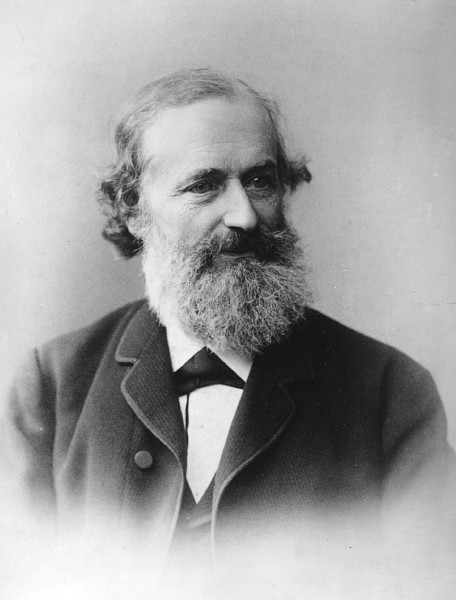

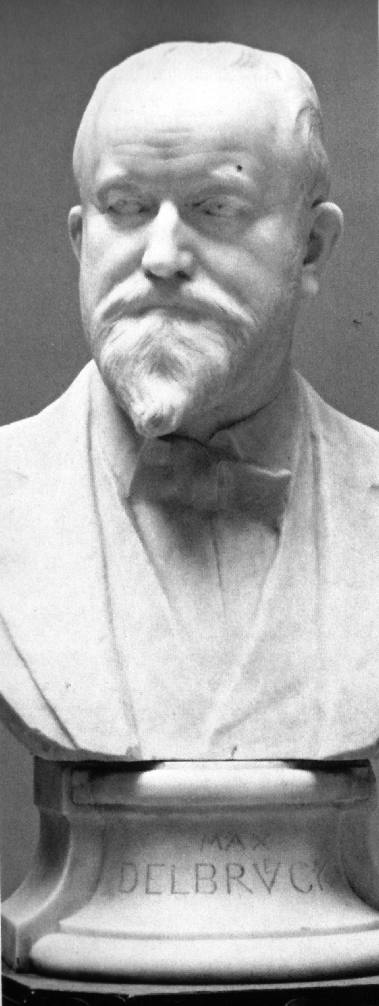

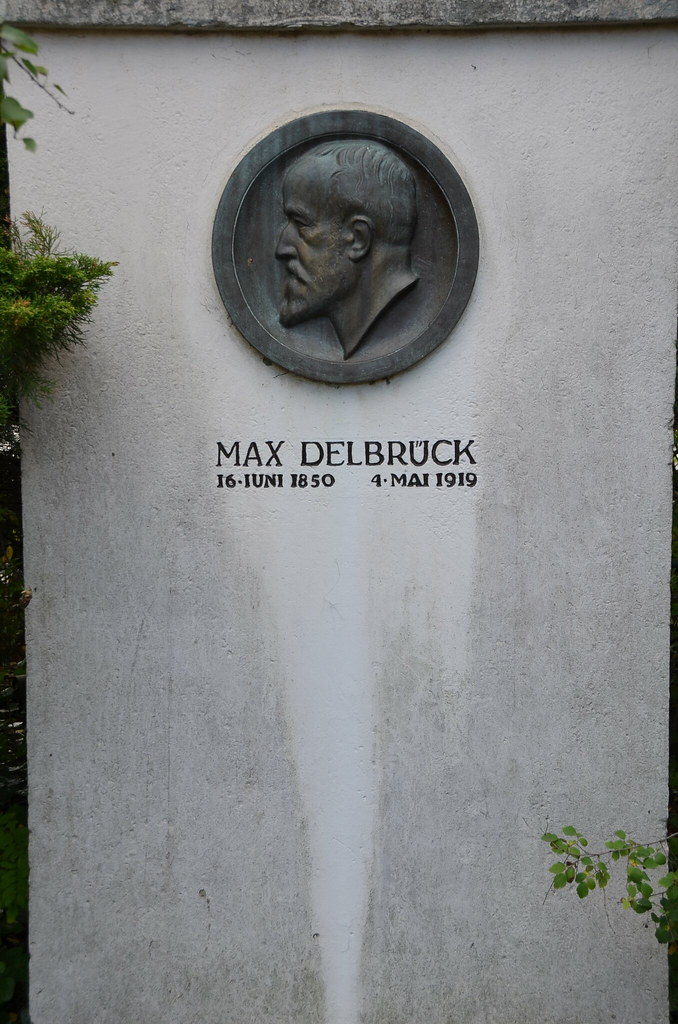

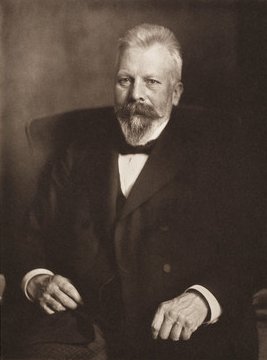

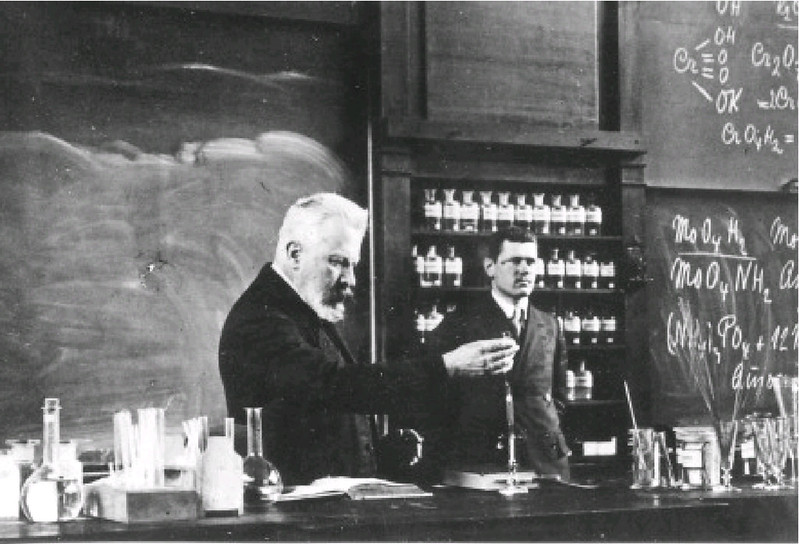

Today is the birthday of Max Emil Julius Delbrück (June 16, 1850-May 4, 1919). He was a German chemist who spent most of his career exploring the fermentation sciences.

His Wikipedia entry is short:

Delbrück was born in Bergen auf Rügen. He studied chemistry in Berlin and in Greifswald. In 1872 he was made assistant at the Academy of Trades in Berlin; in 1887 he was appointed instructor at the Agricultural College, and in 1899 was given a full professorship. The researches, carried out in part by Delbrück himself, in part under his guidance, resulted in technical contributions of the highest value to the fermentation industries. He was one of the editors of the Zeitschrift für Spiritusindustrie (1867), and of the Wochenschrift für Brauerei. He died in Berlin, aged 68.

And here’s his entry from Today in Science:

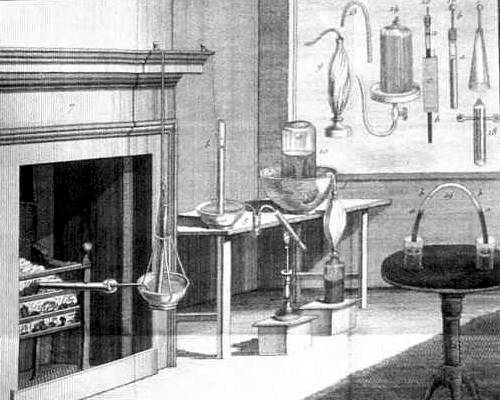

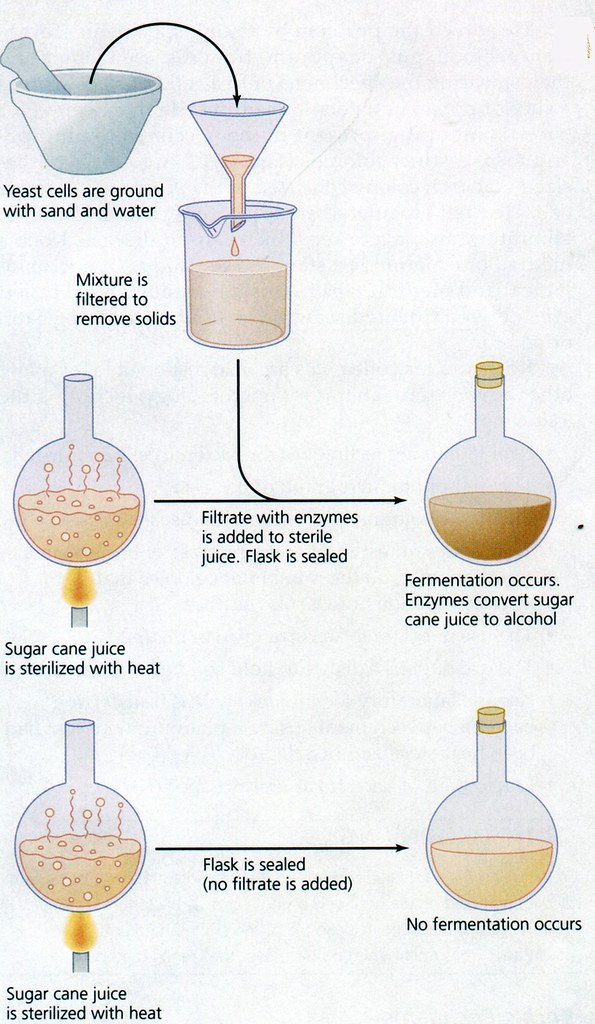

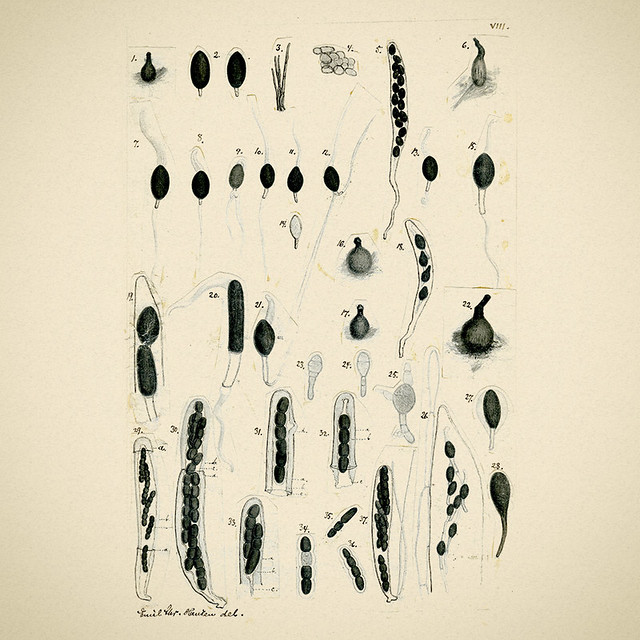

Max Emil Julius Delbrück was a German chemist who spent a forty-five year career leading development in the fermentation industry. He established a school for distillation workers, a glass factory for the manufacture of reliable apparatus and instruments, and an experimental distillery. Giving attention to the raw resources, he founded teaching and experimental institutions to improve cultivation of potatoes and hops. He researched physiology of yeast and application in the process of fermentation, production of pure cultures, and the action of enzymes. He started the journals Zeitschrift fur Spiritus-Industrie (1867) and Wochenschrift für Brauerei, for the alcohol and brewery industries, which he co-edited.

Over the years, I’ve found a few great Delbrück quotes:

“Yeast is a machine.”

— Max Delbrück, from an 1884 lecture

“With the sword of science and the armor of Practice, German beer will encircle the world.”

— Max Delbrück, from an address about yeast and fermentation in the

brewery, to the German Brewing Congress as Director of the Experimental

and Teaching Institute for Brewing in Berlin, June 1884

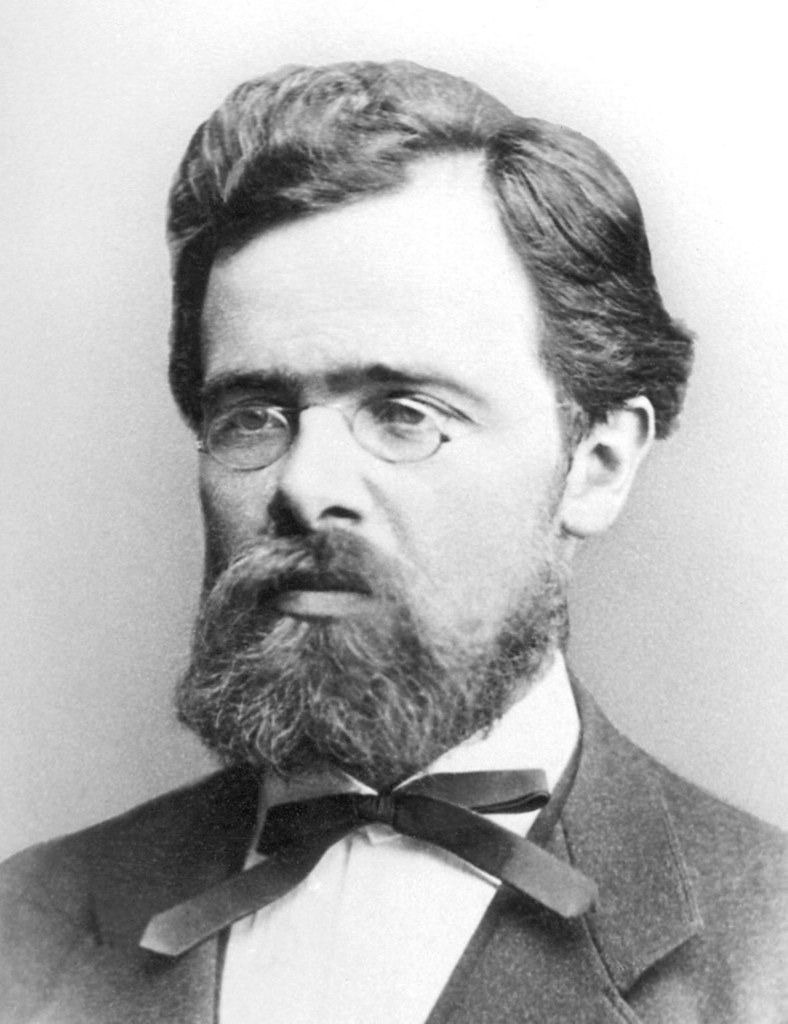

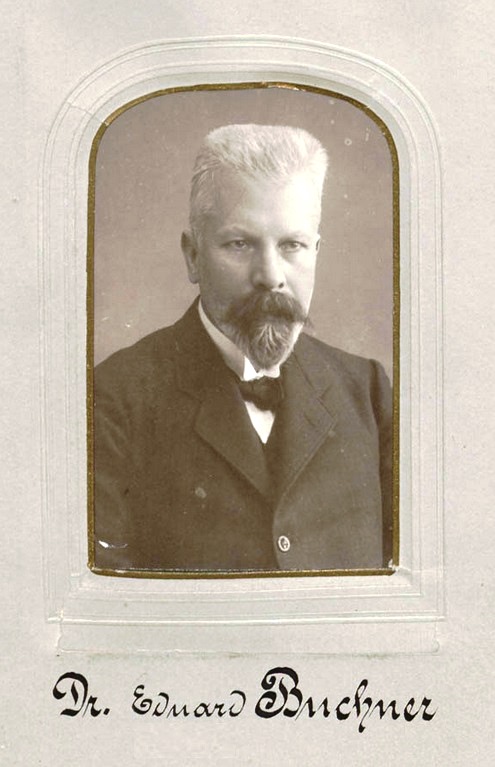

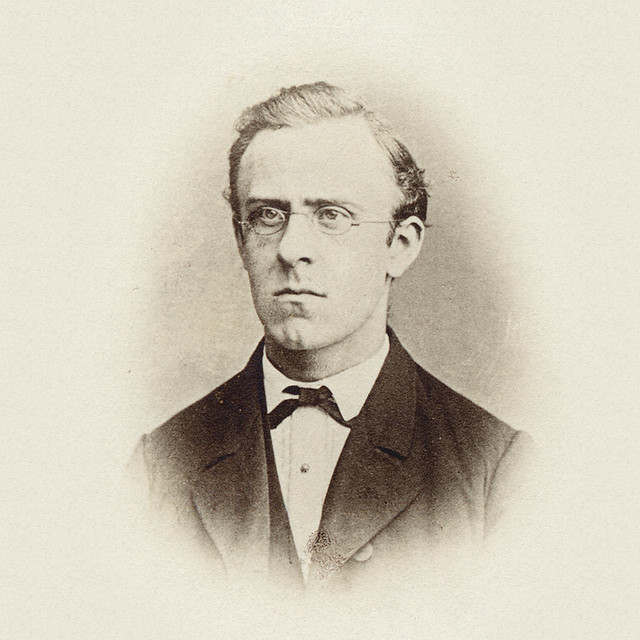

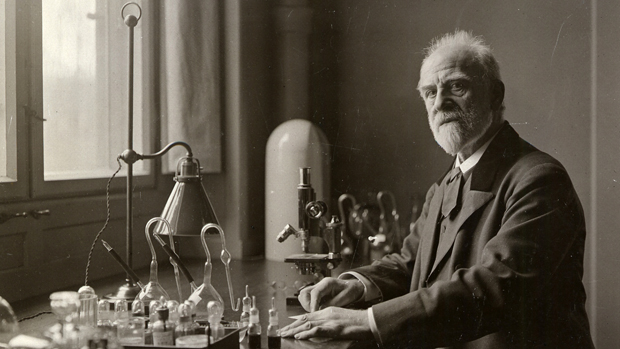

Emil Christian Hansen, taken in 1908, a year before his death.

Emil Christian Hansen, taken in 1908, a year before his death.