Today is the feast day of St. Brigid (c. 451 CE–525 CE). She is a patron saint of brewers. She was also known as Bride, Bride of the Isles, Bridget of Ireland, Bridget, Brigid of Kildare, Brigit, Ffraid, and Mary of the Gael. She is one of Ireland’s patron saints, along with Patrick and Columba. Irish hagiography makes her an early Irish Christian nun, abbess, and foundress of several monasteries of nuns, including that of Kildare in Ireland, which was famous and was revered. Her feast day is February 1, which was originally a pagan festival called Imbolc, marking the beginning of spring. Her feast day is shared by Dar Lugdach, who tradition says was her student, close companion, and the woman who succeeded her. She also a patron saint of brewers. “Brigid, who had a reputation as an expert dairywoman and brewer, was reputed to turn water into beer.”

Here’s account of her life, from Wikipedia:

Probably the earliest biography, Vita Sanctae Brigitae (Life of St. Brigid), was written by Cogitosus, a 7th century monk of Kildare. A second, Vita Prima Sanctae Brigitae (First Life of St. Brigid), by an unknown author, is sometimes attributed to St. Broccán Clóen (d. 650). The book of uncertain authorship is occasionally argued to be the first written biography of St. Brigid, though most scholars reject this claim.

A Vita sometimes attributed to St. Coelan of Inishcaltra in the early 7th century derives further speculation from the fact that a foreword was added, ostensibly in a subsequent edition, by St. Donatus, also an Irish monk, who became Bishop of Fiesole in 824. In his foreword, Donatus refers to earlier biographies by St. Ultan and St. Ailerán. The manuscript of Vita III, as it has come to be known, was preserved in the Italian monastery of Monte Cassino until its destruction during World War II. As the language used is not that of St. Coelan’s time, philologists remain uncertain of both its authorship and century of origin. Discussion on dates for the annals and the accuracy of dates relating to St. Brigid continues.

Early life

According to tradition, Brigid was born in the year 451 AD in Faughart, just north of Dundalk in County Louth, Ireland. Because of the legendary quality of the earliest accounts of her life, there is debate among many secular scholars and Christians as to the authenticity of her biographies. Three biographies agree that her mother was Brocca, a Christian Pict slave who had been baptized by Saint Patrick. They name her father as Dubhthach, a chieftain of Leinster.

The vitae says that Dubthach’s wife forced him to sell Brigid’s mother to a druid when she became pregnant. Brigid herself was born into slavery. Legends of her early holiness include her vomiting when the druid tried to feed her, due to his impurity; a white cow with red ears appeared to sustain her instead.

As she grew older, Brigid was said to have performed miracles, including healing and feeding the poor. According to one tale, as a child, she once gave away her mother’s entire store of butter. The butter was then replenished in answer to Brigid’s prayers. Around the age of ten, she was returned as a household servant to her father, where her habit of charity led her to donate his belongings to anyone who asked.

In both of the earliest biographies, Dubthach is portrayed as having been so annoyed with Brigid that he took her in a chariot to the King of Leinster to sell her. While Dubthach was talking to the king, Brigid gave away his bejeweled sword to a beggar to barter it for food to feed his family. The king recognized her holiness and convinced Dubthach to grant his daughter freedom.

Religious life

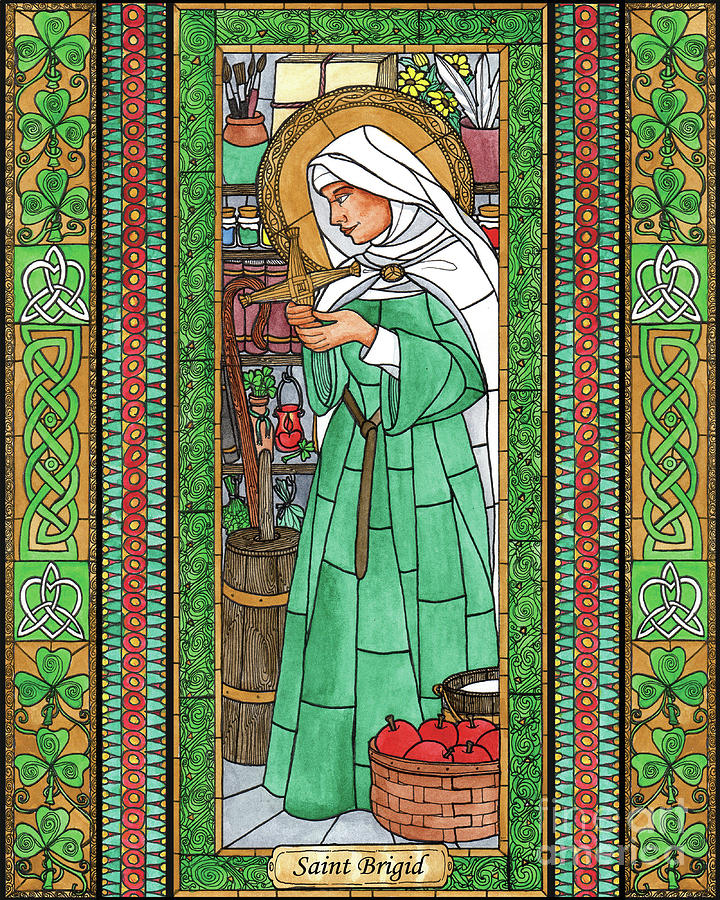

Saint Brigid as depicted in Saint Non’s chapel, St Davids, Wales.

It is said that Brigid was “veiled” or received either by St. Mac Caill, Bishop of Cruachu Brig Ele (Croghan, County Offaly), or by St. Mél of Ardagh at Mág Tulach (the present barony of Fartullagh, County Westmeath), who granted her abbatial powers. It is said that in about 468, she and a Bishop MacCaille followed St. Mél into the Kingdom of Tethbae, which was made up of parts of the modern counties Meath, Westmeath and Longford.According to tradition, around 480 Brigid founded a monastery at Kildare (Cill Dara: “church of the oak”), on the site of a pagan shrine to the Celtic goddess Brigid, served by a group of young women who tended an eternal flame. The site was under a large oak tree on the ridge of Drum Criadh.

Brigid, with an initial group of seven companions, is credited with organizing communal consecrated religious life for women in Ireland. She founded two monastic institutions, one for men, and the other for women, and invited Conleth (Conláed), a hermit from Old Connell near Newbridge, to help her in Kildare as pastor of them. It has often been said that she gave canonical jurisdiction to Conleth, Bishop of Kildare, but Archbishop Healy says that she simply “selected the person to whom the Church gave this jurisdiction”, and her biographer tells us that she chose Saint Conleth “to govern the church along with herself”. For centuries, Kildare was ruled by a double line of abbot-bishops and of abbesses, the Abbess of Kildare being regarded as superior general of the monasteries in Ireland. Her successors have always been accorded episcopal honour. Brigid’s oratory at Kildare became a centre of religion and learning, and developed into a cathedral city.

Brigid is credited with founding a school of art, including metalwork and illumination, which Conleth oversaw. The Kildare scriptorium made the Book of Kildare, which drew high praise from Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis), but disappeared during the Reformation. According to Giraldus, nothing that he ever saw was at all comparable to the book, every page of which was gorgeously illuminated, and the interlaced work and the harmony of the colours left the impression that “all this is the work of angelic, and not human skill”.

According to the Trias Thaumaturga Brigid spent time in Connacht and founded many churches in the Diocese of Elphin. She is said to have visited Longford, Tipperary, Limerick, and South Leinster. Her friendship with Saint Patrick is noted in the following paragraph from the Book of Armagh: “inter sanctum Patricium Brigitanque Hibernesium columpnas amicitia caritatis inerat tanta, ut unum cor consiliumque haberent unum. Christus per illum illamque virtutes multas peregit” (Between St. Patrick and St. Brigid, the pillars of the Irish people, there was so great a friendship of charity that they had but one heart and one mind. Through him and through her Christ performed many great works.)

Her exploits appear to have included beer on more than on occasion, as detailed by journalist Jack Beresford in an article for the Irish Post last year.

One of Ireland’s three patron saints alongside St Colmcille and St Patrick, the feast of St Brigid also happens to fall on the Celtic first day of spring, Imbolc.

There are plenty of stories surrounding St Brigid, but few are as famous, fun or fascinating as the tale about how she supposedly turned some ordinary bathwater into beer.

The story goes that one day, while working in a leper colony, she discovered to her horror that they had run out of beer.

It’s important to understand that in those times, centuries ago, beer was consumed on a daily basis as a source of hydration and nourishment.

As opposed to today, of course, when…oh wait, scratch that.

In any case, back in those times many of the water sources close to villages and towns were often polluted to the point where consumption would likely result in illness or, worse still, death.

Alcohol offered an (almost) germ free alternative and was almost as good as any meal of the era.

So, to be faced with a beer drought was nothing short of disastrous.

Not that it mattered all that much to St Brigid.

Channelling a little divine intervention, she answered the prayers of the thirsty lepers under her charge by turning the water they used to bathe into not just any beer, but a genuinely brilliant beer that was enjoyed by one and all.

Her water-based exploits don’t end there either.

Another part of the legend says St Brigid also succeeded in turning dirty bathwater into beer for the clerics visiting the leper colony where she was based.

There’s even a tale of her supplying some eighteen churches with enough beer to last from Holy Thursday through to the end of Easter despite only having one barrel to her name.

Whether fact or fiction, one thing appears undeniable: St Brigid liked beer.

Though perhaps this 10th century poems captures Brigid’s commitment to beer best. It’s entitled “I’d like to give a lake of beer to God.”

I’d like to give a lake of beer to God.

I’d love the heavenly

Host to be tippling there

For all eternity.I’d love the men of Heaven to live with me,

To dance and sing.

If they wanted, I’d put at their disposal

Vats of suffering.White cups of love I’d give them

With a heart and a half;

Sweet pitchers of mercy I’d offer

To every man.I’d make Heaven a cheerful spot

Because the happy heart is true.

I’d make the men contented for their own sake.

I’d like Jesus to love me too.I’d like the people of heaven to gather

From all the parishes around.

I’d give a special welcome to the women,

The three Marys of great renown.I’d sit with the men, the women and God

There by the lake of beer.

We’d be drinking good health forever

And every drop would be a prayer.

And this is part of an account of Brigid entitled “Wild Irish Women: Saint Brigid – Mary of the Gaels” by Rosemary Rogers for Irish American.

Despite all her accomplishments, her legend grew because of her many miracles, so resonant with Irish mysticism: she taught a fox to dance, tamed a wild boar, hung her damp cloak (that cloak again!) on a sunbeam to dry, obliging the sunbeam to remain all night. In her later years, her powers took on almost Christ-like proportions – she could multiply food, exorcise demons with a casual sign of the cross, and calm storms. Proving she was someone you’d like to have a beer with, Brigid, fond of the brew herself, could produce bottomless barrels and turn both milk and water into ale. Once, while curing lepers, she learned there was nothing to drink and used her own bathwater to stand the entire colony to a pint.