Today is the birthday of Johanna Heileman (August 31, 1831-January 5, 1917). She was born in Württemberg, Germany, and married Gottlieb Heileman, who founded the G. Heileman Brewing Company in La Crosse, Wisconsin, in 1858. When her husband passed away in 1878, she became president of their brewery and she continued to run it successfully for the next 34 years, when she retired in 1912, although even then she remained on the corporate board.

Here’s a short biography of her from Find-a-Grave:

First female Chief Executive of a brewery in the United States. She was the wife of Gottlieb Heileman, founder of G. Heileman Brewing Co. of LaCrosse, Wisconsin. When he died in 1878 she became the chief executive of the company making her the first woman CEO of a brewery in the US. She also became one of the first female presidents of a United States corporation in 1890 when G. Heileman Brewing Co. was incorporated. She remained active in the company until her death.

This portrait of Johanna Heileman is from a Discover the Silent City cemetery tour by the La Crosse Historical Society:

At the age of 21, Johanna Bantle came to the United States from her home in Germany. While working as a maid in the Pabst family mansion in Milwaukee she met and married another German immigrant, Gottlieb Heileman. They eventually opened their own brewery in La Crosse, Heileman’s, and raised a family.

Gottlieb died in 1878 and Johanna was named president of the brewery. She remained the company’s president until 1912, and stayed active as a board member until her death in 1917, at the age of 85. She was one of the first female CEOs in Wisconsin history, and an upstanding figure in the La Crosse German community. Under the leadership of Johanna Heileman, the G. Heileman Brewing Company continued to grow, and more than tripled their production from the time of their opening up to 1912, becoming a leader in the industry and providing La Crosse with a successful business that brought recognition, jobs and revenue to the city.

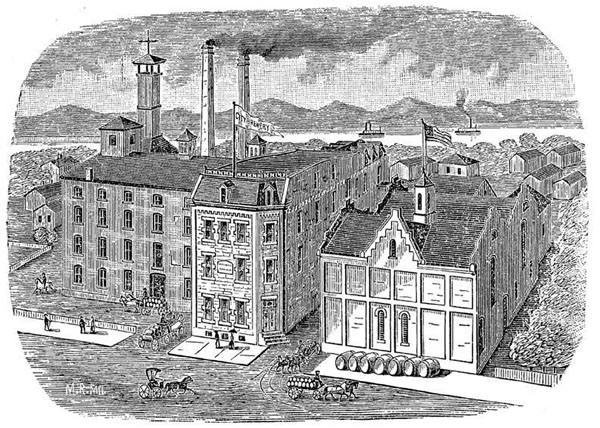

The G, Heileman Brewery in 1889.

Here’s a much more thorough account of all of the Heilemans, including Johanna, from Immigrant Entrepreneurship, entitled The Best of Partners – The Best of Rivals: Gottlieb Heileman, John Gund, and the Rise of the La Crosse Brewing Industry:

The G. Heileman Brewing Company achieved national recognition in the 1960s and 1970s when it aggressively acquired a number of well-known breweries and brands including the Blatz Brewing Company, the Rainier Brewery in Seattle, and the Grain Belt brand (now owned by August Schell Brewing Company). For much of its existence, however, the La Crosse, Wisconsin, firm operated in a conservative manner by brewing for local and regional markets only. This business strategy reflected the vision of one of the firm’s German founders, Gottlieb Heileman (born January 6, 1824, in Kirchheim unter Teck, Kingdom of Württemberg; died February 19, 1878, in La Crosse, Wisconsin), who was content to grow the firm slowly and focus on quality over quantity. John Gund (born October 3, 1830, in Schwetzingen, Grand Duchy of Baden; died May 7, 1910, in La Crosse, Wisconsin), the firm’s co-founder, eventually decided that Heileman’s business practices were too restrictive and ended the partnership in 1872 in order to build a new brewery in La Crosse that could compete with cross-state rivals such as Pabst, Schlitz, and Miller. The G. Heileman Brewing Company and the John Gund Brewing Company continued to pursue separate business strategies until national Prohibition was implemented fully in 1920. Gund’s large brewery collapsed, whereas Heileman’s smaller firm subsisted by producing non-alcoholic beer and malt products until the Twenty-First Amendment was passed in 1933.

Gund’s and Heileman’s different approaches to brewing in the post-Civil War era illustrate the diversity of business strategies employed by brewers during this period. Not all ambitious German immigrant brewers sought to create national – or even large regional – shipping breweries as did the Schlitz-Uihlein family, Adolphus Busch, and a number of other German immigrant brewers. Instead, some focused on serving local and regional markets and utilized technological advances such as artificial refrigeration and pasteurization to refine their products rather than expand their markets and market share. Furthermore, following Heileman’s death in 1878, his wife, Johanna (born August 31, 1831, in the Kingdom of Württemberg; died January 5, 1917, in La Crosse, Wisconsin), served as one of the firm’s main officers until her death in 1917. As the first known female head of a brewery in the United States and as one of the first female corporate executives in any business sector, Johanna Heileman (née Bandel) put her own unique stamp on the firm founded by her husband and his business partner.

John Gund’s vision of La Crosse emerging as the brewing center of the Midwest did not come to pass, but the city’s breweries did briefly outproduce their rivals in Milwaukee during the mid-1880s. This demonstrates that Milwaukee’s emergence as the preeminent brewing center of the Midwest was far from inevitable, and, instead, was contingent on a variety of historical factors that set it apart from other Midwestern brewery cities such as La Crosse, Minneapolis, and Duluth.

Gottlieb Heileman, Johanna Heileman, and John Gund each contributed to the development of the brewing industry in La Crosse, and any study of the G. Heileman Brewing Company’s early history must take into account the commercial, social, and cultural milieu that influenced these three immigrant entrepreneurs’ decision-making after they settled in the United States in the 1850s. Their success partially reflected the growing strength of the American brewing industry after the Civil War – made possible by the waves of German settlers who arrived in the U.S. during the mid- to late nineteenth century and who served as both producers and consumers of lager beer and other malt beverages. Nevertheless, the Heilemans and Gund were ultimately responsible for their individual successes and failures during this era as this study will demonstrate.

Family and Ethnic Background

Gottlieb Heileman (originally Gottlieb Heilemann), Johanna Bandel, and John Gund (originally Johann Gund) all hailed from the southwestern German lands. Gottlieb Heileman was one of eight children born to Caspar and Frederika Heilemann (née Meyer). He was born on January 6, 1824, in Kirchheim unter Teck, a small upland community southeast of Stuttgart in the Kingdom of Württemberg. Johanna Bandel, who also hailed from Württemberg, was born to Johann Ludwig and Kathrina Bandel (née Sigel) on August 31, 1831. She had a number of brothers who later immigrated to the United States. John Gund, on the other hand, was born approximately seventy-five miles northwest of Kirchheim in the community of Schwetzingen in the Grand Duchy of Baden on October 3, 1830. Schwetzingen lay in the rich, alluvial farmland between the Rhine and Neckar Rivers approximately six miles southwest of Heidelberg. Gund was the second of eight children born to Georg Michael and Sophia Elizabeth Gund (née Eder or Edes).

Both Heileman and Gund came from established families within their respective communities. Heileman’s father and maternal grandfather were bakers and Gottlieb Heileman received training as a baker and brewer during his youth. Gund’s father was a farmer who grew hops and tobacco, but John Gund served a two-year apprenticeship as a cooper and brewer following the end of his common school education at age fifteen. He worked an additional year as a journeyman brewer after his apprenticeship ended. The two men immigrated to the United States within four years of each other. Gund arrived in New York City in May 1848 at the age of eighteen, having traveled from Schwetzingen down the Rhine River to Rotterdam and then on to Le Havre and New York. Heileman reached Philadelphia in 1852 at the age of twenty-eight. Johanna Bandel settled in New York City in either 1852 or 1855 at the age of either twenty-one or twenty-four, respectively, and lived with her brothers for a number of years.

All three Germans followed a similar migration trajectory and made their way westward to Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin during the 1850s along with tens of thousands of other German immigrants, primarily from Baden, Württemberg, and the Palatinate. Gund’s parents settled in Freeport, Illinois, in the northwestern part of the state. John Gund found employment sixty miles to the west in Dubuque, Iowa, a commercial center situated on the west bank of the Mississippi River. He worked in a brewery operated by a German named Anton Heeb for two years. In June 1850, he relocated to nearby Galena, Illinois, to operate a brewery with a German named Witzel, possibly twenty-year-old Sebastian Witzel, who may have been an old friend. John Gund’s parents died of cholera the following month. After less than a year, he sold his share in the Galena brewery operation and rented another brewery in the community, known as the Cedar Brewery. About this time, he married fellow German immigrant Louise Hottman, a resident of Galena, with whom he eventually had five children. Two years after renting the Cedar Brewery, Gund decided to relocate to a larger and more prosperous community that would provide a better market for his beer. He and his wife moved approximately 180 miles northwest to the Mississippi River settlement of La Crosse, Wisconsin.

La Crosse had a population of approximately 2,000 residents in the mid-1850s. Situated on the east bank of the Mississippi River, the community had experienced rapid growth during the 1850s as settlers arrived to take advantage of the surrounding farmland and forests. The lumber industry flourished, facilitated by the community’s access to steamboats that plied the Mississippi River from St. Paul down to St. Louis and New Orleans. The city was incorporated in 1856 and benefitted further when a cross-state railroad connection was completed between La Crosse and Milwaukee in 1858

John Gund founded a brewery in La Crosse in August 1854. The small operation was located in a log cabin near the community’s waterfront. A number of other German immigrants founded breweries in the city in the months and years that followed. Gustavus Nicolai and Jacob Franz founded the Nicolai Brewery shortly after Gund founded his brewery. Due to production problems with Gund’s initial batch of beer, Nicolai and Franz were first to bring their beer to market. Charles and John Michel founded the La Crosse Brewery in 1857 after a failed attempt to strike it rich in the California gold fields in the early 1850s. After returning from the West Coast, they attempted to settle in Chicago but soon grew to dislike the community and made their way north to St. Paul. Ice on the Mississippi delayed their river journey and they eventually settled in La Crosse instead. After noting that existing breweries in the community could not meet local demand, they founded their own brewery.

Gottlieb Heileman reached La Crosse via Milwaukee the same year that the Nicolai brothers arrived in the city. He had worked for a year in Philadelphia after arriving in 1852. He then moved west to Milwaukee around 1854 and established a bakery with Gottlieb Maier in March 1856. The two men took out a $2,550 (approximately $70,000 in 2011$), three-year mortgage on the property, but paid off the balance within a year. Heileman was apparently less interested in baking than brewing, because he sold his share in the bakery for $1,525 (approximately $40,500 in 2011$) and moved west to La Crosse in October 1857. He found employment briefly as a foreman in the Nicolai Brewery but lost his job when Nicolai and Franz ended their partnership shortly thereafter. Heileman found a new position in the Michel brother’s La Crosse Brewery. In June 1858, he married Johanna Bandel, whom he had met during his three-year stay in Milwaukee. She had worked as a domestic servant in the midwestern city after leaving New York. Gottlieb Helieman returned to La Crosse with his bride and soon entered a new phase in his professional brewing career.

Business Development

Gottlieb Heileman and John Gund formed a partnership in November 1858 to operate the City Brewery in La Crosse. Their timing was propitious since the city of La Crosse continued to experience significant population growth, particularly among Northern European settlers, and the first outside railway connection had been completed to Milwaukee the previous month. The structures comprising the City Brewery were constructed at 1018 South Third Street. The location was south of the city’s commercial center near the Mississippi River waterfront. Early production figures for the brewery were modest. During the first decade of operation, production averaged around 500 barrels of lager beer per year (approximately 15,750 gallons). Originally, lager beer production had been limited to the winter months, but during the 1860s local brewers began using ice harvested from the Mississippi River to chill the beer during the critical lagering stage, which could last between six to eight weeks and produced a translucent and highly-carbonated final product. Heileman and Gund produced beer primarily for the local market and sold casks to hotels, taverns, and occasionally individuals. The partners constructed a hotel in downtown La Crosse in 1867 and named it the International Hotel. The facility likely offered an additional source of income for the partners and also provided a venue in which to sell their beer.

After nearly fifteen years in business together, Heileman and Gund dissolved their partnership in 1872. Heileman seems to have been content brewing beer primarily for the local market and this was reflected in the brewery’s modest output of approximately 3,000 barrels per year by the 1870s. By comparison, Eberhardt Anheuser and Adolphus Busch’s Bavarian Brewery in St. Louis produced approximately 100,000 barrels of beer per year during the same decade and the Pabst Brewery in Milwaukee produced 121,000 barrels annually. John Gund was far more ambitious than his partner and wished to establish La Crosse as a major center of brewing that would rival Milwaukee and St. Louis. Supposedly, the partners flipped a coin to determine which partner would receive the brewery and which would receive the International Hotel. Heileman won the City Brewery and Gund gained control of the hotel.

The G. Heileman Brewing Company

Gottlieb Heileman continued operating the City Brewery, now renamed the G. Heileman Brewing Company, following John Gund’s departure in 1872. The firm continued to produce a moderate volume of beer for local and regional consumption through the decade. Heileman died young in February 1878 at the age of fifty-four. Since his son, Henry, was only ten years old at the time, control of the enterprise passed to his forty-six-year-old widow, Johanna. She was assisted by Reinhard Wäcker (sometimes spelled Reinhart Wicker), who served as brewery foreman and dealt with technical matters. As president of the enterprise, Johanna Heileman became the first female head of a brewery in the United States, and after the business was incorporated in 1890, possibly the first female corporate executive in the nation. Of note, on the 1880 federal census, she listed her occupation as “keeping house,” whereas on the 1900 census she listed it as “owner of brewery.”

Other members of the Heileman family also participated in managing the business during the 1880s and 1890s. Emil Traugott Mueller, the husband of Johanna Heileman’s eldest daughter, Louisa, was hired in 1884 as a bookkeeper and assistant manager. As an adult, Henry Heileman served as vice president and assistant manager of the firm until his death from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in 1895 at the age of twenty-six.

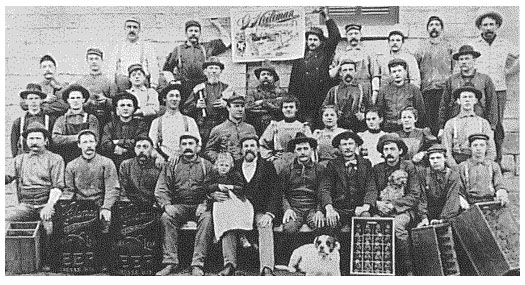

Under Johanna Heileman’s oversight, the G. Heileman Brewing Company gradually expanded its production and market reach. In 1880, the brewery produced 7,170 barrels of beer, which put it in a distant third place compared to the Gund Brewing Company and the Michel brother’s La Crosse Brewery. Five years later, the brewery produced 12,000 barrels and employed roughly thirty-five men. The firm produced a number of different beers during this period including a Vienna lager and a dark lager named Hofbrau. They also began bottling beer for regional distribution. They opened their first distribution agency in Glencoe, Minnesota, a city approximately fifty miles west of Minneapolis in 1885 and gradually expanded their reach to the Dakotas and Illinois over the next two decades. The firm also established tied houses, taverns that sold Heileman beer exclusively (i.e. they were tied to a particular producer), in various cities. One was located in downtown La Crosse and another was situated approximately thirty miles east in Cashton, Wisconsin.

The firm sought to maintain good relations with the other breweries in the community and avoid ruinous price wars. In May 1898, the major breweries of La Crosse, including Heileman, Gund, Michel, and a number of smaller facilities agreed to establish uniform prices for kegged and bottled beer. They set the rate for kegged beer at eight dollars per barrel (approximately $224 per barrel in 2011$). For bottled beer, the rate was $2.20 for two dozen quarts of export-strength lager and $1.90 for two dozen quarts of regular-strength lager. At the same time, Heileman and three other La Crosse breweries began quietly investigating the possibility of forming a trust in order to compete against Gund locally and the major Milwaukee shipping breweries regionally. The impetus for the proposed trust was Chicago accountant Otto W. Heibig. After overseeing the installation of brewing equipment at the Gund Brewery following the destructive 1897 fire, Heibig grew interested in pooling the financial resources and physical plants of the other La Crosse breweries. Heibig estimated a combined value for the Heileman, Michel, Franz Bartl, and Zeisler breweries at $930,000 (approximately $26 million dollars in 2011$). In September 1900, the brewers and Heibig filed incorporation papers for the La Crosse Brewing Company and prepared to offer $700,000 in capital stock and $500,000 in bonds. They proposed constructing a new brewery with the capacity to produce 400,000 barrels annually, which was twice Gund’s output of approximately 200,000 barrels per year. Industrial architect Otto C. Wolf of Philadelphia designed the new brewery at a proposed cost of $300,000 (approximately $8.4 million dollars in 2011$). The existing breweries of the members of the trust would be adapted to other purposes with the Heileman facility being converted into a malting plant and the other breweries becoming storehouses and a dedicated ale brewery. Despite the great potential of the project, it never progressed beyond the planning stages. Shortly after the trust was incorporated in September 1900, a brewer in Cincinnati purchased the equipment intended for the proposed facility in La Crosse. The following January, the trust announced its new slate of corporate officers, which included Emil T. Mueller of the G. Heileman Brewing Company as treasurer. Little further action occurred over the next two years and eventually the trust collapsed in 1902, apparently due to resistance from officials at the Heileman Brewery.

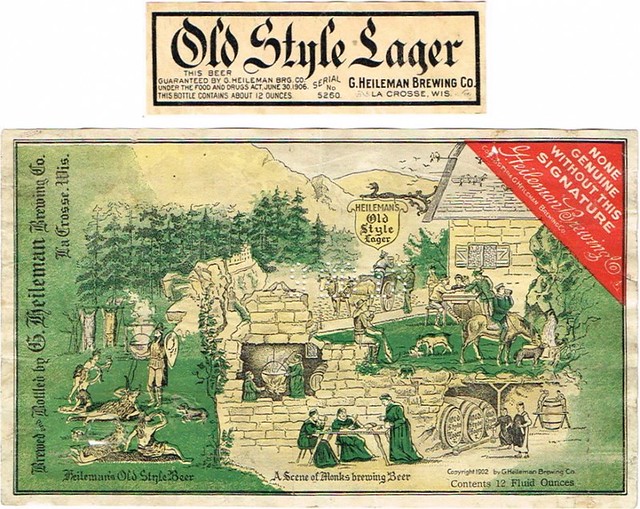

During the first decade of the twentieth century, G. Heileman Brewing introduced their best-known beer brand and went through a reorganization. The firm had acquired the trademark for a light lager, Golden Leaf, from a Milwaukee brewery in 1899 and a year later introduced a new heavier lager, Old Times Lager. In 1902, they renamed the beer Old Style Lager following a complaint from another brewery producing a similarly named beer. They also ended production of Golden Leaf to free up capacity for Old Style, which the firm produced exclusively in bottled format, as it was intended for distribution to regional markets. Emil T. Mueller played a key role in promoting the beer brand extensively over the following decade. Johanna Heilemann and the other brewery executives also expanded the firm’s capitalization to $350,000 from the original capitalization of $75,000 and used the funds to increase production to approximately 175,000 barrels per year. The firm’s brewery workers organized themselves around the same time and the firm signed a contract with Local 81 of the International Brotherhood of Brewery Workers, thus avoiding labor conflict.

By the 1910s, Heileman was shipping cases of bottled Old Style Lager to thirty-four states and had entered the lucrative Chicago market with more than fifty saloons and a number of distribution agents. Firm president Johanna Heileman passed away in January 1917, setting in motion a gradual transition from family to professional management at the firm. Johanna Heileman’s son-in-law, Emil T. Mueller, assumed the presidency of the firm, a position he held until his death in 1929. After Mueller died, another son-in-law, George Zeisler Jr., took over as president of G. Heileman Brewing until 1933, when the firm was reincorporated and non-family members assumed the presidency and key positions on the board of directors.

Unlike Gund Brewing, Heileman weathered the storm of Prohibition. Rather than risk producing low alcohol beer in 1919 and 1920, the firm began brewing a new, non-alcoholic beer called New Style Lager in May 1919 when the Wartime Prohibition Act went into effect. Like other breweries around the nation, the firm also produced a variety of hopped malt syrups and extracts that could be used by home brewers to produce beer and a line of soft drinks. Such measures helped the firm eke out an existence during the 1920s and early 1930s. In 1931, a major fire destroyed a number of warehouses and nearly bankrupted the firm, since the brewery had not insured the structures. Brewery officials warned that the firm was unlikely to survive much longer given the prohibition on alcohol sales and the general business disruption caused by the Great Depression. Fortunately, the gradual repeal of Prohibition beginning on April 7, 1933, gave G. Heileman Brewing a second lease on life. In the weeks leading up to April 7, the firm began brewing 3.2 percent beer permitted under the repeal act around the clock and released truck- and trainloads of the beer shortly after midnight on the seventh. Demand was so great that the firm could not fill all its orders and was forced to return numerous checks uncashed. Following the firm’s reincorporation, professional managers sought to update the brewery’s physical plant, improve quality control, which had slipped during the 1930s and 1940s, and expand production and distribution. This process continued into the 1950s and 1960s.

Personality and Social Standing

Both the Gund and Heileman families participated in the German institutions of La Crosse, Wisconsin, as well as in the local and regional brewing community. Little information survives about their specific involvement in the secular and religious institutions of La Crosse, but records show that John Gund’s eldest son, George, was a member of the local Turnverein in the 1870s. The physical education society had its origins in the post-Napoleonic German lands and was first introduced unsuccessfully to the United States in the 1820s. German 48rs reintroduced the Turner movement at the end of the 1840s and within a few years, Turner societies had emerged in major American cities with German populations. The La Crosse Turnverein was organized in October 1855 and John Gund granted the group permission to practice in the yard of his small brewery in 1856. They may have continued using the space through 1858, when Gund sold the property following his partnership with Heileman.

Gund and Heileman were members of the Lutheran Church and Heileman’s 1878 funeral at the local Lutheran church in La Crosse was considered to be one of the largest funerals in the history of the city to that date. More than 160 carriages belonging to mourners participated in the funeral procession from the church to the nearby Oak Grove Cemetery. Six prominent brewers in the community served as Heileman’s pallbearers, however, John Gund was not among them. This may have reflected lingering animosity between the former partners. When Gund died in 1910, members of the local Liederkranz Society, which was affiliated with the Turnverein as part of the local Deutscher Verein von La Crosse, attended his funeral along with members of the Brewer’s Union.

Politically, John Gund’s party affiliation reflected broader shifts in German immigrant political participation during the second half of the nineteenth century. He supported the Whig ticket shortly after his arrival in the United States and voted Republican in the 1860s and 1870s, but his allegiance shifted to the Democratic Party in his later years. This may have been linked to the Democrats’ opposition to the growing prohibitionist movement in the United States and the support they enjoyed from populist, agrarian elements in Midwestern states like Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa. No information exists on Gottlieb Heileman’s political views.

Networks

Members of both families were active in professional and personal networks of largely German-American composition both at the local and national levels. These networks often overlapped, particularly in the case of marriage. John Gund’s nineteen-year-old daughter, Louisa, married La Crosse brewer Charles Michel in 1872. This cemented a bond between the two families who operated the largest and second largest breweries in La Crosse, respectively, throughout the closing decades of the nineteenth century. Similarly, Gottlieb and Johanna Heileman’s daughters married men who would later play key roles in the management of their family firm in the twentieth century.

Family members also participated in professional associations related to the brewing industry. The Heileman family joined the United States Brewers’ Association in 1886 and members of the Gund family participated in the association’s lobbying efforts on behalf of the American brewing industry. The Heileman’s son-in-law, Emil T. Mueller, served as secretary of the Personal Liberty League’s La Crosse chapter. Supported by the U.S. Brewer’s Association, the League lobbied against prohibitionist policies at the local and state levels and worked to protect the business interests of breweries in Wisconsin and elsewhere.

Lastly, family members were active in local civic associations and enterprises in La Crosse. John Gund’s eldest son, George, served on the city’s Board of Trade as its first treasurer. Later, he was selected as president of the La Crosse Baseball Association in the late 1880s. He was also among the original investors in the city’s Street Railway Company in 1879, a position that gave him influence over the city’s economic development.

Immigrant Entrepreneurship

John Gund and Gottlieb and Johanna Heileman participated in the introduction of European lager beer and German beer culture to the United States in the middle of the nineteenth century. They initially served kegged beer to a largely German local clientele. Advertisements for their products appeared in German in local periodicals such as the Nord Stern. Labels for their early bottled products also contained German phrases and in the Heileman’s case listed the producer as “Heilemann City Brauerei.” Over time, though, John Gund and later Johanna Heileman expanded the scope of their respective breweries’ operations in order to provide bottled beer to a broader, regional consumer market that was less directly tied to German ethnicity. Their success in the lucrative Chicago market through tied houses helped to make both Peerless and Old Style well known among regional beer brands, and their advertising and bottle art embraced European iconography but typically avoided explicitly German references.

John Gund and Gottlieb Heileman acquired knowledge and experience in German brewing practices through apprenticeships, and they brought this knowledge with them to the United States. Both men entered the brewing trade on a limited scale after they immigrated and settled in the Midwest. No evidence exists that either man received remittances from family members in the German lands, so they likely had to accumulate slowly the necessary capital in order to open their brewery in 1858. Gund worked in a number of breweries in Iowa and Illinois before moving to La Crosse. Similarly, Heileman worked as a baker in Milwaukee before gaining experience as a foreman at two breweries in La Crosse. Once the partners founded the City Brewery, they pursued a conservative business strategy and likely reinvested their profits in the operation. Rather than trying to grow the business quickly and expand into distant markets, they found plenty of consumers in La Crosse and its hinterlands during the 1860s and 1870s.

Gund returned to Germany in 1873, shortly after he ended his partnership with Heileman. The purpose of the visit was social, but it is likely that he also surveyed the brewing landscape in Germany and brought back knowledge with him that he employed in founding the John Gund Brewery. It is unknown if Heileman returned to German at any point before his death in 1878.

Conclusion

The firms founded by German immigrants John Gund and Gottlieb Heileman reflected the broader fate of the American brewing industry in the twentieth century. Like hundreds of other breweries, the John Gund Brewing Company did not survive Prohibition. The family shut down the operation and eventually sold off the firm’s assets piecemeal over the next two decades. G. Heileman Brewing survived the turmoil of Prohibition and its professional managers eventually determined that the firm had to expand or fall victim to industry consolidation in the 1960s. Consequently, the corporation purchased breweries across the nation during the 1970s, while also fending off challenges from the other major brewing firms of the era, including Pabst, Miller, and Anheuser-Busch. At the same time, publicly-traded Heileman stock became a target for speculators. The firm fended off hostile takeover attempts successfully in the 1980s, but eventually sunk into bankruptcy and was acquired by Stroh in 1996.

La Crosse, Wisconsin, failed to emerge as a major center of brewing comparable to Milwaukee. It simply lacked the population and financial resources of its cross-state rival. By the beginning of the 1960s, Heileman was the only brewery left in the city, whereas Milwaukee was home to major national shipping breweries including Miller, Pabst, and Schlitz. These firms had the financial resources that Heileman lacked and were better able to weather the storm of industry consolidation in the 1970s.

Over multiple generations, the Gund and Heileman families left their mark on the economic and physical landscape of La Crosse. Both Heileman and Gund’s names remain part of the city fabric. One of the old Gund Brewery buildings now houses loft apartments and the former G. Heileman Brewery is currently operated as a contract brewery for a number of brands. Surrounded by busy brewery buildings, Gottlieb and Johanna Heileman’s large brick home still reflects the conservative values of the company’s German immigrant founder.

John Gund and Gottlieb Heileman found success by selling beer to their fellow immigrants. Over time, this success translated into greater business opportunities. Though neither firm exists today, both left a legacy that is felt within the local La Crosse community and the national brewing industry.