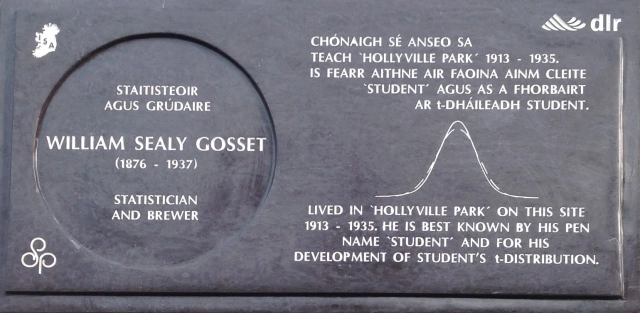

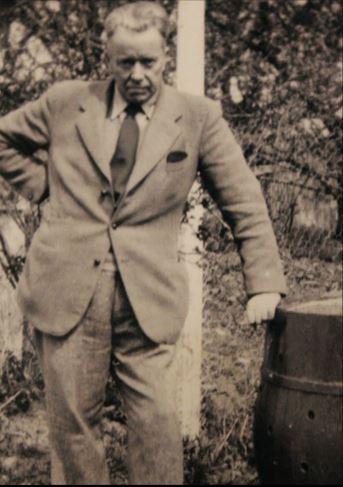

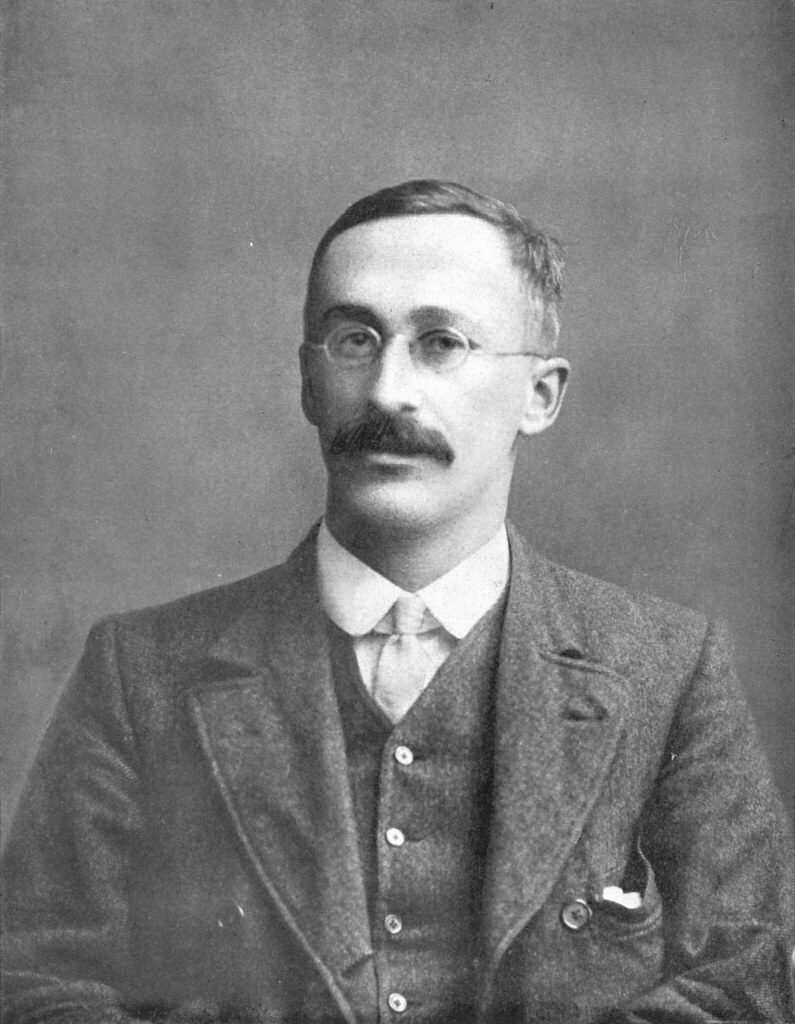

Today is the birthday of William Sealy Gosset (June 13, 1876–October 16, 1937). He “was an English statistician. He published under the pen name Student, and developed the Student’s t-distribution.” He also worked his entire career for Guinness Brewing, and was trained as a chemist, but it was his pioneering work in statistics, in which he was self-taught, that he is best remembered for today.

Here’s his biography, from Wikipedia:

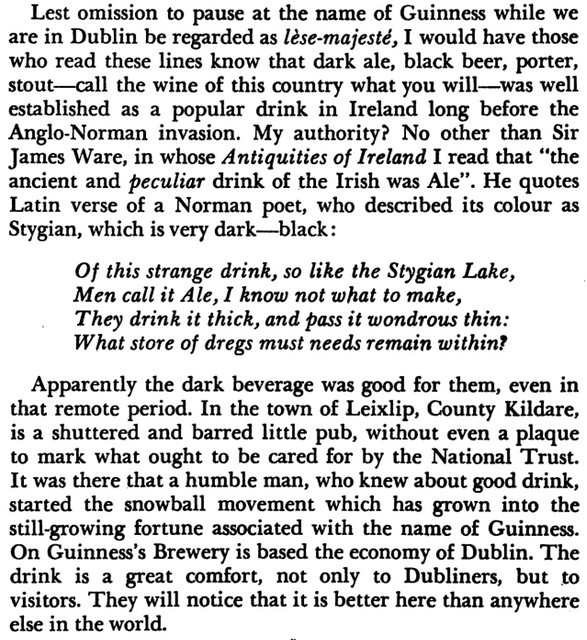

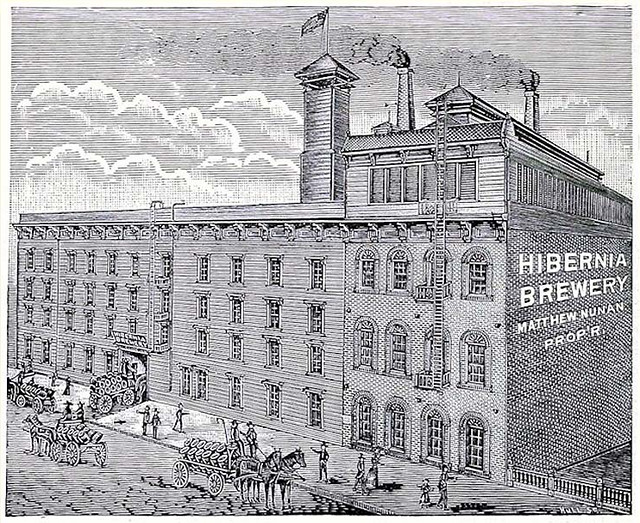

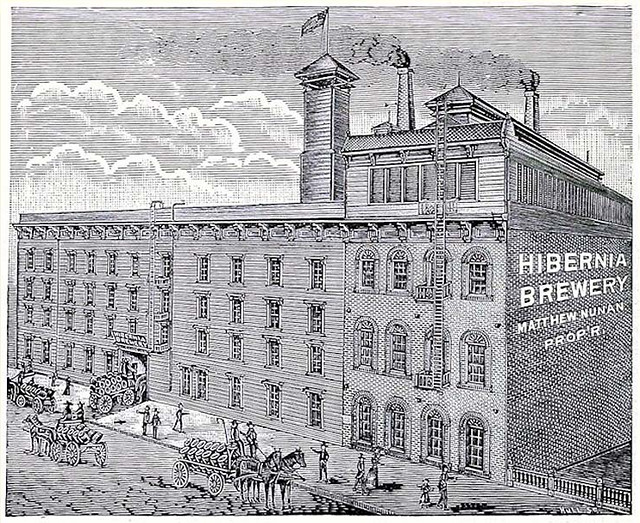

Born in Canterbury, England to Agnes Sealy Vidal and Colonel Frederic Gosset, Gosset attended Winchester College before studying chemistry and mathematics at New College, Oxford. Upon graduating in 1899, he joined the brewery of Arthur Guinness & Son in Dublin, Ireland.

As an employee of Guinness, a progressive agro-chemical business, Gosset applied his statistical knowledge – both in the brewery and on the farm – to the selection of the best yielding varieties of barley. Gosset acquired that knowledge by study, by trial and error, and by spending two terms in 1906–1907 in the biometrical laboratory of Karl Pearson. Gosset and Pearson had a good relationship. Pearson helped Gosset with the mathematics of his papers, including the 1908 papers, but had little appreciation of their importance. The papers addressed the brewer’s concern with small samples; biometricians like Pearson, on the other hand, typically had hundreds of observations and saw no urgency in developing small-sample methods.

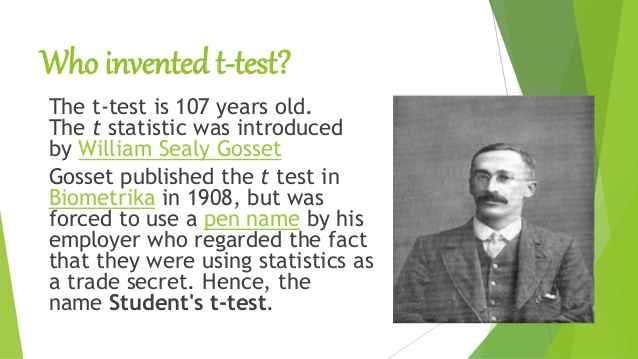

Another researcher at Guinness had previously published a paper containing trade secrets of the Guinness brewery. To prevent further disclosure of confidential information, Guinness prohibited its employees from publishing any papers regardless of the contained information. However, after pleading with the brewery and explaining that his mathematical and philosophical conclusions were of no possible practical use to competing brewers, he was allowed to publish them, but under a pseudonym (“Student”), to avoid difficulties with the rest of the staff. Thus his most noteworthy achievement is now called Student’s, rather than Gosset’s, t-distribution.

Gosset had almost all his papers including The probable error of a mean published in Pearson’s journal Biometrika under the pseudonym Student. It was, however, not Pearson but Ronald A. Fisher who appreciated the importance of Gosset’s small-sample work, after Gosset had written to him to say I am sending you a copy of Student’s Tables as you are the only man that’s ever likely to use them!. Fisher believed that Gosset had effected a “logical revolution”. Fisher introduced a new form of Student’s statistic, denoted t, in terms of which Gosset’s statistic was {\displaystyle z={\frac {t}{\sqrt {n-1}}}} z=\frac{t}{\sqrt{n-1}}. The t-form was adopted because it fit in with Fisher’s theory of degrees of freedom. Fisher was also responsible for applications of the t-distribution to regression analysis.

Although introduced by others, Studentized residuals are named in Student’s honour because, like the problem that led to Student’s t-distribution, the idea of adjusting for estimated standard deviations is central to that concept.

Gosset’s interest in the cultivation of barley led him to speculate that the design of experiments should aim not only at improving the average yield but also at breeding varieties whose yield was insensitive to variation in soil and climate, i.e. robust. This principle only appeared in the later thought of Ronald Fisher, and then in the work of Genichi Taguchi during the 1950s.

In 1935, Gosset left Dublin to take up the position of Head Brewer, in charge of the scientific side of production, at a new Guinness brewery at Park Royal in northwestern London. He died two years later in Beaconsfield, England, of a heart attack.

Gosset was a friend of both Pearson and Fisher, a noteworthy achievement, for each had a massive ego and a loathing for the other. He was a modest man who once cut short an admirer with the comment that “Fisher would have discovered it all anyway.”

And this biography is from the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive:

William Sealey Gosset was born on June 13, 1876 in Canterbury, England where he was the oldest of five children. He died at the age of 61 in Beaconsfield, England on October 16, 1937. He attended the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich to b ecome an engineer before he was rejected because of poor eyesight. William Gosset was never employed as a statistician. In a world of quarrelsome statistics, but he got along with everyone. He was a very helpful, quiet, patient and loyal person.

He went to school at Winchester and was well educated before entering the New College in Oxford. Here he won a first degree in chemistry in 1899. After getting his degree as a chemist, he got a job at Guinness brewery in Dublin in 1899, where he did important work on statistics, but her was never hired at a statistician. It was his environment at Guinness’ that made him a statistician. The brewery was interested in how they could make the best beer.

In 1900, the Guinness Research Laboratory was opened, which was head by the most distinguished brewing chemist, Horace Brown. Horace Brown along with the other brews were wondering how to get the raw materials for brewing beer at the cheapest but getting the best. There were many factors that they had to take into account such as varieties of barley and hops, what conditions of dying, cultivation and maturing factors.

After a few years of research, given that they were given a free hand to explore the conditions of brewing. This gave Gosset a chance to work as a statistician. He was able to take the data from the different examples of brewing to help find out which way was the best. As the young brewers work together, it seemed natural for them to take the data to Gosset to solve the numerical problems.

Gosset, in 1903, could calculate standard errors. In 1904 he wrote on the brewing of beer. This report lead to Karl Pearson consulting Gosset. Gosset met Pearson in July of 1905 when they had long talk together. Pearson, in an hour and a half, m ade Gosset understand the theory of standard errors. Gosset went back to the brewery and practiced those method for the next year. The meeting was also successful in which Pearson got Gosset to take up the study of the law of error.

Gosset wrote paper in his spare time under the name “Student.” His paper were on the probability of error of the mean and of the correlation coefficient for publication. Gosset even managed to run cooperative experiments with Hunter a nd Bennett at Ballinacurra, Buffin at Cambridge, and Beaven at Warminster in the testing of seeds against other seeds. Gosset also work with R.A. Fisher. The funny part is that Fisher did not get along Pearson, but Gosset studied under Pearson and also got along with Fisher.

To quickly recap William Gosset, he was born in 1876 and died in 1937. He did mathematical research for beer brewing, but had the problem working with only a small sample size. He work on the concept of probable errror of a mean. He also analysi sed an extended and broad range of problems such as the counting with a haemacytometer, probable error of a correlation coefficient, cereals, agronomy and the Lanarkshire milk experiment.

A very personal friend, McMullen, said this about Gosset, “he was a very kindly and tolerant and absolutely devoid malice. He rarely spoke about personal matters but when his opinion was well worth listening to and not in the least superficia l.”

Pricenomics has a good overview of Gossett’s contributions to mathematics and statistics, entitled The Guinness Brewer Who Revolutionized Statistics.