![]()

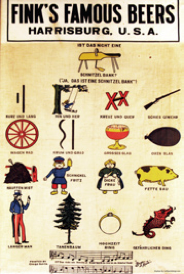

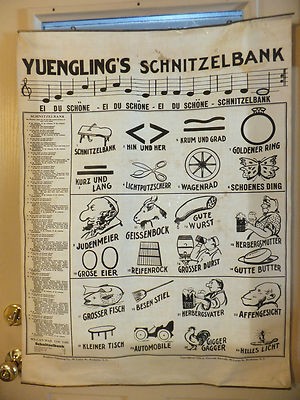

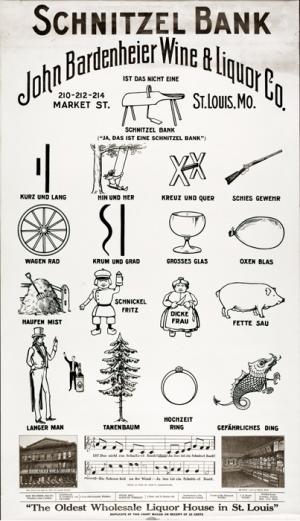

Several weeks ago, while researching the birthday of Pennsylvania brewer Henry Fink, I happened upon the advertising poster below. Intrigued, because I’m fascinated with symbols, I couldn’t make out what they were because the largest image I could find is this one. All I could figure out at the time was that it had something to do with a song.

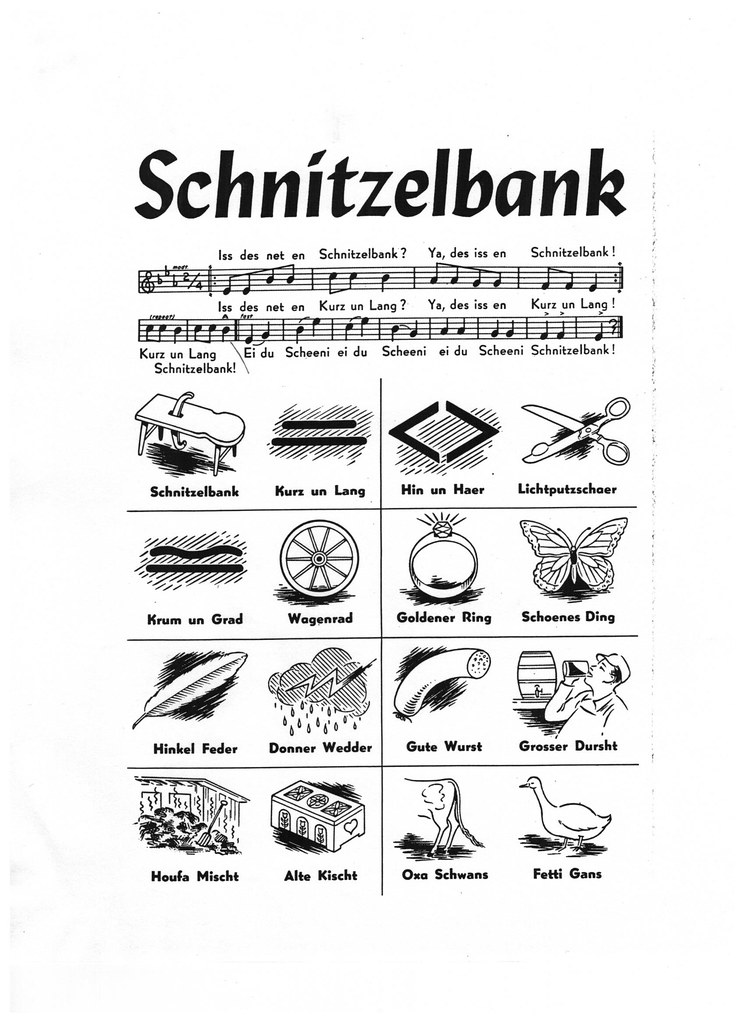

Eventually I gave up, and moved on, because if I’m not careful I’ll keep going off on tangents and down rabbit holes until I’ve gotten myself well and truly lost, not to mention wasted hours of unproductive time. But I kept coming back to it, and eventually, I had to figure out what exactly it was or go crazy. So I started taking a closer look into the poster and figured out that they’re all over the place and it’s a famous German song called the “Schnitzelbank.” And the Fink’s ad poster, or versions of it, is everywhere and has been used by breweries, restaurants and others for years. Which makes sense because, although it’s a “German-language ditty for children and popular among German Americans with an interest in learning or teaching German to their offspring,” it’s also commonly sung by adults for entertainment and nostalgia, and usually while they’re drinking beer.

In German, Schnitzelbank apparently “literally means ‘scrap bench’ or ‘chip bench’ (from Schnitzel ‘scraps / clips / cuttings (from carving)’ or the colloquial verb schnitzeln “to make scraps” or “to carve” and Bank “bench”); like the Bank, it is feminine and takes the article “die”. It is a woodworking tool used in Germany prior to the industrial revolution. It was in regular use in colonial New England, and in the Appalachian region until early in the 20th century; it is still in use by specialist artisans today. In America it is known as a shaving horse. It uses the mechanical advantage of a foot-operated lever to securely clamp the object to be carved. The shaving horse is used in combination with the drawknife or spokeshave to cut down green or seasoned wood, to accomplish jobs such as handling an ax; creating wooden rakes, hay forks, walking sticks, etc. The shaving horse was used by various trades, from farmer to basketmaker and wheelwright.”

A traditional shaving horse around 200 years old.

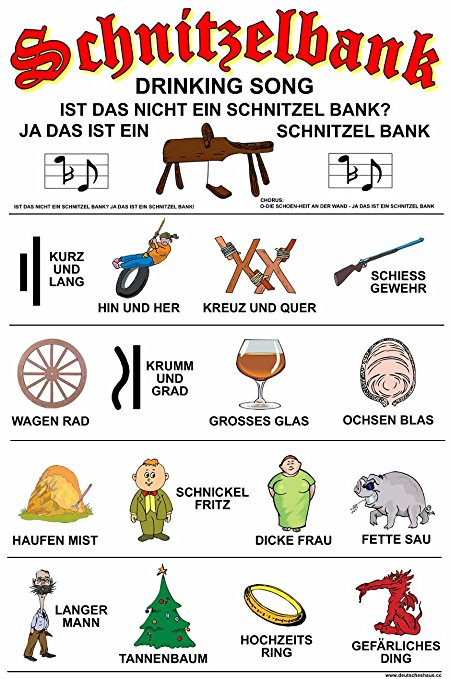

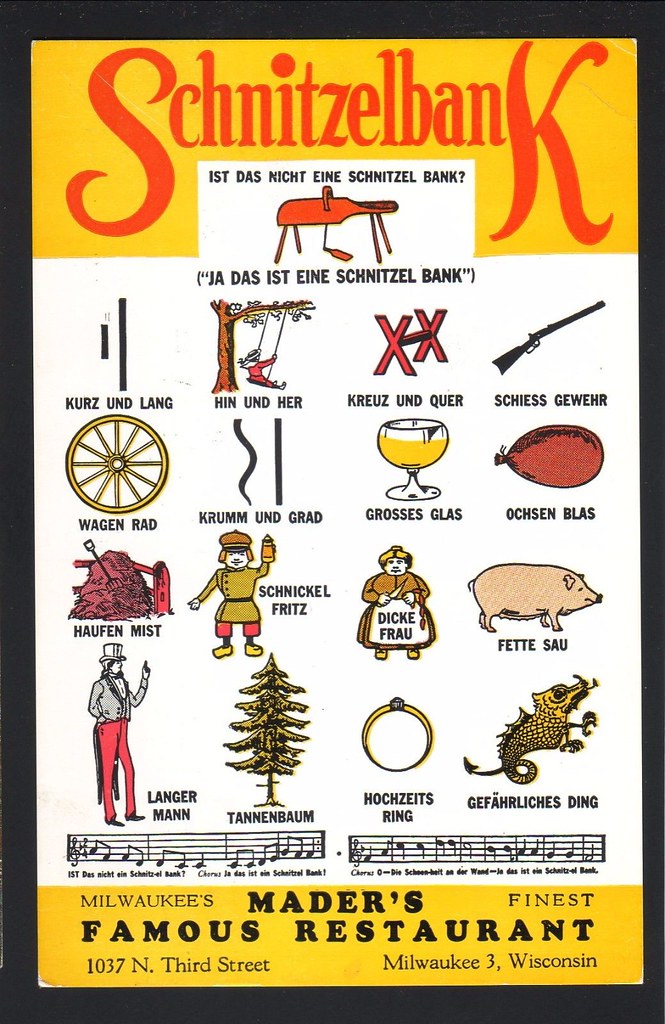

And that’s also why the posters always include a Schnitzelbank, because in addition to it being the title, it’s also how the song begins.

Here’s one description of the Schnitzelbank song:

A Schnitzelbank is also a short rhyming verse or song with humorous content, often but not always sung with instrumental accompaniment. Each verse in a Schnitzelbank introduces a topic and ends with a comedic twist. This meaning of the word is mainly used in Switzerland and southwestern Germany; it is masculine and takes the article “der”. It is a main element of the Fasnacht celebrations in the city of Basel, where it is also written Schnitzelbangg. Schnitzelbänke (pl.) are also sung at weddings and other festivities by the Schitzelbänkler, a single person or small group. Often the Schnitzelbänkler will display posters called Helgen [which is “hello” in German] during some verses that depict the topic but do not give away the joke.

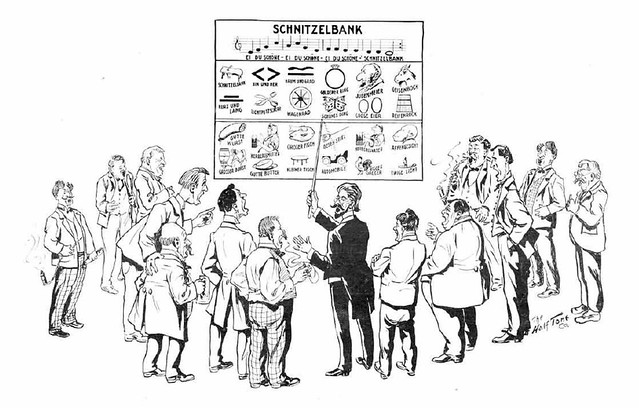

Often the songleader uses the poster to lead people in the song, pointing to the symbols as they come up in the lyrics, as this photo from the Frankenmuth Bavarian Inn Lodge illustrates.

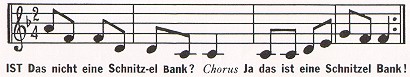

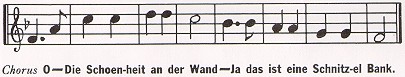

The song uses call and response, with the leader singing one lyric, and the chorus repeating it back as it goes along. So here’s what the traditional version of the song sounds like:

Some Sauerkraut with Your Schnitzelbank? has an interesting reminiscence of a visit to a Fasching Sonntag in the St. Louis area around 1982, and includes his experience taking part in the singing of the Schnitzelbank song.

In the evening, everyone moved upstairs to the parish hall, which was the typical multipurpose gymnasium with a stage at one end. Set up with long tables in parallel rows on both sides, the band in place on the stage, and the large crowd ready for the music to begin, the hall had lost its bland, bare, everyday atmosphere. On the stage, off to one side, was a large easel with a poster on it. I didn’t pay much attention to it, thinking it was for announcements later in the evening. The band started, and the dancing began in the clear space down the middle of the hall, mostly polkas and waltzes, with a few variety numbers like the dreaded Duck Dance, which explained the need for pitchers of beer. Finally, when the crowd was well exercised and well lubricated, someone approached the easel with a pointer in his hand. People started shouting “Schnitzelbank! Schnitzelbank!” The music began, and the person with the pointer called “Ist das nicht ein Schnitzelbank?” and the crowd heartily responded “Ja, das ist ein Schnitzelbank!” Then came a chorus of music, to which everyone sang, “O Die Schoenheit un der Vand, da das ist ein Schnitzelbank.” And so it continued for several verses, the person on stage pointing to another object on the poster with “Ist das nicht ein.…?” and the crowd responding at the top of their voices. I was puzzled at first, but eventually joined in and didn’t think much more about it. I’m pretty sure that only a few people knew all the German words, and that some had memorized it over the years, while the ones in front were close enough to the poster to read the words under the pictures—everyone else just shouted a cheerful approximation of what they thought their neighbor was saying.

The Schnitzelbank, or Schnitzel Bank, is a song with short verses, meant to be sung the way it was at the Fasching Sonntag, with a leader and group response. It is sung in some areas of Germany for Fasching, Fastnacht, or Karnival, and also during Oktoberfest, and other occasions where there is a happy, celebratory crowd. In America, the posters are displayed at a few German restaurants and some tourist attractions with a German American heritage, such as the Amana Colonies in Iowa and some Pennsylvania Dutch locations. Singing the Schnitzelbank in America dates at least to the turn of the 20th century, which is when the John Bardenheier Wine and Liquor Company printed its version on an advertising poster.

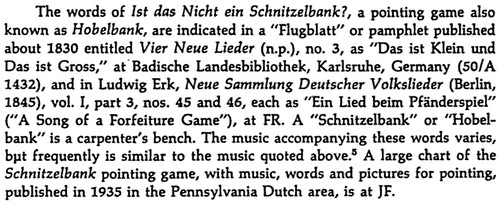

According to “The Book of World-Famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk,” first published in 1966, the melody first appeared in 1761 by a French composer and lyrics were written a few years later, n 1765, and it was known as “Ah! Vous Dirai-Je, Maman,” but it became far more well-known as “Twinkle Twinkle, Little Star” and “Baa Baa Black Sheep” in subsequent years. Apparently it first appeared as “Schnitzelbank” in 1830.

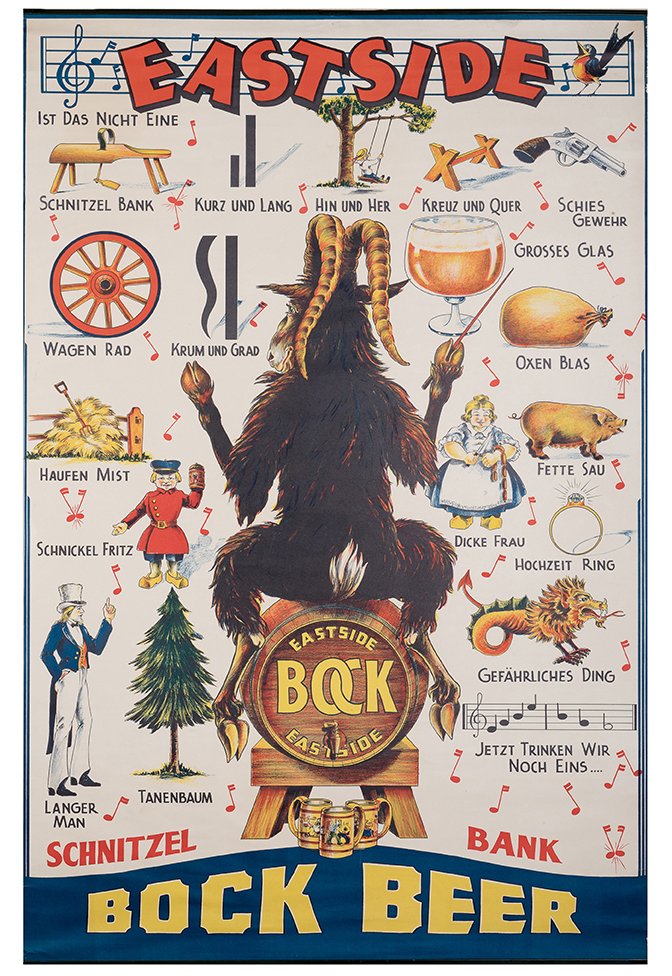

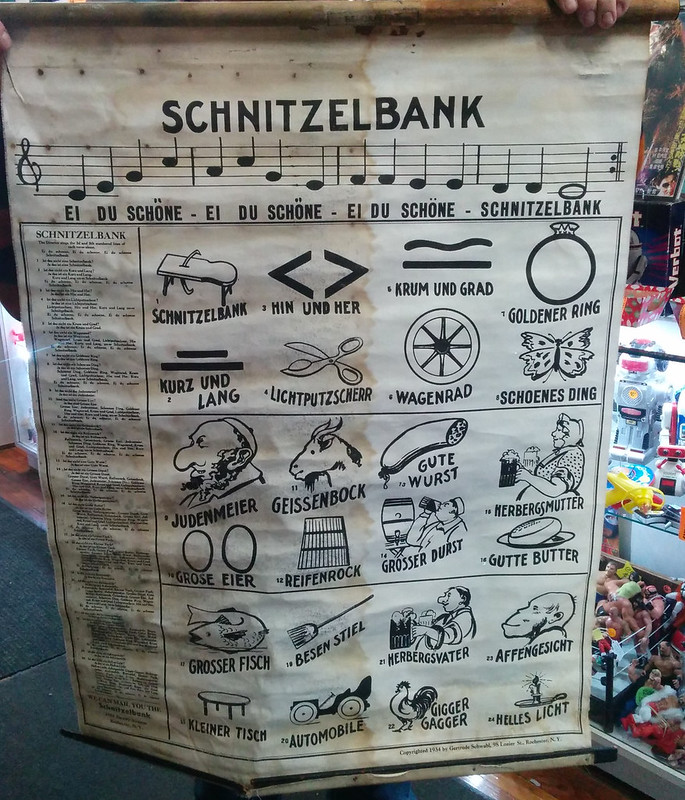

This is the most common version of the poster, and as far as I can tell the symbols have become more or less fixed sometime in the mid-20th century. Perhaps it’s because one company is licensing the imagery to various purposes, or the song has simply evolved to its modern form, made easier by recordings and a growing number of shared experiences.

So let’s break down the most common version of the song:

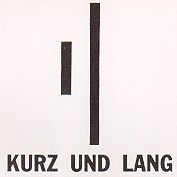

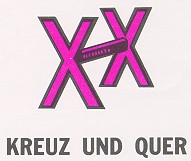

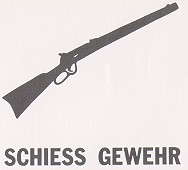

| Symbol | Translation |

|---|---|

|

Is this not a Schnitzelbank?

(“Yes this is a Schnitzelbank”) |

|

Short and Long |

|

Him and Her |

|

Criss and Cross |

|

Shooting Gun |

|

Wagon Wheel |

|

Crooked and Straight |

|

Big Glass |

|

Oxen Bladder |

|

Heap of Manure |

|

Cantankerous Boy |

|

Heavy Woman |

|

Fat Sow |

|

Tall Man |

|

Fir Tree |

|

Wedding Ring |

|

Dangerous Thing |

From Mader’s Famous Restaurant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

From Mader’s Famous Restaurant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.Here’s another band performing the song. This is the Gootman Sauerkraut Band at the Bravarian Pretzel Factory 2014.

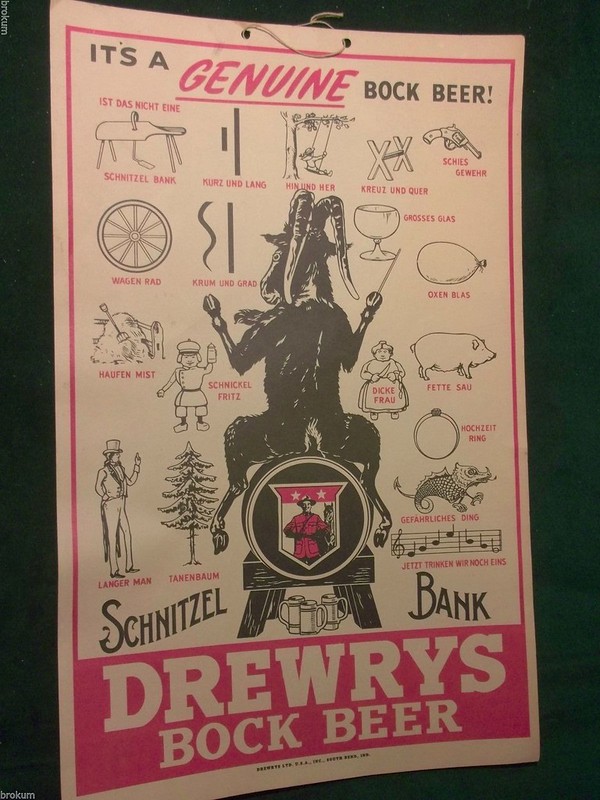

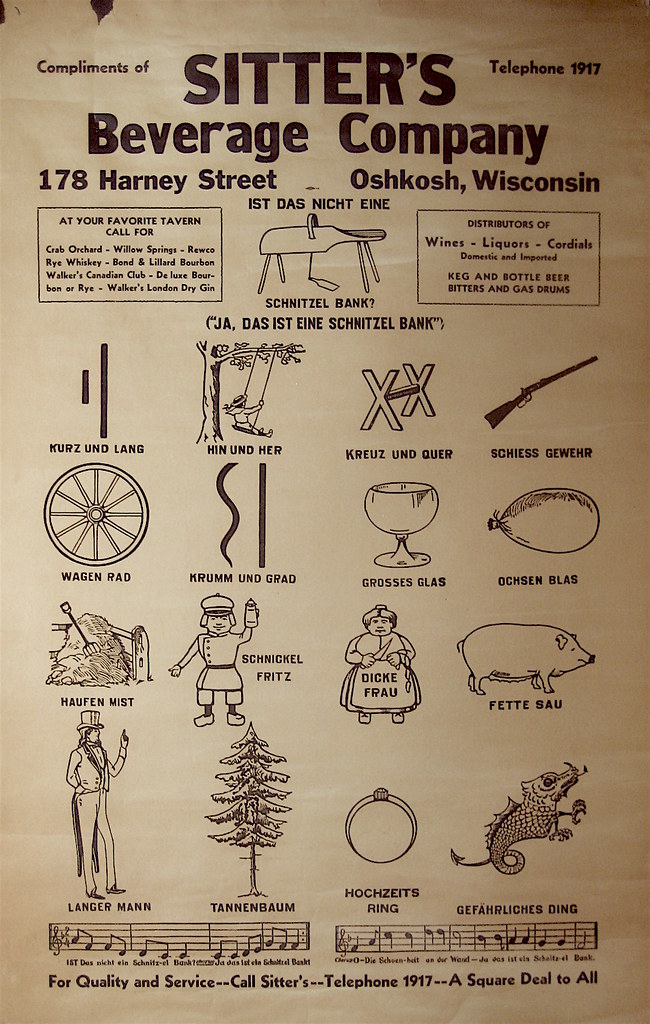

As I mentioned, this all started because a brewery used the Schnitzelbank poster as an advertisement. Apparently that was not unique, and I’ve find a number of others who did likewise. Here’s a few of them:

The Eastside Brewery of Los Angeles, California, from the 1930s.

Drewery’s, the Canadian brewery, from the 1940s.

The Huebner Brewery of Toldeo, Ohio, from sometime prior to prohibition.

This one, though not for a specific brewery, was for Sitter’s Beverages, a distributor of beer, wine, liquor and cordials in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. It’s undated, but given that the telephone number is “1917” (yes, just those four numbers) I suspect it’s pre-prohibition. One source puts the date between 1912 and 1919.

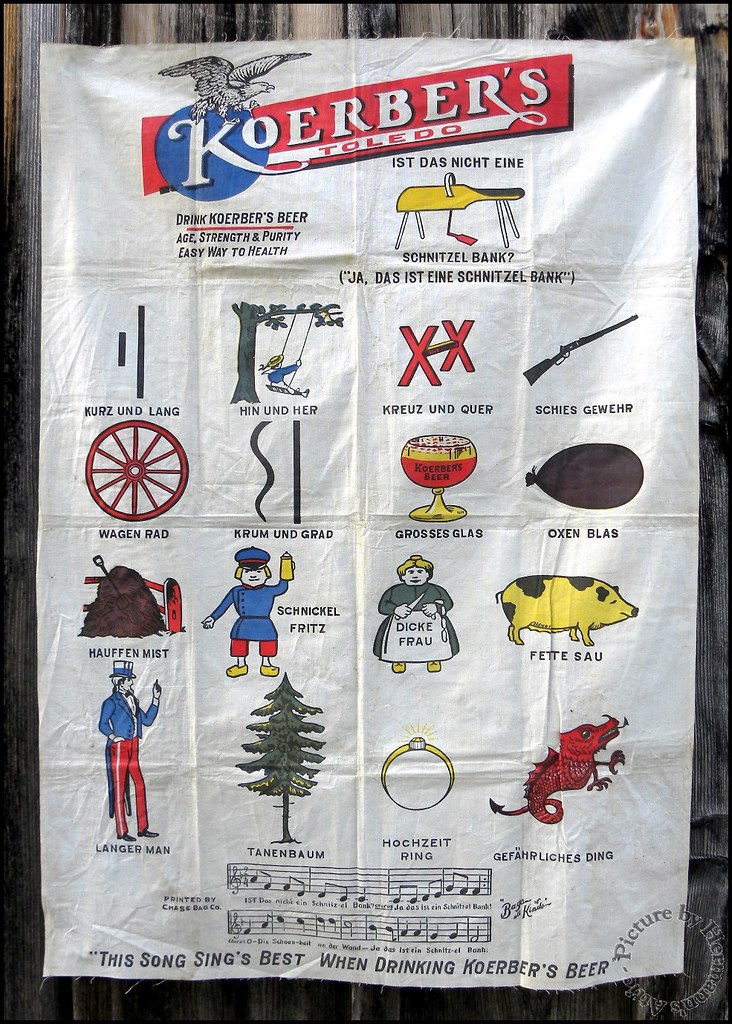

A promotional towel, from Koerber’s Brewery, also from Toledo, Ohio.

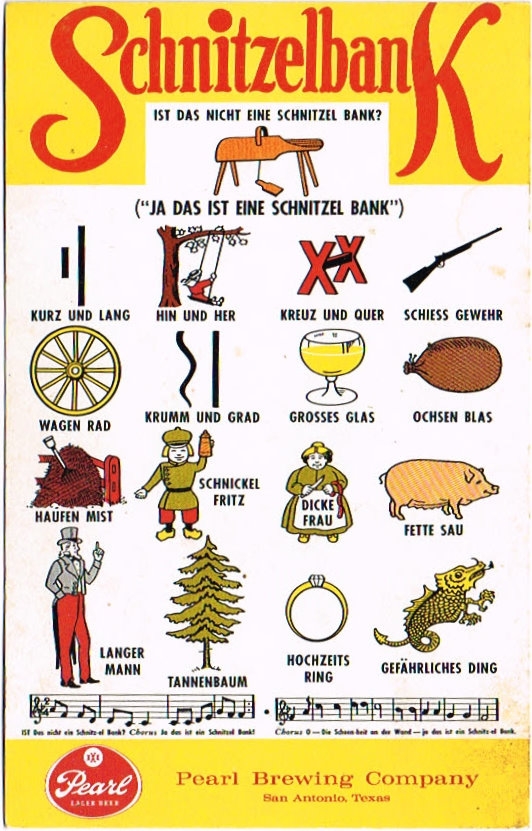

The Pearl Brewery of San Antonio, Texas

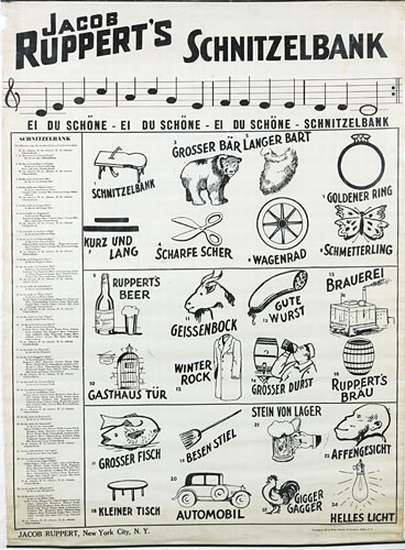

Jacob Ruppert’s Brewery of New York City, 1907. Though notice that the almost uniform symbols were changed for Ruppert’s ad, substituting his own beer and brewery, along with other more beer-friendly items into the song list.

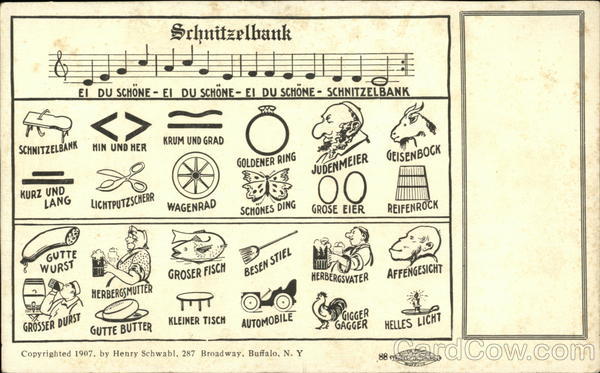

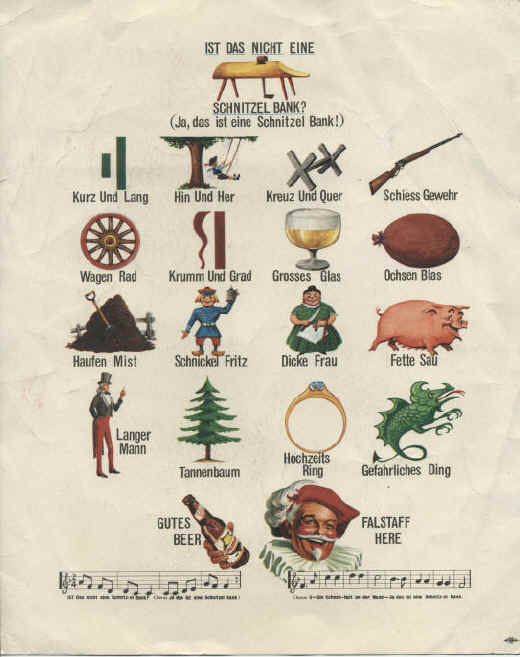

Although it’s possible that the symbols weren’t quite as settled in the early 20th century, as this postcard, also from 1907, has several that deviate from the standard symbols, including some also in the Ruppert’s poster, but also some that are not in that one.

Yuengling Brewery also apparently had their own Schnitzelbank poster, based on the Ruppert’s design. This one is a linen towel being used as a window shade, though it’s too small for me to read the date.

Though the Ruppert’s design appears to be copyrighted again in 1934, based on this generic one found by someone in an antique store.

Likewise, this one for Falstaff Beer uses the traditional symbols, but adds two more, one for “Gutes Bier” (good beer) and “Falstaff Here.”

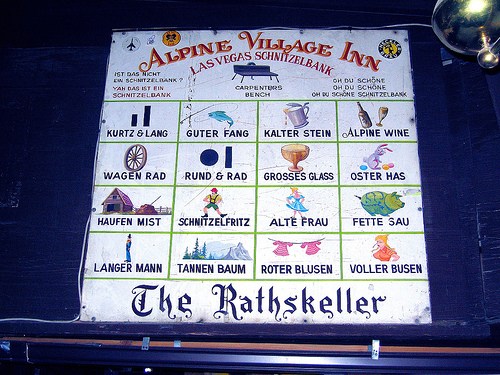

This one’s also not from a brewery, but the Alpine Village Inn in Las Vegas, Nevada. This one’s newer, as it opened in 1950, became somewhat famous, but then closed in 1970.

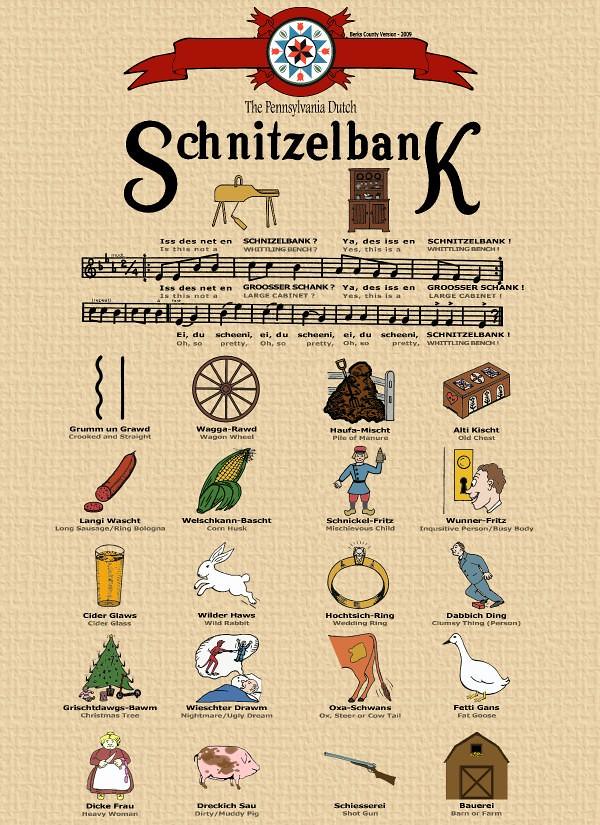

This one is labeled as being a “Pennsylvania Dutch Schnitzelbank” and has 20 symbols rather than the standard sixteen. And only eight of those are the usual ones. I don’t know how I missed it growing up (I grew up near Pennsylvania Dutch country in Pennsylvania, and in fact my grandparents grew up on Mennonite farms, but were the first generation to leave them).

Apparently it’s also a big deal in Amana, Iowa, where there’s a gift and toy store called the “Schnitzelbank” and where, in 1973, the Amana Society created this Schnitzelbank poster.

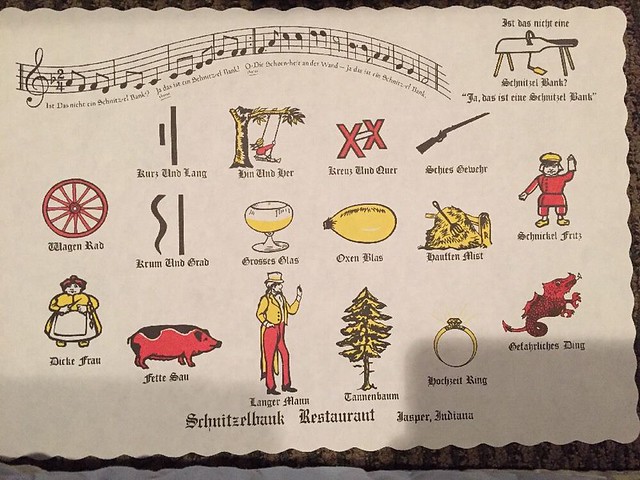

The Schnitzelbank Restaurant in Jasper, Indiana, uses the poster as their placemats.

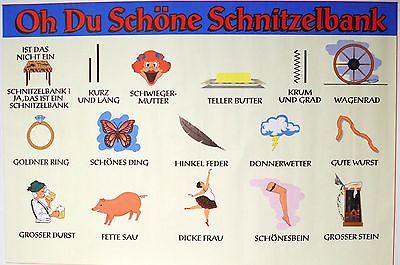

This random German poster, which translates as “Oh you beautiful Schnitzelbank” has only about half of the standard symbols on it. I’m not sure when this one was created but it’s available on Polka Time as an “Oktoberfest Poster.”

Also more modern, the New Paltz Band has their own version of the song using non-standard symbols.

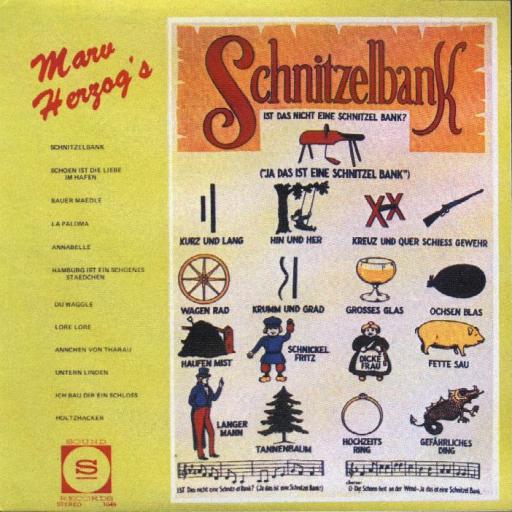

And speaking of music, Marv Herzog used the poster on an album cover. The album, of course, included the Schnitzelbank song.

And lastly, the Animanics did their own version of the Schnitzelbank song in episode 56 entitled “Schnitzelbank,” which aired in 1994. It’s described as “a traditional German song that the Warners learn in German from Prof. Otto von Schnitzelpusskrankengescheitmeyer. The lyrics were adapted by Randy Rogel.”

From Henry Sticht’s “Schnitzelbank Two-Step,” 1907.

Is this the most that’s ever been written about the Schnitzelbank song?

In case you are interested, I collect Schnitzelbank-related items, and have over a hundred charts from various breweries, etc. However, I had never seen the Sitter’s Beverage chart before. Thanks for posting it.

I am originally from Jasper, Indiana, home of the Schnitzelbank Restaurant.

@Ron Flick: Would be interested in seeing what you have. Any chance you have pictures somewhere or could upload a video to youtube?

Ever seen this one? I believe many Wuetefeld’s are from Indiana..

https://imgur.com/a/dTZAv

Here are the Kashubian versions of Schnitzelbank from Poland:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4CVNx_9IRZ4

http://belok.kaszubia.com/wiadla/rekordowo-wioldze-note

My father used to have a Schnitzelbank posted in his basement bar room from Koehler Beer, in Erie, PA. I don’t know what happened to it, I think that my sister sold it at a auction. I learned it as a child from my Grandfather. Lots of memories.

Couldn’t help but notice the antisemitism in those older versions: “Judenmeier” depiction of a large-nosed Jew