Here’s an interesting historical piece, from 1819-20. It was a four-volume set of books known as “Remarkable Persons,” though its full title was “Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters of Remarkable Persons From the Revolution in 1688 to the End of the Reign of King George II” and was subtitled “Collected from the most authentic accounts extant.” The full collection is available digitally at the Villanova University’s Farley Memorial Library, who describes the work as follows:

This collection contains the four volumes of: Portaits, memoirs, and characters, of remarkable persons: from the revolution in 1688 to the end of the reign of George II collected from the most authentic accounts extant by James Caulfield. “Caulfield’s ‘remarkable characters’ are persons famous for their eccentricity, immorality, dishonesty, and so forth.” — Dict. nat. biog. This work contains 155 engraved plates including work by engravers: George Cruikshank, W. Maddocks, Henry B. Cook, Robert Graves, and Gerard van der Gucht.

Another sources claims that it was a “collection of portraits and stories about the eccentrics of Britain in the 18th century by James Caulfield was issued by subscription in 1819 and 1820 to great success. It promised to satisfy the public fascination with ‘true stories’ about exceptional feats, physical peculiarities and notorious acts. The extent to which it actually contained ‘true stories’ is a matter for conjecture.” The one that caught my eye was a 19th century publican.

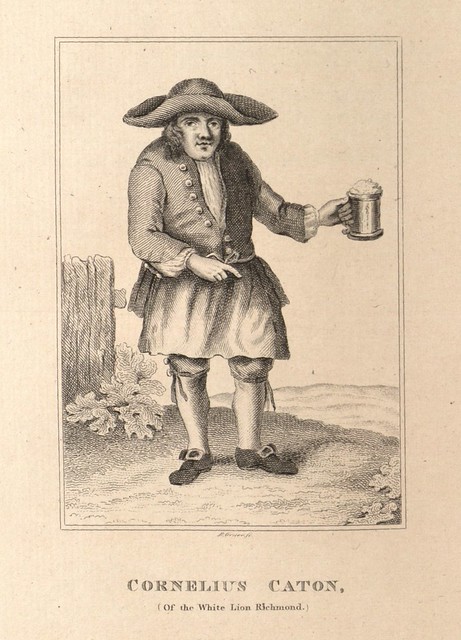

Plate 19 in Volume 3 depicts “Cornelius Caton, (Of the White Lion Richmond),” followed by his story on pages 173 through 175. Here’s his colorful story:

This little whimsical publican, having passed through the several gradations of pot-boy, , helper in the stables, and other menial offices attached to a public inn, at length rose to the important place of principal waiter: being of a complaisant temper, and possessing a species of low wit and pleasantry, he rendered himself so acceptable to the humour of the different guests which frequented the house, as to derive considerable perquisites from his ready desire to serve and accomodate the various description of persons whom business or pleasure drew to the place.

Caton carefully treasured up the money he obtained from time to time; until he had saved a sufficient sum to enable him to take the White-Lion public-house, at Richmond, in Surrey. The drollery of the landlord brought him considerable custom, which his attention to business so far improved as to make his house the most frequented of any in Richmond; and he became a general favourite with most of the inhabitants.

In person, he was one of the most grotesque appearance; and might have gained a livelihood bu exhibiting himself as a dwarf; this, joined with a certain oddity of manner, rendered him so conspicuous a character, as to bring him into great notice; and Cornelius Caton, and his house, found visitors from most parts of the adjacent villages in the neighbourhood.

He was well known to many persons in London; and, among others, George Bickham, the engraver, who deemed him of sufficient importance to speculate on engraving and publishing his portrait. This did not tend to diminish the number of Caton’s friends: and many have made a journey from town to Richmond, merely from curiosity of seeing the landlord of the White Lion.

A few years since, an equally singular personage, named Davis, a true son of Sir John Barleycorn, kept the Load-of-Hay public-house, on Haverstock-hill, near Hampstead; the eccentricity of whose personal appearance brought a considerable number of persons, particularly on a Sunday afternoon, and made the house a place of great trade.

Cornelius Caton was living at the time of his present majesty’s ascension to the throne, but the print of him was engraved in the reign of King George the Second.

You can see the original pages at Villanova digitalLibrary. Click on Volume 3 and scroll down to just before page 173, which is Plate 19.