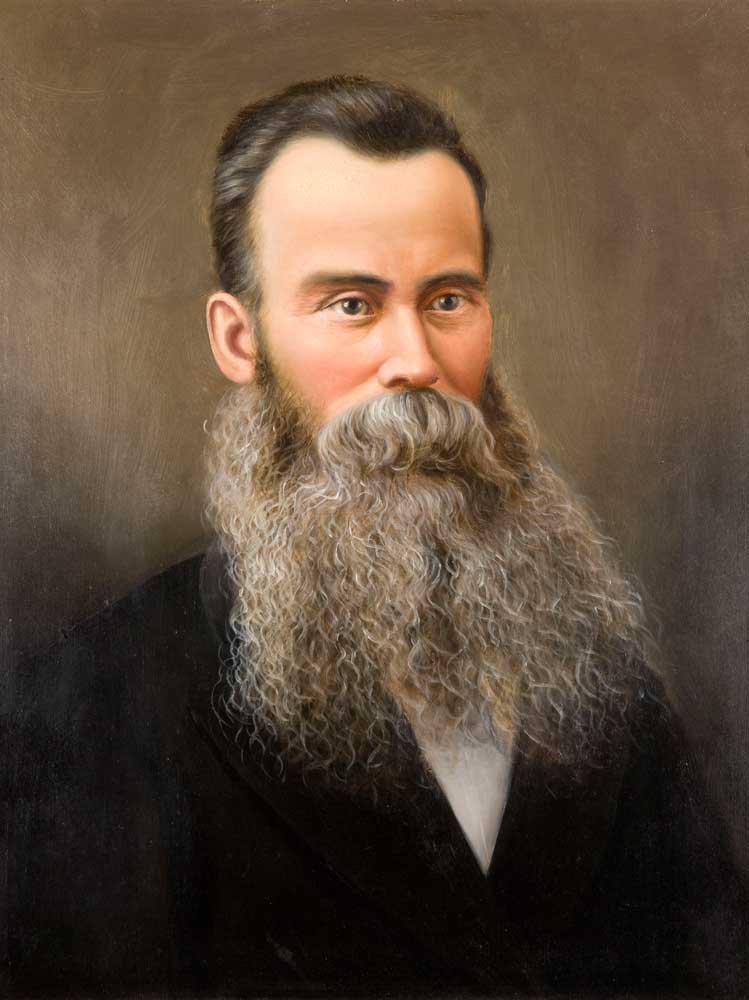

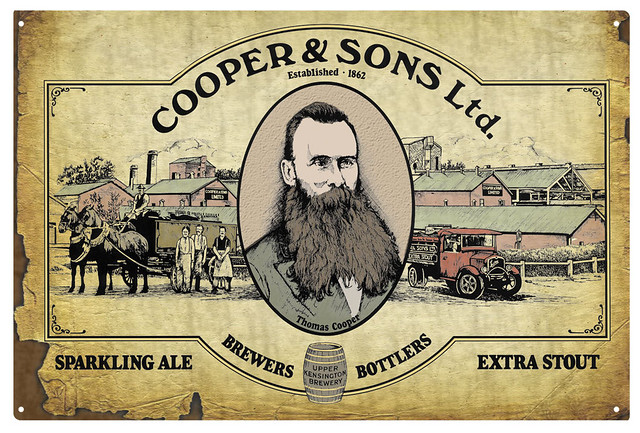

Today is the birthday of Thomas Cooper (December 17, 1826-December 30, 1897). He was born in England, but moved to Australia when he was 26. He initially worked a variety of jobs, but in 1862 founded the brewery known today as Coopers Brewery “at his home in the Adelaide suburb of Norwood. He brewed his first recorded batch on 13 May 1862.”

This biography of Cooper is from the Cooper Brewery Wikipedia page:

[He] was born in Carleton, North Yorkshire, the youngest of 12 children of Christopher and Sarah (née Booth). His parents died when he was young (Sarah in 1830 and Christopher in 1832), and he was raised by his sister Ann. Thomas was apprenticed to a shoe-maker, and by the late 1840s, six of the seven living children had moved to Skipton. John, a shuttlemaker, lived in Bradford; Jane and Mary married; Ann was a housekeeper; Elizabeth and Martha were domestic servants.

In 1849 he married Ann Laycock Brown (1827–1872) in the Wesleyan Chapel in Skipton. Their first child, William (1850–1882), was born in 1850, and Sarah Ann (1851–1852) in 1851. In 1852, Thomas, the pregnant Ann, and their two children emigrated to South Australia, setting sail from Plymouth on the SS Omega on 29 May 1852. During the 86-day voyage, Sarah Ann was one of the six children who died, but their third child was born as they rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and was named Sarah Ann (1852–1854) in memory of her sister. The family arrived in Port Adelaide on 24 August 1852. Their first home was a rented two-room cottage near the Rising Sun Inn on Bridge Street in the then village of Kensington, about three miles east of the city. In the ten years before he commenced brewing in Norwood, Thomas worked initially as a shoemaker, then as a mason, and then as a dairyman, while Ann bore four more children: Mary Ann (1855–1856); John Thomas (1857–1935); Christopher (1859–1910); and Annie Elizabeth (1861–1921). In 1856 he purchased land in George Street, Norwood, and using his new skills as a mason, built a house which he described to his brother as having “6 rooms & Cellar & Passage” and 12 ft ceilings “on acct of Sumr heat”. In the same letter, and many others, he urged his brother and family to join him in South Australia, but this never eventuated.

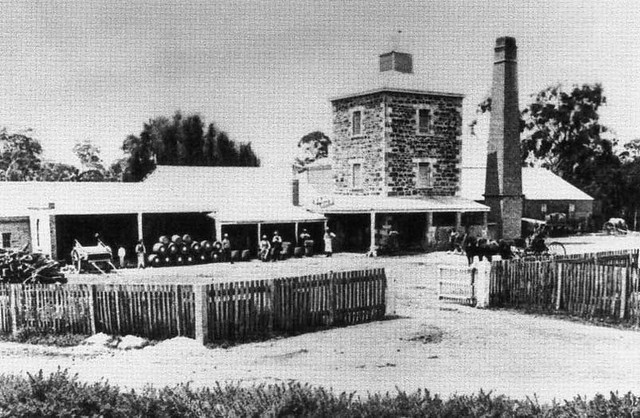

On 13 May 1862, Thomas brewed his first recorded batch. He did all the work himself (purchasing, calling for orders, brewing, washing, filling, corking and wiring the bottles, delivering the finished product), possibly with the help of then 12-year-old son William, while continuing to attend the cows, run the dairy, and do the daily milk deliveries. Being unlicensed, in early June he sought “professional advice on the sale of beer” from a solicitor, which his ledger records as having cost 7s 6d. Towards the end of 1862 Thomas realised that to make a living as a brewer, he would need to increase his brewing capacity, so he mortgaged his property to Frederick Scarfe, the Mayor of Norwood, a butcher, and a customer of Thomas’s ale, for £300, and built a new brewhouse. In January 1863 he sold his cows and the milk delivery run. Although with half-a-dozen breweries in Adelaide, there was a lot of competition, Thomas’s ale was unique in that he used no sugar, “consequently, ours being pure, the Doctors recommend it to their patients”. Although one of the smaller South Australian brewers, Thomas gained a reputation for quality. By 1867 he had over 120 customers, some quite notable (e.g. Samuel Davenport, John Barton Hack, George Hawker, Dr Penfold and the Lord Bishop of Adelaide, but he did not supply public houses, “apparently because it was against his principles”.

Ann bore four more children before dying suddenly in 1872: Joseph Brown (1863–1888); Jane Amelia (1865–1943); Margaret Alice (1868–1869) and Samuel (1871–1921). She was survived by all five of her sons, and two of her six daughters.

Thomas remarried in 1874, and Sarah Louisa Perry bore eight children: Stanley Reasey (1875–1938); Thomas Perry (1876–1876); Francis Scowby (1877–1878) Frederic (1878–1952); Edward Booth (1880–1881); Charles Edward (1881–1936); Lily Louise (1881–1893); and Walter Astley (1882–1909).

When he died in 1897, Thomas was survived by his wife, and nine of his nineteen children – seven of his sons, and two of his daughters.

This story is of Coopers’ beginnings is from the brewery website:

When Thomas Cooper used an old family recipe to brew his first batch of ale back in 1862, it would be fair to describe him as a novice craft brewer. Apparently he’d only intended it to be a tonic for his sick wife, but the resulting ale was so flavoursome that friends and neighbours soon came to appreciate it for more than just its ‘restorative’ properties. As demand for his naturally conditioned ales grew throughout the fledgling colony of South Australia, Thomas Cooper’s growing passion for brewing soon became his profession.

Before Thomas passed away, he handed over the reigns of the brewery to four of his sons, and so began a proud family tradition that has continued in an unbroken chain of six generations, for more than 150 years. While we’re still using Thomas Cooper’s original recipe, successive generations of Coopers have made improvements along the way.

The fusion of traditional Coopers brewing methods with cutting edge production technology has helped us grow our capacity and deliver consistent brew quality and flavour. As a result, we now have the ability to produce our naturally conditioned ales and stouts for a global audience, with absolute confidence that whenever one of our signature beers is poured, the drinker will enjoy a quality Coopers brew. This marriage of century-old brewing techniques and modern innovation is what makes Coopers unique in Australia’s brewing landscape.

This more modern history is by Martin Wooster, which was part of a longer travel piece he did for All About Beer in 2000 about Australian breweries, entitled “In the Shadows of Giants:”

The brewery that has done the most to provide Australians with choice and diversity is Coopers of Adelaide. But even when given clear directions, it’s a hard brewery to find. It’s quietly nestled in the shady Adelaide suburb of Leabrook, hidden beneath towering jacaranda and lilly pilly trees. For a brewery that’s been making beer on its site for over 100 years, it’s an amazingly quiet place.

The Coopers story begins in 1862, when Thomas Cooper, a British emigrant, decided to make some ale to help his ailing wife Ann deal with a fever. Ann Cooper came from a brewing family, and Thomas Cooper used her recipe. In south Australia’s relatively hot climate, Cooper had to adapt the British recipe, making his ale bottle conditioned to last longer and adding sugar to spark the secondary fermentation. The result was a style known as “sparkling ale.”

Cooper then followed with Coopers Extra Stout. Like the ale, the stout is bottle conditioned and can age for a long time. The Lord Nelson Hotel in Sydney serves five-year-old Coopers Extra Stout⎯when it mellows and develops port-like notes.

Thomas and Ann Cooper had 10 children; when she died in 1874, Thomas Cooper married Sarah Perry and had 10 more children. Eleven of these children survived into adulthood, ensuring that there were lots of Coopers to continue the family name. Coopers is the only Australian brewery controlled by descendants of its founder. “We wouldn’t want to be the generation that sold the brewery,” says marketing director Glenn Cooper.

Like most family-owned breweries, Coopers has gone through hard times. Coopers refused to adapt to changing times; it did not make lager until 1968, and until 1982, secondary fermentation for its ale and stout still took place in giant wooden casks called “puncheons.” While many younger drinkers thought that the cloudy beers were something only grandpa drank, Coopers stubbornly stuck to its traditional ways. The result was that, even when Australian beer was at its blandest, consumers knew that a good beer didn’t have to be a lager.

Coopers paved the way for us,” said Blair Hayden, managing director of the Lord Nelson Hotel, Sydney’s only brewpub. “It showed Australians that there was something else to drink besides lagers.”

What saved Coopers was homebrewers. Homebrewing was legalized in Australia in 1973, and Coopers at first sold sacks of wort that could be fermented with the addition of yeast. But customers found the sacks cumbersome, so in 1977 Coopers was the first brewery to market malt extracts for homebrewers. Coopers engineers also built the canning equipment needed to mass produce the extracts, and created a special lid to ensure that the Coopers yeast packets were securely fastened to the cans.

According to Glenn Cooper, Coopers currently has 35 percent of the world market for homebrew kits and 80 percent of the Australian market. Sales, he says, are largest in countries with high beer taxes, such as Canada and the Scandinavian nations.

In the 1990s, Coopers has diversified into many other areas. In the early 1990s, it began to enter the honey business through its Leabrook Farms subsidiary. Why honey? “Like malt extract, it’s a heavy, viscous substance,” Glenn Cooper said. Another Coopers division makes gourmet vinegars.The core of Coopers business remains its beers. Under the leadership of head of brewing operations Tim Cooper (who abandoned a career as a cardiologist to work in the family brewery), Coopers now has 10 beers, adding several filtered beers and a dark ale to its portfolio. In 1998, the company released Extra Strong Vintage Ale, the first vintage-dated beer ever issued in Australia. Production of the ale, which is designed to age for up to 18 months, is limited to 25,000 cases, for sale only in Australia.

Production, Glenn Cooper says, is increasing by 18 percent a year. And Coopers beers are becoming more available in America. They are available in most Outback Steakhouses, and, repackaged under the Old Australia label, are also sold in most Trader Joe’s stores.

This statue of Thomas Cooper is at the side of the Coopers Brewery today.