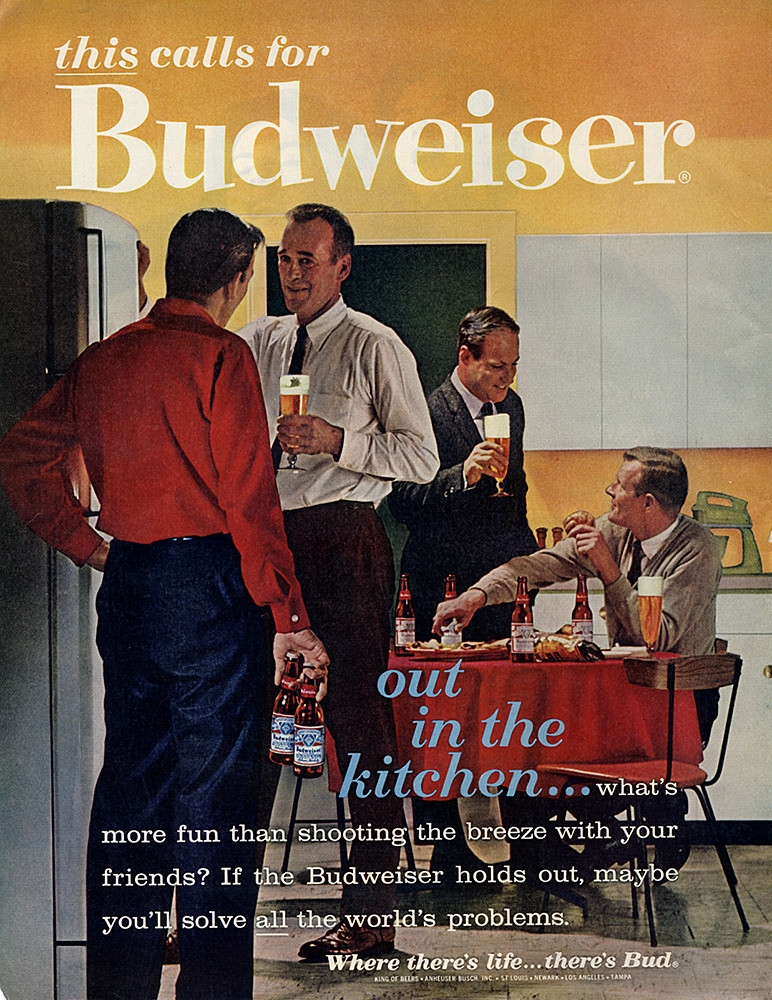

Friday’s ad is for “Budweiser,” from the early 1960s. This ad was made for Anheuser-Busch, and was part of their series using the tagline “this calls for Budweiser,” which ran during the 1960s, and replaced the earlier “Where there’s Bud” campaign. This one features a weekly guy’s night out for bowling, which was incredibly common at this time. The text begins “bowling night….”