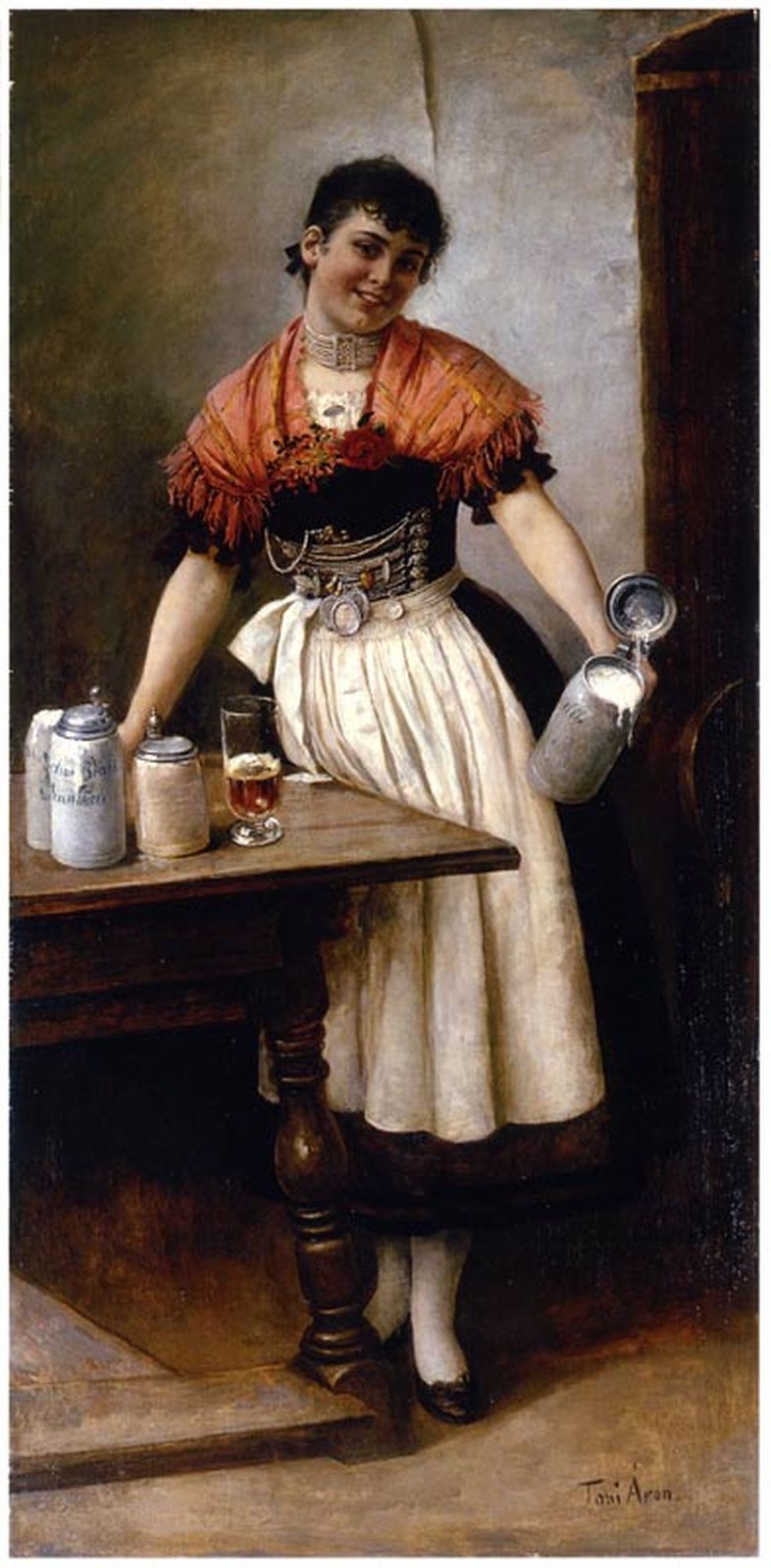

Today is the birthday of Coletta Möritz (September 19, 1860-November 30, 1953). Möritz was essentially Bavaria’s first pin-up girl, nicknamed “the beauty of Munich,” a waitress discovered by painter Friedrich August Kaulbach, who painted her on top of a barrel holding eleven mugs of beer, while instead of wearing a cap on her head, has a target instead. That’s because after doing a sketch of Möritz in 1878, when she was 18, he painted a large banner, roughly 9 x 16 feet, which hung outside a beer tent for a national shooting competition in July of 1881, in the same spot in Munich where Oktoberfest is held. The painting was called “Die Schützenliesl,” (which means “the shooting Liesl,” which was a popular German name derived from Elizabeth, or sometimes “the Marksmen’s Lisa”) and was an immediate hit. For the rest of her life — she lived to be 93 — Coletta was known as die Schützenliesl, and was also painted by other well-known artists while continuing to work as a waitress.

The Schützenliesl painting has gone on to become a Bavarian cultural symbol, used on beer labels, postcards and as a logo. In 1905, an operetta, “Die Schützenliesel,” was written by Austrian composer Edmund Eysler, with the libretto by Leo Stein and Carl Lindau.

Her story appears well-known in Germany, Austria and Eastern Europe, but much less so everywhere else. You can find it all over German websites, such as the Falk Report, Über das Leben der Münchner “Schützenliesl” Coletta, Augsburger Allgemeine, two articles on Merkur — Bavaria’s First Pin-up Girl and “I am the great-grandson of Schützenliesl” — and the Croatian Pivnica.

Here’s one of the few accounts I could find in English, from a newsletter for the German-American Society of Sarasota:

Over 150 years ago, on September 19, 1860, there was born in the village of Ebenried, Bavaria, a child who was to become one of the most admired and colorful figures in the history of Bavaria and beyond. Born Colletta Möritz, she would become “die Schützenliesl” (the Marksmen’s Lisa), beloved by all who knew her, as well as by those who knew her only through pictures of her that circulated widely. Even to this day, after she is long gone from the public scene, the well-known song “Die Schützenliesl” is played – and sung heartily.

When Colletta’s unmarried mother, Marianne Möritz, found village life too confining, she moved with her child to the capital city of Munich. As soon as Colletta grew to school age, she was given over to the poor sisters in the Au (Armen Schulschwestern) for child care and schooling. These sisters had a convent, the only one in those days where girls were trained to become teachers. Colletta yearned to become a handicraft teacher (one who would teach skills such as knitting and sewing). Her mother, meantime, became independent by opening her own second-hand shop in Munich.

As Colletta was growing up she met many Munich artists who frequented her mother’s shop, looking for old costumes to use for historical paintings or for decorating their studios. It was not just at her mother’s shop, however, where Colletta met these artists, but also at her first place of employment, where she worked as a beer hall girl. (She had failed to continue her dream of becoming a teacher because of money problems.) So by age 16 she was serving beer at the Sterneckerbräu, a popular beer hall frequented by the same artists she had seen at her mother’s shop.

The beer hall proprietor observed this new beer Mädchen and was delighted with the fact that she was such a quick learner, that she could carry 12 Maβ of beer from the basement to the Gaststube, and he noted that in spite of the hard work and menial pay, she was always cheerful. (Note: one Maβ of beer is 1 liter). Colletta was so successful at her job that she became a Kellnerin (waitress) for George Probst, who owned the Brauhauskeller. Although well known and admired, Colletta’s fame was yet to grow from these early contacts. At this point she was just a likeable and pretty beer hall girl – if unusually popular with guests.

Colletta’s world began to explode in 1881, when the 7th Deutsche Bundesschieβen was organized in Munich. A Bundesschieβen is a national shooting match, and this one became a festival of huge proportions. Marksmen from far and wide attended these shooting competitions. It so happened that one of the artists who had come to know Colletta as a beer hall girl was the famous painter Friedrich August Kaulbach. One day Kaulbach was sitting in the Sterneckerbräu tent, before the festival opened, when he suddenly had an idea – he would paint Colletta on a beer tent sign. He asked Colletta to model for him; having her hold mugs of beer in her hands and having her lift a foot as though she was dancing on a barrel. To develop the theme of the “Liesl” as a “marksmen Lisa” he added a marksman’s target to the side of her head. After he made the sketch, he took it to his studio and painted it – ready for display

Positioned on the festival field, called the Theresienwiese, were placed four beer tents (really houses), with names like “Zum wilden Jäger” (to the wild hunter), “Zum blinden Schützen” (to the blind marksman, “Zum goldenen Hirschen” (to the golden stag), and “Zur Schützenliesl” (to the marksmen Lisa). This “Gastwirtschaft” – Zur Schützenliesl – displayed prominently the Kaulbach painting. There she was, the famous Kellnerin, with her swinging skirt, and carrying 11 – not the typical 12 – overflowing mugs of Sterneckerbräu beer. The Schützenliesl, dancing on a barrel, seemed to be floating through the Bavarian beer heaven. When the Schützenfest began, hordes of people tried to get a seat in the Schützenliesl Gastwirtschaft. They wanted to sit under the Schützenliesl picture and have the real Schützenliesl bring a Maβ of beer to them. Not only did the Schützenliesl conquer the hearts of the marksmen themselves, but of all the festival visitors. Whether they were Munich natives or visitors from outside Munich, they headed for the Schützenliesl Gastwirtschaft. There the beer was flowing like a river.

Later, as an old woman, Colletta recalled, “During the whole festival, our tent was packed because everyone wanted their beer served by the Schützenliesl”. The Augsburger Abendzeitung (an Augsburg newspaper, 26 July 1881) reported on that scene: “Attached to the festival tent is the Wirtschaft to the Schützenliesl of Mr. Massinger. The idyllic tower with the red-covered roof and the stork perching on top of it would have been enough to catch the eye of those looking for a Wirtschaft. But then our F.A. Kaulbach draws a ’Liesl’ on it, one so fresh, so voluptuous, so seducing as no marksman has ever seen. It is curious but this lifeless picture seems to be the main attraction. Every nook and cranny was filled with people. One day about 8 o’clock in the evening, the proprietor raced in among the masses, pale from shock, saying that the beer supply was used up to the last drop and thousands of unfortunate beer drinkers were sitting there with their tongues drooping. After a fearful hour, only a few had left their hard-won places, the rattling of a beer wagon could be heard. The steeds raced mightily toward the tent and after a 30-minute battle, the beer was back.” According to a Munich newspaper, 16,300 Maβ of beer were drunk in the Schützenliesl Wirtschaft on the last evening of the shooting contest.

The famous Kaulbach painting of the Schützenliesl hangs today in the Festsaal of the “Münchner Haupt”, short for “Königlich privilegierte Haup.”

Here’s a translation of an article entitled “‘Schützenliesl’ is symbolic figure,” from an Exhibition of the House of Bavarian History:

In Bavaria the 19th century the inn was a place dominated by men. But what would the Bavarian festival culture without the female member? For International Women’s Day on March 08, we tell the story of Schützenliesl that it has brought to successful businesswoman and advertising icon from simple Biermadl. Even today it is a well known symbolic figure.

Coletta Möritz (1860-1953) was born near Pöttmes in Aichach-Friedberg, an illegitimate child of a small farmer’s daughter and worked after moving her mother at 16 years as Biermadl, ie auxiliary waitress at Sternecker Brau im Tal in Munich.

There perverted also members of the society of artists “tomfoolery”, among them Friedrich August Kaulbach (1850-1920), which struck the attractive beer girl. So he asked in 1878 Coletta Möritz to stand him for a sketch model. The motive of this sketch it was then that the young Coletta could be for advertising icon

The “Schützenliesl” (here a Landshuter Protect disc of 1881), a dashing beer waitress, is a popular symbol of the Bavarian festival culture. For over a hundred years, it keeps popping up in beer commercials and was immortalized in the eponymous song – an early “Wiesnhit”. Behind the legendary figure hides the waitress and hostess later Coletta Möritz (1860-1953), who came from near Pöttmes. In 1878 the young “Biermadl” was none other than the Bavarian prince and painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach model. For the VII. German federal shooting, which took place in late July 1881 the Theresienwiese, painted Kaulbach the Beautiful Coletta then as “Schützenliesl”. The colossal painting served as exterior decoration of the across Bierbude, in which the young woman also availed itself. For that time the picture was a bold presentation, it excited at the festival and beyond once a stir. Logically also be seen on the few months later bombarded memory disk Landshuter fire Schützengesellschaft that invoked the spirit of the Federal shooting again the “Schützenliesl”.

After World War 2, a German songwriter Gerhard Winkler wrote a song entitled “Schützenliesl” in 1952. It was the first post-war Oktoberfest hit and remains a staple of the songs sung in the tents during Oktoberfest. The version below is performed by Franzl Lang, and is from 1981.

Coletta was married twice, and had twelve children. She worked in restaurants and beer halls her entire life, and lived to be 93. Throughout Europe, she’s a famous figure, although especially at Oktoberfest.

Great posting, Jay. Very informative.

It warms my heart that she does not necessarily hew to today’s standards of “beauty.” So much beauty in the world, many places to find it.