![]()

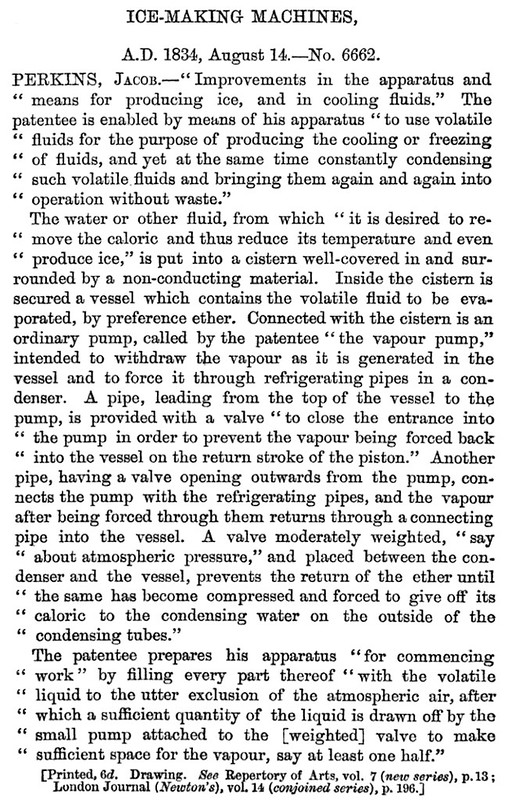

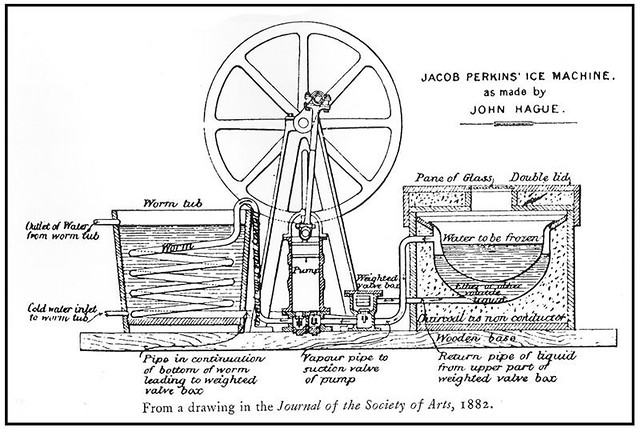

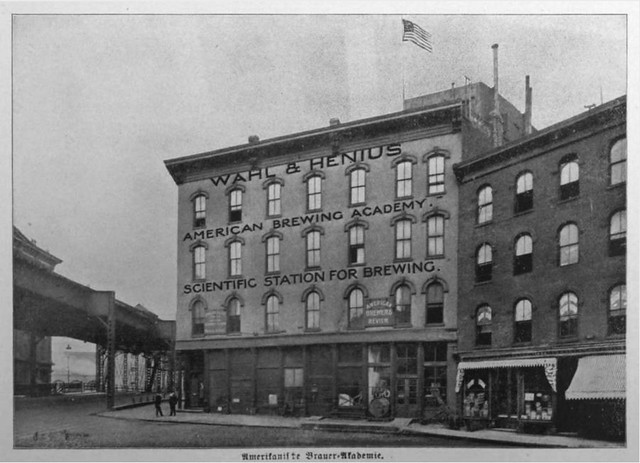

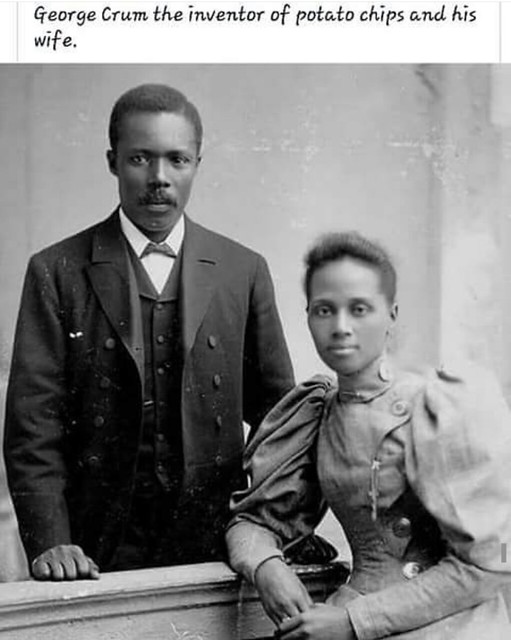

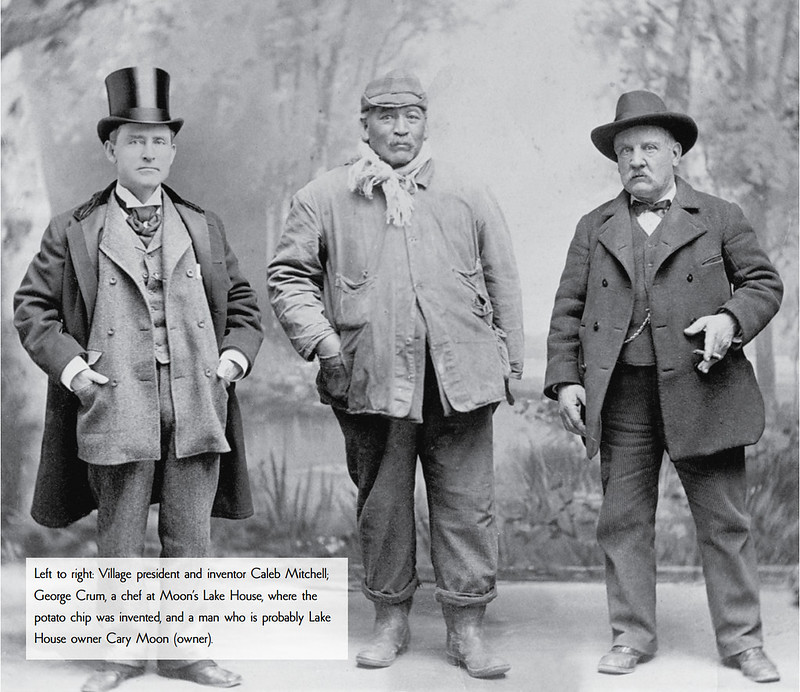

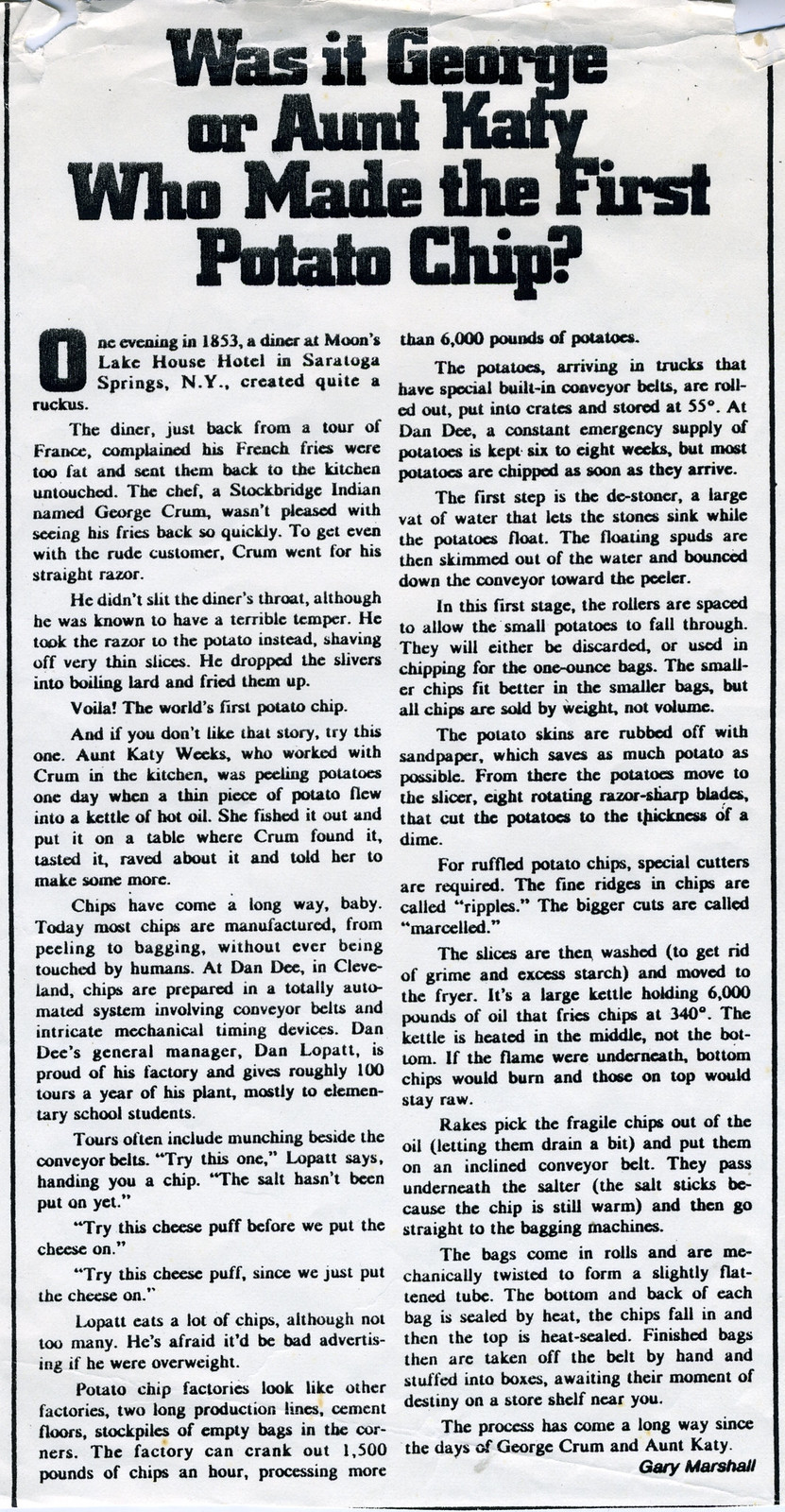

Today is the date that George Crum died in 1914, and the closest anyone knows about when he was born is July 1832, although some accounts say as early as 1822 and at least one more gives 1831. But he was born George Speck, but changed his name to “Crum” (July 1832-July 22, 1914). He worked several jobs before finding his true calling as a chef in upstate New York, most notably at Moon’s Lake House, which was located near Saratoga Springs, New York, and later at his own “Crum’s Place.” But his true fame came from the invention of the potato chip in 1853. There is some controversy about whether he is the true inventor, although there are other candidates, and some evidence that either way he may have been involved at some level, he remains the likeliest person to be credited with inventing the potato chip, which makes him a hero in my book.

When George W. Speck-Crum was born in July 1828 in Malta, New York, his father, Abraham, was 39 and his mother, Catherine, was 42. He had three sons and one daughter with Elizabeth J. He then married Hester Esther Bennett in 1860. He died on July 22, 1914, in his hometown, having lived a long life of 86 years, and was buried in Saratoga County, New York.

Nothing about his life seems particularly settled, not his birthday, where he was born, his exact ethnicity, or almost anything else, but here’s what Wikipedia claims:

George Speck (also called George Crum) was a man of mixed ancestry, including St. Regis (Akwesasne) Mohawk Indian, African-American, and possibly German. He worked as a hunter, guide, and cook in the Adirondacks, who became renowned for his culinary skills after being hired at Moon’s Lake House on Saratoga Lake, near Saratoga Springs, New York.

Speck’s specialities included wild game, especially venison and duck, and he often experimented in the kitchen. During the 1850s, while working at Moon’s Lake House in the midst of a dinner rush, Speck tried slicing the potatoes extra thin and dropping it into the deep hot fat of the frying pan. Thus was born the potato chip.

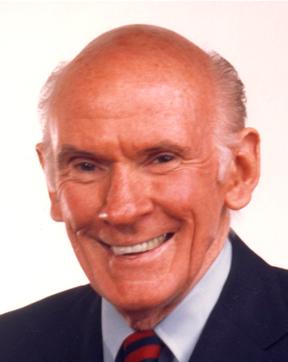

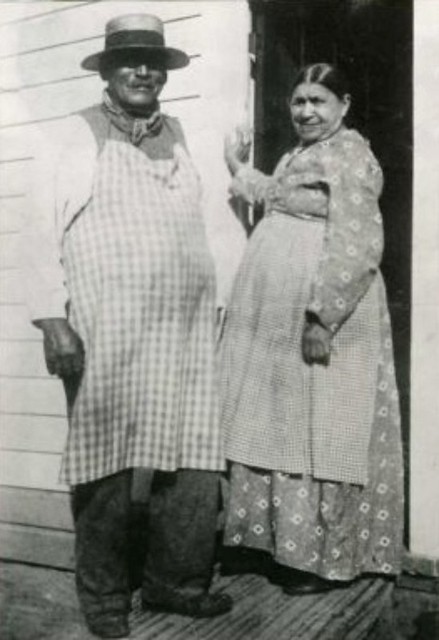

George and his wife Kate.

George and his wife Kate.George Speck (also called George Crum) was born on July 15, 1824 (or 1825) [maybe, but possibly other years or dates] in Saratoga County in upstate New York. Some sources suggest that the family lived in Ballston Spa or Malta; others suggest they came from the Adirondacks. Depending upon the source, his father, Abraham, and mother Diana, were variously identified as African American, Oneida, Stockbridge, and/or Mohawk Indians. Some sources associate the family with the St. Regis (Akwesasne) Mohawk reservation that straddles the US/Canadian border. Speck and his sister Kate Wicks, like other Native American or mixed-race people of that era, were variously described as “Indian,” “Mulatto,” “Black,” or just “Colored,” depending on the snap judgement of the census taker.

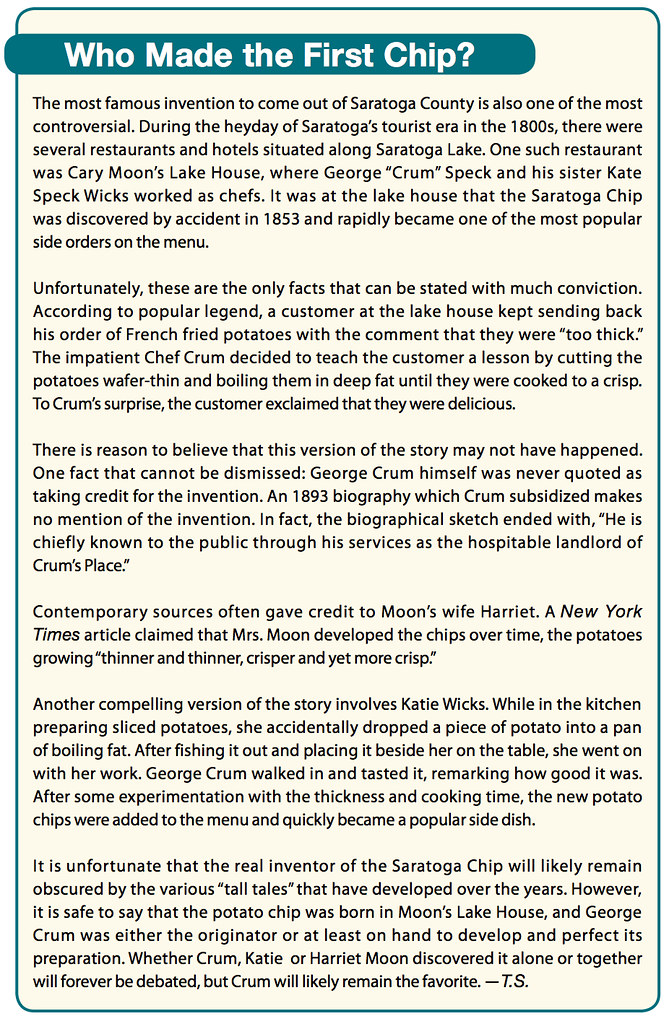

Speck developed his culinary skills at Cary Moon’s Lake House on Saratoga Lake, noted as an expensive restaurant at a time when wealthy families from Manhattan and other areas were building summer “camps” in the area. Speck and his sister, Wicks, also cooked at the Sans Souci in Ballston Spa, alongside another St. Regis Mohawk Indian known for his skills as a guide and cook, Pete Francis. One of the regular customers at Moon’s was Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, who, although he savored the food, could never seem to remember Speck’s name. On one occasion, he called a waiter over to ask “Crum,” “How long before we shall eat?” Rather than take offense, Speck decided to embrace the nickname, figuring that, “A crumb is bigger than a speck.”

Wicks later recalled the invention of the potato chip as an accident: she had “chipped off a piece of the potato which, by the merest accident, fell into the pan of fat. She fished it out with a fork and set it down upon a plate beside her on the table.” Her brother tasted it, declared it good, and said, “We’ll have plenty of these.” In a 1932 interview with the Saratogian newspaper, her grandson, John Gilbert Freeman, asserted Wick’s role as the true inventor of the potato chip.

Speck, however, was the one who popularized the potato chip, first as a cook at Moon’s and then in his own place. By 1860, Speck had opened his own restaurant, called Crum’s, on Storey Hill in nearby Malta, New York. His cuisine was in high demand among Saratoga Springs’ tourists and elites: “His prices were…those of the fashionable New York restaurants, but his food and service were worth it…Everything possible was raised on his own small farm, and that, too, got his personal attention whenever he could arrange it.” According to popular accounts, he was said to include a basket of chips on every table. One contemporaneous source recalls that in his restaurant, Speck was unquestionably the man in charge: “His rules of procedure were his own. They were very strict, and being an Indian, he never departed from them. In the slang of the racecourse, he “played no favorites.” Guests were obliged to wait their turn, the millionaire as well as the wage-earner. Mr. Vanderbilt once was obliged to wait an hour and a half for a meal…With none but rich pleasure-seekers as his guests, Crum kept his tables laden with the best of everything, and for it all charged Delmonico prices.”

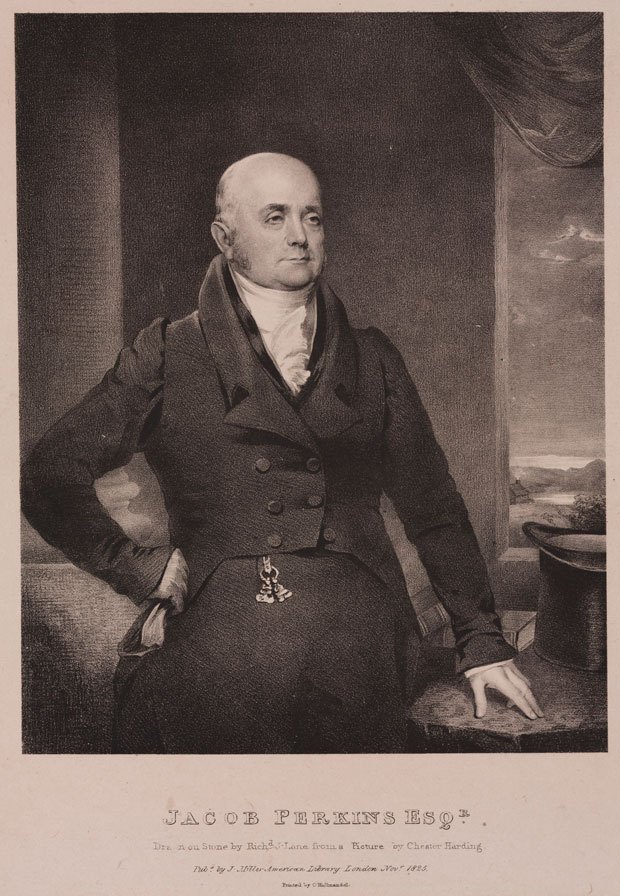

Recipes for frying potato slices were published in several cookbooks in the 19th century. In 1832, a recipe for fried potato “shavings” was included in a United States cookbook derived from an earlier English collection. William Kitchiner’s The Cook’s Oracle (1822), also included techniques for such a dish. Similarly, N.K.M. Lee’s cookbook, The Cook’s Own Book (1832), has a recipe that is very similar to Kitchiner’s.

The New York Tribune ran a feature article on “Crum’s: The Famous Eating House on Saratoga Lake” in December 1891, but, curiously, mentioned nothing about potato chips.[13] Neither did Crum’s commissioned biography, published in 1893, nor did one 1914 obituary in a local paper.[14] Another obituary states “Crum is said to have been the actual inventor of “Saratoga chips.””[15] When Wicks died in 1924, however, her obituary authoritatively identified her as follows: “A sister of George Crum, Mrs. Catherine Wicks, died at the age of 102, and was the cook at Moon’s Lake House. She first invented and fried the famous Saratoga Chips.”

Hugh Bradley’s 1940 history of Saratoga contains some information about Speck, based on local folklore as much as on any specific historical primary sources. Fox and Banner said that Bradley had cited an 1885 article in the Hotel Gazette about Speck and the potato chips. Bradley repeated several myths that appear in that article, including that “Crum was born in 1828, the son of Abe Speck, a mulatto jockey who had come from Kentucky to Saratoga Springs and married a Stockbridge Indian woman,” and that, “Crum also claimed to have considerable German and Spanish blood.”

Cary Moon, owner of Moon’s Lake House, rushed to claim credit for the invention, and began mass-producing the chips, first served in paper cones, then packaged in boxes. They soon became wildly popular: “It was at Moon’s that Clio first tasted the famous Saratoga chips, said to have originated there, and it was she who first scandalized spa society be strolling along Broadway and about the paddock at the race track crunching the crisp circlets out of a paper sack as though they were candy or peanuts. She made it the fashion, and soon you saw all Saratoga dipping into cornucopias filled with golden-brown paper-thin potatoes; a gathered crowd was likely to create a sound like a scuffling through dried autumn leaves.” Visitors to Saratoga Springs were advised to take the 10-mile journey around the lake to Moon’s if only for the chips: “the hobby of the Lake House is Fried Potatoes, and these they serve in good style. They are sold in papers like confectionary.”

A 1973 advertising campaign by the St. Regis Paper Company, which manufactured packaging for chips, featured an ad for Crum (Speck) and his story, published in the national magazines, Fortune and Time. During the late 1970s, the variant of the story featuring Vanderbilt became popular because of the interest in his wealth and name, and evidence suggests the source was an advertising agency for the Potato Chip/Snack Food Association.

A 1983 article in Western Folklore identifies potato chips as having originated in Saratoga Springs, New York, while critiquing the variants of popular stories. In all versions, the chips became popular and subsequently known as “Saratoga chips” or “potato crunches”.

The 21st-century Snopes website writes that Crum’s customer, if he existed, was more likely an obscure one. Vanderbilt was a regular customer at Moon’s Lake House and at Crum’s Malta restaurant, but there is no evidence that he played any role in inventing (or demanding) potato chips.

And here’s yet another story about the origin of the potato chip, written by Jean McGregor in the Saratogian in 1940:

The authentic story of Saratoga chips is at long last revealed by the great nephew of George (Speck) Crum, their originator, Albert J. Stewart, now an employee of Mrs. Webster Curran Moriarta of North Broadway, with whom he has been employed for 24 years. Stewart told the story to Mrs. Moriarta many times as I relate it here: “Aunt Kate Wicks” so called by her friends, had something* to do with their Invention—worked for her brother, Crum. She related the true circumstances to Stewart many times before her death in 1914 at 68 William St., where she resided. Crum was born in Malta, the son of Abram Speck, a mulatto jockey who came from Kentucky in the early days of Saratoga and married an Indian woman of the Stockbridge tribe. It is related that a wealthy dinner guest had one time Jokingly referred to the name Speck, as Crura, and thereupon Speck took over the name of Crum. George Crum was more Indianin appearance. His younger days were spent in the Adirondack^ and he became a mighty hunter and a successful fisherman. His services as a guide in the Adirondack* were much sought after. His companion in the forests was a Frenchman from whom he learned to cook. Shortly after the Frenchman’s death, Cnrn took up his abode near the south end of the lake and prepared to serve ducks. He became known throughout the country for his unique and wonderful skill In cooking game, fish and camp fire dishes generally. While he was employed as a cook at Moon’s Place, opened by Carey B. Moon in 1853 at the Southend of Saratoga Lake, on the Ramsdill Road, the incident occurred which led to the making of Saratoga Chips. “Aunt Kate Wicks” who worked with her brother, Crum, making pastry, had a pan of fat on the stove, while making crullers and was peeling potatoes at the same time. She chipped off a piece of potato which by the merest accident fell into the pan of fat. She fished it out with a fork and set it down upon a plate beside her on the table. Crum came into the kitchen. “What’s this?”, he asked, as he picked up the chip and tasted it “Hm, Hm, that’s good. How did you make it?” “Aunt Kate” described the accident. “That’s a good accident,” said Crum. “We’ll have plenty of these.” HE TREED them out. Demand for them grew like wild fire and he sold them at 15 and ten cents a bag. Thus the Saratoga Chip came into existence. Other makes appeared on the market as time passed. For a long period of years, few prominent men in the world of finance, politics, art, the drama or sports, failed to eat one of Crum’s famous dinners.

The late Cornelius E. Durkee, who died at the age of 96, entertained many guests at Moon’s and was familiar with its history, related this interesting story of Crum’s genius as a cook for me one day while he was compiling his reminiscences: “William H. Vanderbilt, father of Governor William H. Vanderbilt of Rhode Island, a prominent visitor here in those days, was extremely fond of canvasback ducks, but could not get them cooked properly in the village. “He sent a couple to Crum to see what he could do with them. “Crum had never seen a canvasback but having boasted that he could cook anything, willingly undertook to prepare these. “I KEPT THEM over the coals 19 minutes.” Crum told Mr. Durkee, “the blood following the knife and sent them to the table hot. Mr. Vanderbilt said he had never eaten anything like them in his life”Mr. Vanderbilt,” continued Mr. Durkee, “was so pleased he sent Mr. Crum many customers. He prospered in the business. He kept his tables laden with the best of everything and did not neglect to charge Delmonico prices.” “His rules of procedure were his own. Guests were obliged to wait their turn, the millionaire as well as the wage earner. Mr. Vanderbilt was once obliged to wait an hour for a meal and Jay Gould and his party, also visitors here in the early days when this resort was the capital of fashionables of the country, waited as long another time. CRUM LEFT the kitchen to apologize to Mr. Gould, who told him he understood the rules of the establishment and would wait willingly another hour. Judge Hilton and a party of friends were turned away one day. “I can’t wait on you,” said Crum, directing them to a rival house for dinner. “George,” said Mr. Hilton, “you must wait on us if we have to remain in the front yard for two hours.” Mr. Durkee recalled for me that, among those who enjoyed Crum’s cooking and his potato chips were Presidents Chester A. Arthur and Grover Cleveland, and Governors Horatio Seymour, Alonzo B. Cornell, David P. Hill, Roswell P. Flower and such financiers as Vanderbilt, Pierre Lorillard, Berry Wall, William R. Travers, William M. Tweed and E. T. Stokes. Crum died in 1914. His brother, Abraham (Speck) Crum dug out an old Indian canoe for Jonathan Ramsdill of Saratoga Lake which is still on exhibit in the State Museum in Albany as one of the finest examples of Indian canoes and Indian days at Saratoga Lake, rich in Indian lore.

And Original Saratoga Chips in New York, also has their version of the story on their website. And The Great Idea Finder also has some info on Crum.

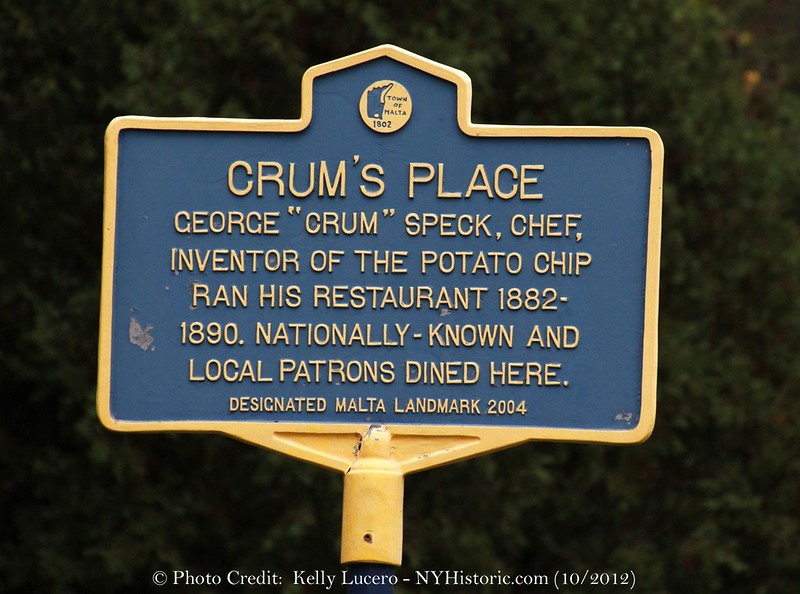

His own restaurant, Crum’s Place, was located at 793 Malta Avenue in Ballston Spa, New York. Today, a marker can be seen by the spot where it stood from 1860-1890.

William in the back, having our first beer in Brussels a few years ago.

William in the back, having our first beer in Brussels a few years ago. William with Tom Peters.

William with Tom Peters. Sporting a Unicorn.

Sporting a Unicorn. William, with Scoats and Tom Peters as I shared Belgian frites with everyone in Brussels a few years ago.

William, with Scoats and Tom Peters as I shared Belgian frites with everyone in Brussels a few years ago.