![]()

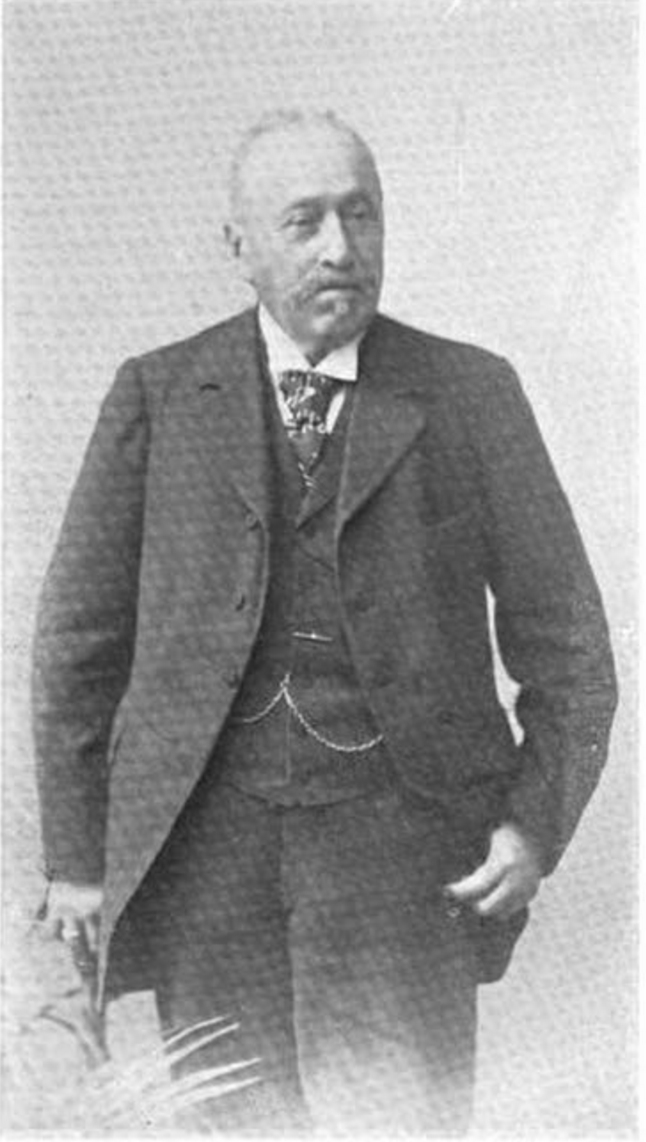

Today is the birthday of Charles Engel (February 11, 1816-June 2, 1900). was born in Stadtgemeinde Bremen, in Bremen, Germany. He emigrated to Philadelphia when he was 29, in 1840, and began brewing there, first as Engel and Wolf’s, and later as Bergner & Engel’s.

Here’s his obituary from the American Brewers Review of July 1900.

Here’s his story, from “100 Years of Brewing,” recounting his role in brewing some of the first lagers in America:

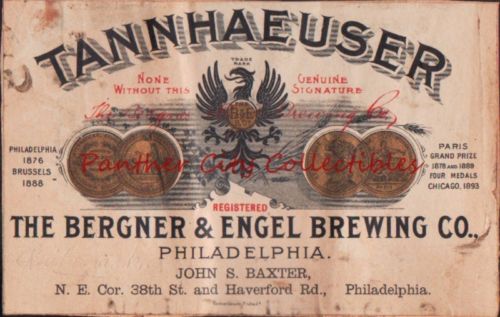

His first partnership was with Charles Wolf, but after he retired, Gustavus Bergner joined the company and it became known as the Bergner and Engel Brewing Company.

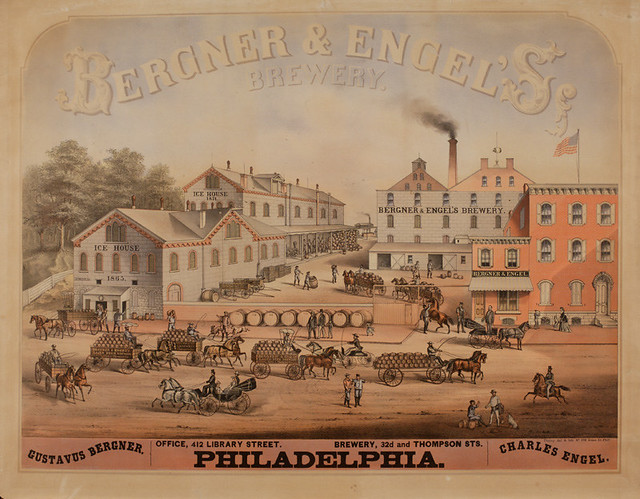

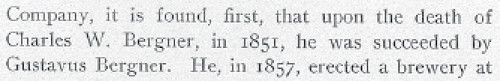

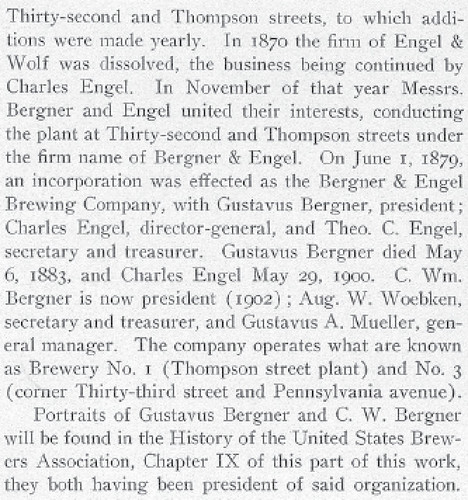

“100 Years of Brewing” also has an entry for the Bergner and Engel Brewing Company:

And this similar account is by Pennsylvania beer historian Rich Wagner:

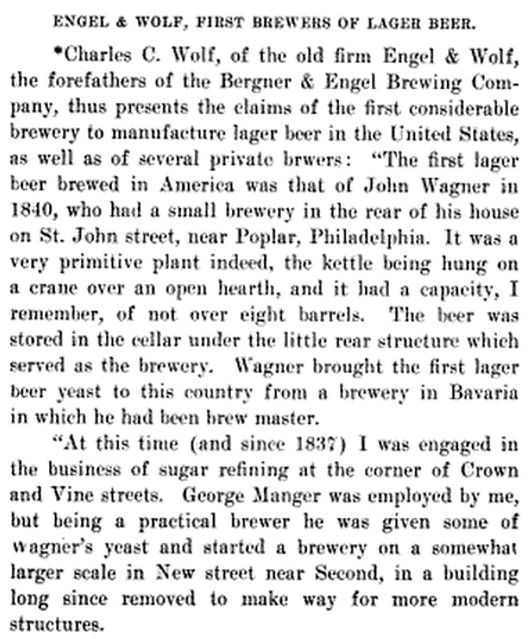

Charles Wolf, a sugar refiner in the neighborhood, had an employee named George Manger, who was a brewer by trade. Manger obtained some of the yeast and began making larger batches in a brewery on New Street near Second. Around the same time, Charles Engel, also a brewer, emigrated and found work in Wolf’s refinery. In 1844 Engel and Wolf brewed their first batch of lager beer in the sugar pan and stored it in sugar hogsheads to be shared with their friends.

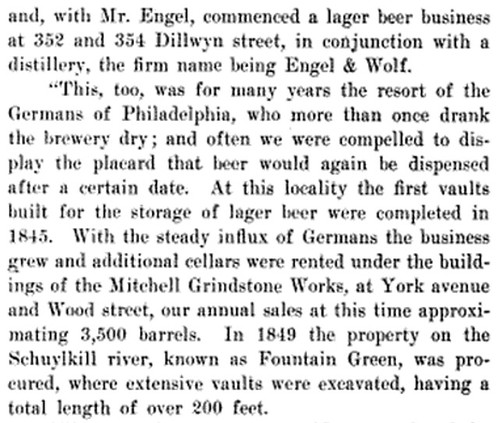

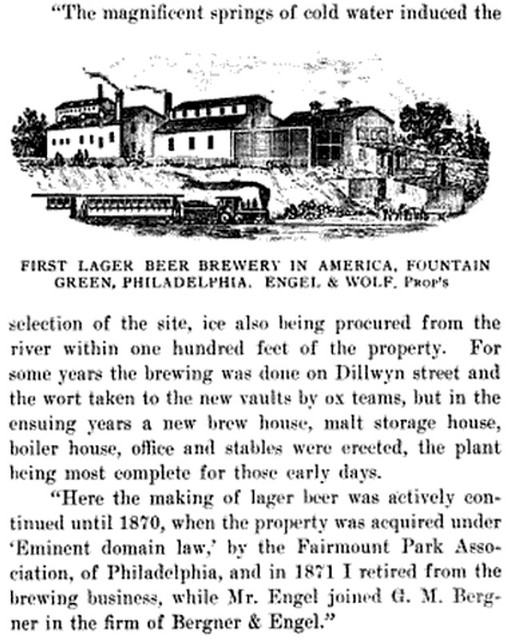

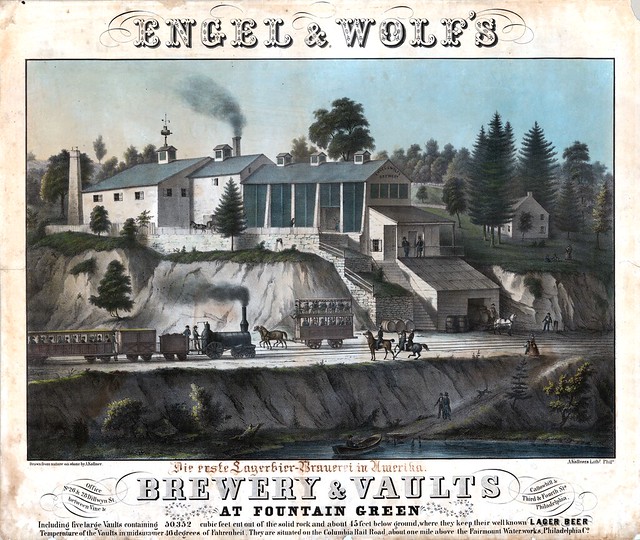

The same year, the refinery was destroyed by fire and Mr. Wolf went into the brewing and distilling business at 354 Dillwyn Street. Engel & Wolf’s brewery became a popular resort of the Germans of Philadelphia who were known to “drink the brewery dry.” Since lager yeast requires colder fermenting and aging (lagering) conditions than ale yeast, ice houses became more important than ever. Vaults were dug in 1845, and with the increasing number of German immigrants, Mr. Wolf expanded the brewery. In 1849 he purchased a property on the Schuylkill River known as Fountain Green where lager beer vaults extending over 200 feet were dug. For several years wort was hauled by ox teams from Northern Liberties to the vaults at Fountain Green, a distance of about three miles. Over the next few years a new brewery was erected on the site, modern and complete in every way. It was the first large-scale lager brewery in the United States.

Fountain Green was an ideal location. It was out in the country where there was plenty of room. There were springs on the property. Wolf’s farm was just up the road. The banks of the river are composed of Wissahickon Schist, which is fairly soft and easy to dig. In winter, being right on the river was an advantage when harvesting ice for refrigeration. In addition, the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad served the brewery with the “Engel Side” spur.

Philadelphia developed along both of it’s rivers, but along the more navigable Delaware, ship building, shad fishing, industry and commerce were most abundant. Philadelphia’s reputation as “The Workshop of the World” was earned in large part by the “river wards” of Northern Liberties, Kensington, and Frankford. These neighborhoods were literally teaming with breweries. When lager beer began to catch on, many brewers rented beer vaults along the Schuylkill River, and in the area that came to be known as Brewerytown.

Engel & Wolf enjoyed success, but in 1870 the property was acquired by the Fairmount Park Association. The city had just built the Fairmount Water Works, the most technologically sophisticated, state of the art municipal water pumping facility in the nation, and to ensure water quality, removed all industry from the Schuylkill River for a distance of five miles upstream. At this time Mr. Wolf retired and his partner joined Gustavus Bergner to create the Bergner and Engel Brewing Company.

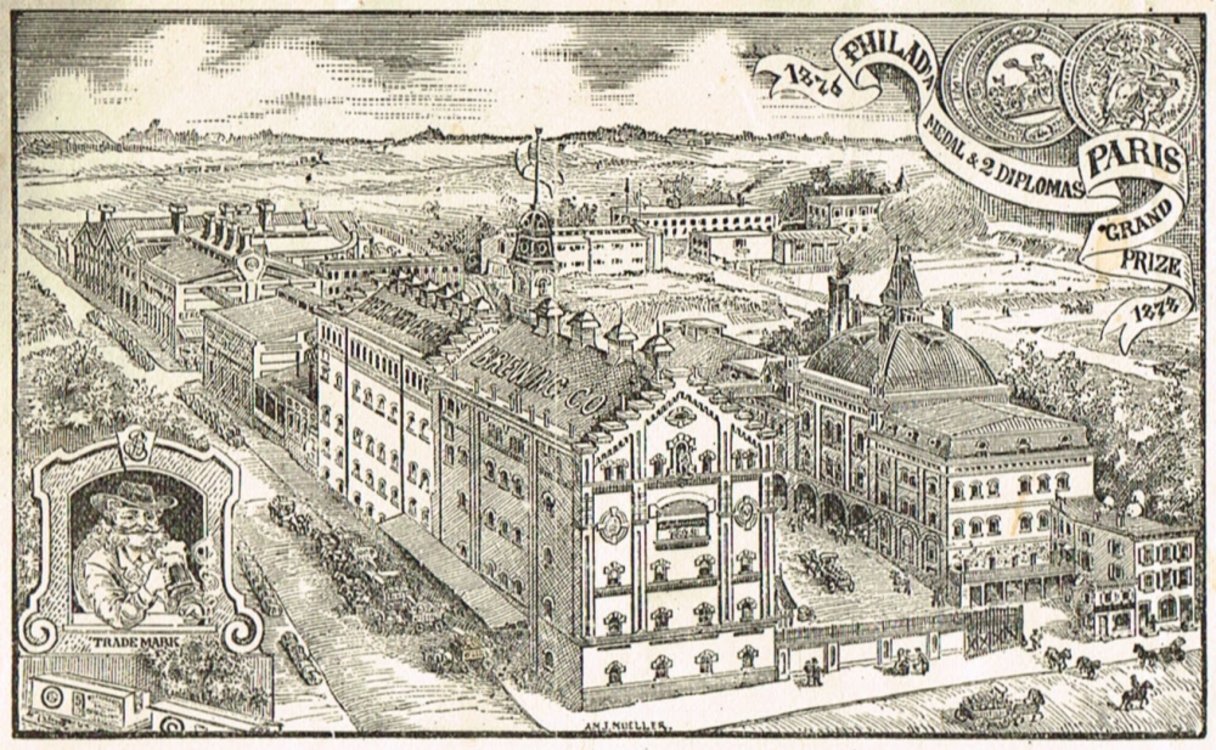

Gustavus’ father Charles had started a brewery on North Seventh Street in the Northern Liberties in 1852 which Gustavus took over upon his father’s death. In 1857, Gustavus erected a brewery at 32nd & Thompson Streets, an address that would become the heart of Brewerytown. Interestingly enough, Brewerytown was essentially up and over the river bank from the old Engel and Wolf brewery.

The earliest picture of Brewerytown that I have been able to uncover is based on four Hexamer Surveys that were made in 1868. They show thirteen breweries, one of which had a distillery, three “lager beer vaults,” including one owned by Peter Schemm, a row of dwellinghouses with beer vaults beneath them, a number of stables and at least three or four brewery saloons.

Beginning in the 1870’s ice-making and artificial refrigeration technology radically altered the equation. It made proximity to river ice of little importance. Huge fermenting and storage houses could be constructed anywhere and they could maintain cold temperatures year round. Where brewers had been bound to brew only during the colder months, it was now possible to brew year round. With the exponential increase in popularity of lager beer, artificial refrigeration was the answer to a dream.

Some brewers who had rented vaults in or near Brewerytown built breweries there. Others refrigerated their breweries and no longer needed to rent vaults. According to the list of projects executed by brewery architect Otto Wolf, the breweries were continually being altered and enlarged to accommodate the trade. The trend was for the brewers to go west to Brewerytown from the river wards, but some left Brewerytown and went into business in Kensington.

The Bergner & Engel B.C. was one of the largest brewers in the country. B & E won the Grand Prize at the Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia in 1876 and the Grand Prize at the Paris Exposition in 1878. Their beer was shipped across the country, and around the world. Gustavus Bergner was very active in the United States Brewers Association, the Philadelphia Lager Beer Brewers Association, and the Philadelphia Brewmasters Association. B & E was the largest brewer in Philadelphia, and eventually absorbed three other Brewerytown breweries: Mueller, Eble & Herter, and Rothacker.

When prohibition loomed on the horizon, Mr. Bergner had significant political clout and did everything humanly possible to prevent severe trauma to the brewing industry, not only in Philadelphia, but throughout the nation. At first, the brewers thought they would not be affected. After all, beer was hardly intoxicating when compared with liquor. Then they thought if they reduced the alcohol to 2.75% they could still sell their product. Anti-dry forces in Congress attempted to make beer available by physicians’ prescription. But in the end the Federal Government established the legal limit for “near beer” at one half of one per cent alcohol.

Prohibition devastated the brewing industry. It was such an unpopular law, that for some time, things just went on as they had before. Most of the city’s brewers were law-abiding German Americans. They could not fathom a world without a foamy seidel of beer. Not only that, but they would have to become criminals in order to make beer, their “staff of life.” Legally, they brewed “near bear,” and made soda. They made malt extract for the malt shop as well as for the home brewer, and sold yeast and ice. The Poth brewery became home to the Cereal Beverage Company, the local distributor of Anheuser-Busch’s Bevo. Due to demand and profitability, however, many continued to produce “high-octane” beer, even after being raided several times, sometimes while they were involved in litigation.

The government targeted the biggest guy on the block and made an example of B & E. After being raided, B & E continued to make beer. It was a case of the public and business community defying a terribly unpopular law and the government responded with a vengeance. And while B & E had lots of legal tricks up its sleeve, in the end the government prevailed and shut them down. Breweries throughout the city were padlocked. And in December of 1928, as police sewered nearly a million gallons of B & E beer, officers were quoted as saying “B & E made the best beer in the city.”