first Adam, then William, and in 1929, the rosy-cheeked Fred.

In almost every family circle there’s one child that stands apart from the others — not necessarily better or worse, but somehow different in a way that sometimes challenges description. Of all the children reared by Adam and Magdelana Gettelman in the big house on the hill overlooking the brewery, the cherubic Fritzy perhaps fitted that description more than any of the others. He shared in the heritage of good common sense handed down to him by his mother and father and their folks before them, but his had overtones of the dreamer. It was, however, flavored by a certain sharp inquisitiveness and compulsion to create that forced him to do something about his dreams rather than leave them in the air-castle stage. The same quality that caused an elastic band to appear one day on the screen doors of the Gettelman mansion so that they might shut of themselves, introduced to the beer-making world in later years the steel keg with the broad band around the middle for easy rolling. The idea for the steel keg came out of Fred’s dusty and venerable old “private engineering office” located in the building in which he had been born. It first saw light of day on a piece of “brown butcher paper,” Fred’s favorite method of putting his thoughts in tangible form. Shortly after Fred had promised exclusive manufacturing rights to L. R. Smith of the A. 0. Smith Corp., an Eastern firm offered him $1,000,000 for the same rights. But Fred had given his word and the Eastern representative went home with an unsigned contract. Manufacture of the steel barrels is now a major item on the A. 0. Smith schedule.

The spirit of not being quite satisfied with things as they were stayed with him the whole of his life. At seven Fred fitted the family baby buggy out with brakes and, with gravity as his engine, went whizzing down the decline from the house on the hill to the Watertown Plank Road far below. Much later in life he invented the Gettelman snow plow, pasteurizers for beer and milk, a washer that cleaned beer bottles with a jet of steam and a host of other things, many of which are still on brown butcher paper and will perhaps never get beyond that stage. He even played a major role in perfection of the huge glass-lined storage tanks for beer now a common sight on any brewery property.

But, though he owned as many patents as many a full-time inventor, dreaming up things to make life easier only occupied part of Fred’s time. There was a practical, everyday business side to him, too. He felt deeply his responsibility to the brewery and its employees. In a way, he had the toughest row to hoe of any of his predecessors. Not only was the brewery laboring under the yoke of prohibition, but the very year that Fred took up the reins — 1929 — the bottom fell out of things economically. There was indeed many a time during those black days that Fred’s indomitable will was the only light that pierced the darkness.

The years following repeal of Prohibition were, for Gettelman as for all of Milwaukee’s breweries, full of growth and development. The thirst of the true beer-drinker, never completely quenched by poor substitutes concocted in private cellars, sky rocketed the fortunes of the brewing industry to unprecedented heights.

But no situation, however favorable, is without its attendant dangers. With a public eager to drink anything under a brewer’s label the temptation was rife in brewing circles to cut corners on quality. Some breweries did just that and paid for their lack of foresight with extinction when the public’s first enthusiasm no longer beclouded its powers of discrimination.

Fred Gettelman, Sr., however, had piloted his brewery through the difficult days of depression and prohibition and he had no intention of jeopardizing everything he and his employees had worked so hard to preserve. Consequently, Gettelman beer, while not breaking any production records, held to the same fine quality upon which its pre-prohibition reputation had been built and the brewery came through safely.

The A. Gettelman Brewing Company first began to show signs of the new post-prohibition prosperity in 1937 with construction of an addition to the old bottle-house. An 80 x 110 foot structure, the building was twice the size of the building it annexed. Cream-colored bricks salvaged from the old Gettelman mansion atop the hill overlooking the brewery went into the construction of its walls and the bottling equipment it housed was modernity itself. In fact, Fritz Gettelman had had a hand in the improvement of the bottle washer installed in the new bottle house. It was he who had dreamed up and perfected the idea of cleaning the bottles with high pressure steam and water. So efficient was the equipment in the ultra modern bottle shop that Gettelman was able to show figures proving that breakage on bottles of all makes and ages ran only .442 per cent of total bottles handled.

In addition to the modern machinery on the ground floor the bottle shop boasted a battery of glass-lined storage tanks in the basement, an innovation which Fritz Gettelman had also helped engineer. During development of the revolutionary tanks, he had spent long hours at the A. 0. Smith plant subjecting experimental models to every conceivable torture to prove his idea that molten glass will stick to steel. How he did this in the face of skeptical college “enchineers” — as he called them –is another story, but the success he encountered is borne out by the fact that few progressive breweries today are without the big beer holders with the glazed walls.

All this while the affairs of the brewery had been directed from the office building which lies between State street and the brewery proper. By 1948, however, it was becoming increasingly apparent that the expanding brewery would need corresponding office facilities. It was decided, therefore, that an old malt-house which had, for the last several years, served as a place for miscellaneous storage be made over into an office building. Part of the building had originally been the first Gettelman homestead, antedating even the mansion on the hill. From what had once been its living room emerged the present office reception room whose walls are panelled with the cypress of the old wooden beer storage tanks. From the rest of the building the architect’s skill and a lot of hard work wrought the present Gettelman offices. Fritz Gettelman went along with, and indeed inaugurated, most of the brewery’s advances, but he turned a deaf ear to any suggestion that he move his office to the newly renovated building. Moreover, he insisted that the second story room in which he had been born and from which had come many of his ideas on the humble brown butcher paper be left inviolate — and so it has been, to this day.

Modernization of brewery and office facilities was approved by every one connected with the business, but no one sanctioned them more heartily than the two Gettelman brothers, Fred, Jr., and Tom, sons of the energetic and imaginative Fritz. Actively entering the management affairs of the brewery in 1939 and 1941, respectively, the two younger Gettelmans not only welcomed the changes but were, in large measure, responsible for their execution. Interest of the brothers in increased production and administrative efficiency was not an overnight affair. The lives of both of them had revolved around the brewery almost since they had taken their first steps and they had a working knowledge of every facet of the business long before they emerged from brewers’ school as master brewers.

As it turned out, the talents of the two men were so complementary that it seemed almost a part of some well-formulated long range plan. Fred found himself more at home in the operational end of the plant while Tom’s talents turned to the intangibles of the business — things like sales promotion, advertising and public relations.

It is in such capable hands that the destiny of the A. Gettelman Brewing Company rests. It seemed only in keeping with the spirit of Fred Gettelman, Sr. — all his life dedicated to the best interests of his business and the people in it — that, at his passing in June, 1954, he should have provided so well for his brewery’s future in the persons of his two sons.

New technological advances, widely expanded markets, an ever further propagation of the proud old Gettelman name — these are but a few of the things the two younger Gettelmans plan to make the A. Gettelman Brewing Company of the future an even better place with which to be associated than it has been in the past. To achieve these goals they look confidently to the same fine spirit of cooperation on the part of the Gettelman family of employees that has so importantly contributed to the high place the brewery now enjoys.