Our 56th Session is a nod of the head, acknowledging the positive aspects of the big, multinational brewers that we so often admonish and criticize. Our host, Reuben Gray at Tale of the Ale, calls his topic Thanks to the Big Boys, which he describes as follows:

What I’m looking for is this. Most of us that write about beer do so with the small independent brewery in mind. Often it is along the lines of Micro brew = Good and Macro brew, anything brewed by the large multinationals is evil and should be destroyed. Well I don’t agree with that, though there may be some that are a little evil….

Anyway I want people to pick a large brewery or corporation that owns a lot of breweries. There are many to chose from. Give thanks to them for something they have done. Maybe they produce a beer you do actually like. Maybe they do great things for the cause of beer in general even if their beer is bland and tasteless but enjoyed by millions every day.

While I don’t necessarily like most of the products made by the remaining larger brewers, what they do make is incredibly difficult to brew consistently. They have perfected the science side of brewing, however in doing so I believe they have lost a lot of the artistic side of the equation. To me the best beers contain an equal mix of both the brewer’s art and science. Craft brewers are the modern alchemists, turning base materials into liquid gold. One of alchemy’s goals was to find an “elixir of life.” In craft beer’s innovation, creativity, diversity; ultimately producing a panoply of flavorful beer, I don’t think it’s a stretch to suggest they have found that mythic elixir.

But the science that the big brewers bring to to the table is, at least in part, what allowed the new generation of brewers to — as Sam Calagione is fond of saying — “let their freak flag fly.” From the dawn of the industrial revolution, all of the big brewers (which, for the most part, was ALL of them) introduced innovation after innovation into the brewing process. Refrigeration became commonplace. Thanks to Pasteur, yeast was finally understood and could be controlled. Industrialization allowed for so many advancements into the process that an ancient brewer would hardly recognize one today. From the mid-1800s to the present, brewing has changed more than in the thousands of year before that time. And for that, we can thank all of the big breweries who invested heavily in improving the way their beer was made. R&D suddenly became a much bigger part of an operating brewery, and the trade literature of that time is crammed full of one latest innovation after another.

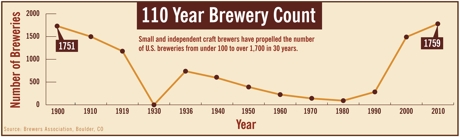

In fact, the breweries that innovated better than their competitors and adapted to the new technologies began to dominate the beer industry. While there were certainly other factors at work, it does partly explain the sharp drop in the number of breweries in America which peaked around 1873 with 4,131. After the decade of the 1870s, improved efficiencies in the brewhouse meant that breweries could serve a wider geographic territory and the more successful started swallowing up the weaker. By 1900, the number of breweries was below 1,800.

For the next century, both before Prohibition and then after (ignoring that blip of re-openings in 1933) the number of operating breweries continued to fall until around 1980, when thanks to the new microbrewery revolution they began to rise once more. By that time it was less about efficiencies and more about the bigger trying to squelch the competition. Maybe it had always been strictly about “business,” but in the 1970s and 80s it seemed more more ugly, at least to me, as I watched one regional brewery after another close all around me.

But for their part, the remaining companies did keep the history of beer alive, with many having extensive libraries, collections of breweriana and a desire to celebrate the fact that the had survived at least up to that point. By the time I joined the beer industry in some fashion, and was no longer a civilian, there were only three really big brewers, and few more remaining regionals. Like the old nursery rhyme, Ten Little Indians, “then there were three.” The Big 3, as they were often referred to. It seemed like there would always be the Big 3. I was a surprised as anyone when Coors and Miller decided to merge their U.S. operations. “Three little Injuns out on a canoe, One tumbled overboard and then there were two.” I rarely hear anyone refer to the remaining ABI and MillerCoors as the Big 2, now they’re just the big brewers. And Pabst could easily become another third, if only they’d just buy their own brewery and become a legitimate player.

So I think we have much to thank the big boys for, from the science and modern technology they embraced to their reluctant role as the keepers of brewing history. Not to mention that they could easily have stopped the legal change that gave a tax break to small brewers way back when. It was certainly within their political clout to kill it, but they worked with the small brewers instead. Whether it was because they didn’t consider them a threat or whether they genuinely welcomed them into their fraternity it unclear, but doesn’t really matter in the end.

One thing many beer geeks, I think, don’t realize is that there are many, many really good people working at the big breweries. We spend so much energy criticizing their products, their advertising, their marketing, their toxic and often bullying practices, that many people overlook that fact. The big breweries are alike with the small ones insofar as the entire industry is comprised of a nearly universal group of good people, certainly a cut above any other I’ve worked in or knew people who did. And the beer business is a people business, as much as it’s about anything else. So while I may not raise a toast to everything they do, and I may not use one of their beers for that toast, I will very much raise a toast to the people, and especially the brewers, that comprise the largest segment of the beer industry: the big boys. This one’s for you.

Thanks Jay