![]()

It’s hard to believe the Bulletin has been going for over ten years, just over eleven to be exact (not including on the family blog from a couple of years before that). But this post is from exactly ten years ago, in 2007, and I was reminded of it yesterday when a homebrew blogger linked to it in a discussion of hop utilization. Anyway, it was interesting to see again, and since it was exactly a decade, I thought I’d post Hunt’s Hop Tea again. It is, coincidentally, National Hot Tea Day today. Enjoy.

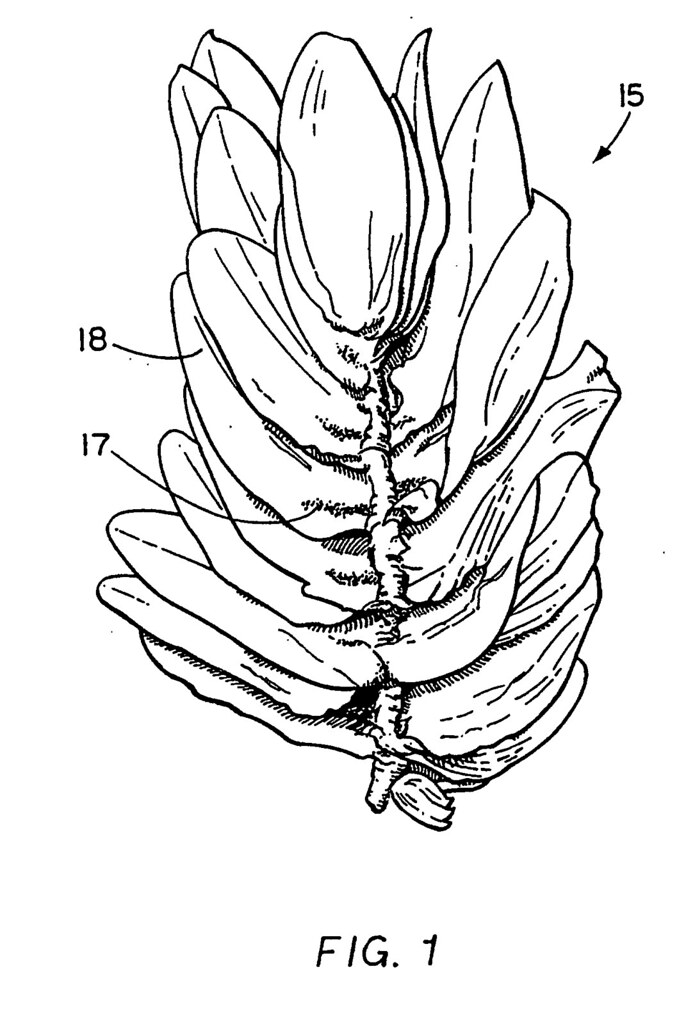

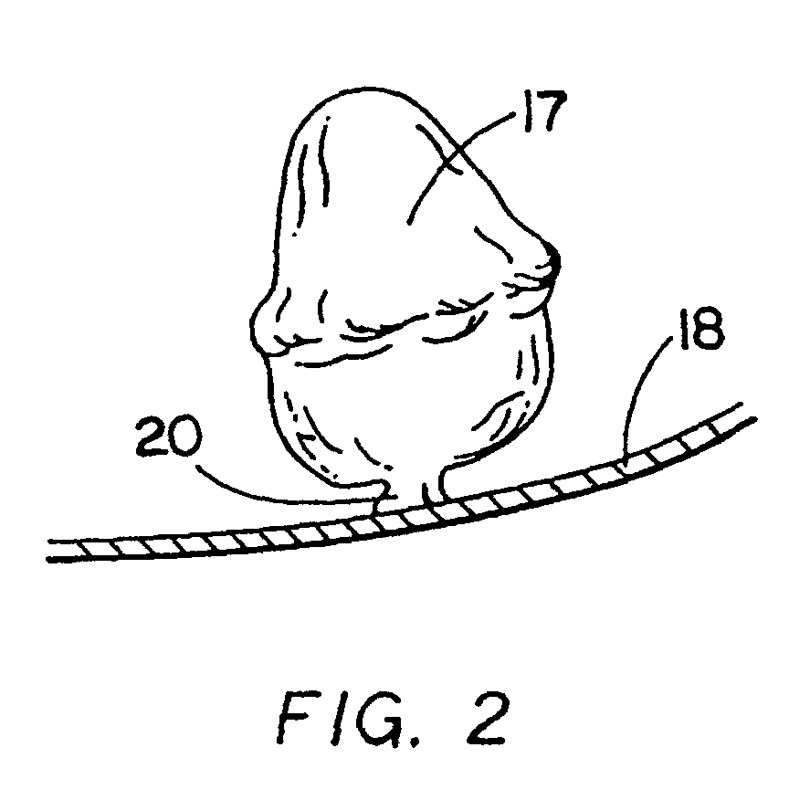

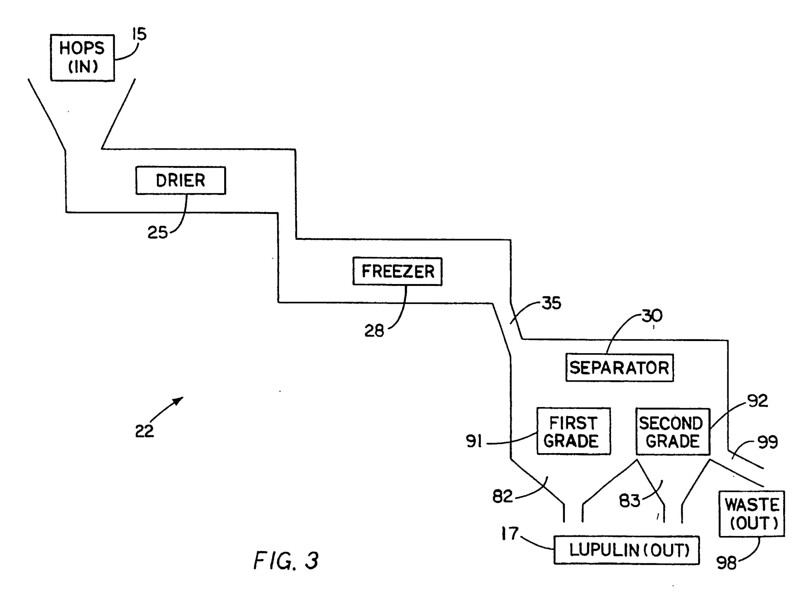

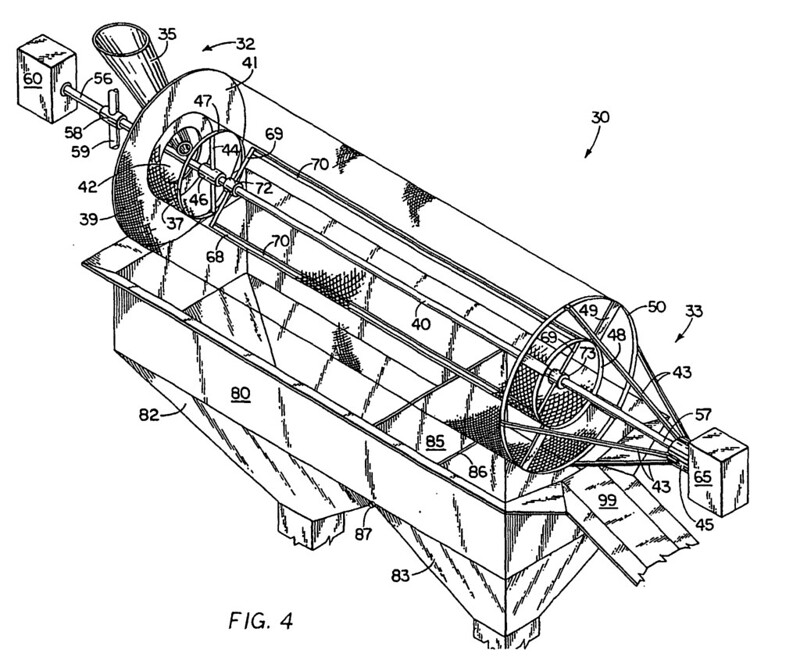

A few weeks ago while helping Moonlight with their hop harvest, owner/brewer Brian Hunt broke out something I’d never seen before: hop tea. Now I’ve seen regular hop tea before, I’ve even bought some at the health food store and tried it, but this was something totally different. Brian told me the idea grew out of an experiment he was doing to see how hops reacted at different temperatures, which he presented at “Hop School” a few years ago. He discovered in the process that he could make a delicious hop tea and that it varied widely depending on the temperature of the water. Here’s how it works:

- Put approximately two-dozen fresh hop cones in a 16 oz. mason jar.

- Heat water to __X__ temperature.

- Fill jar with heated water and seal cap.

- Let the water come down to ambient room temperature.

- Refrigerate.

- Drink.

There appears to be four main factors that change depending on the temperature of the water. These are:

- Color

- Float

- Bitterness

- Tannins

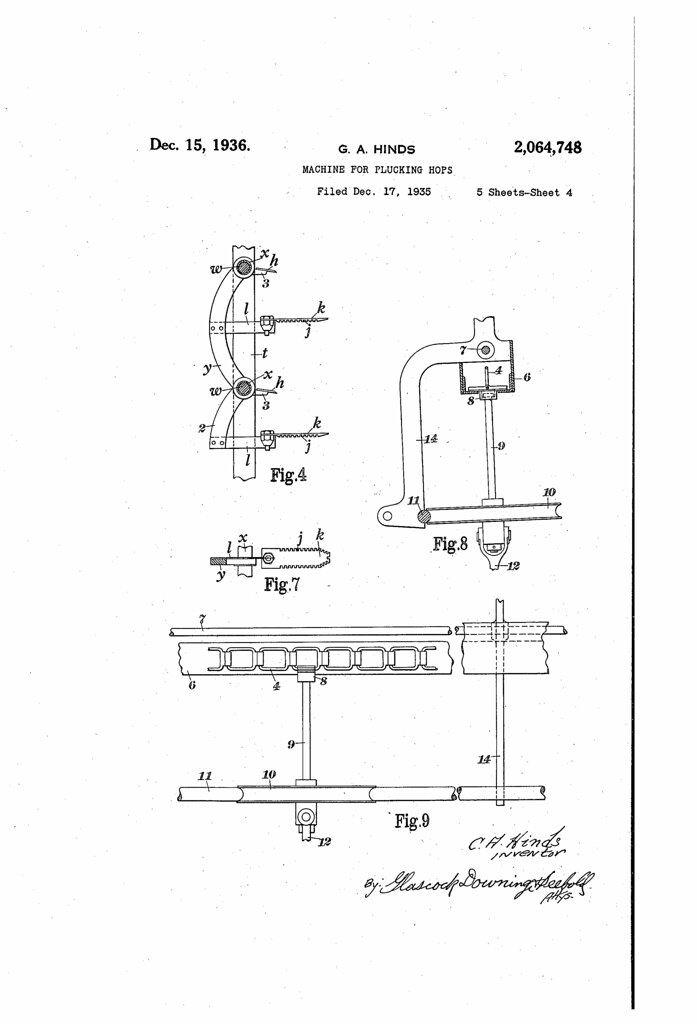

Intrigued by all of this and quite curious, Brian brought out seven examples of his hop tea made with water of different temperatures: 60°, 120°, 130°, 140°, 160°, 180° and 185°. They’re shown above from lower to higher temperature, left to right.

As you can see, the lower the temperature, the more green the hops are and the water remains less cloudy. At the higher temperatures, the hops are stripped of their green, becoming brown, and the water also becomes more brown. Also, as the temperature increases, the hops lose their buoyancy and begin to sink in the water. Although you can’t see it in the photo, the hotter the water, the more hop bitterness and at the upper range, tannins begin to emerge. Here’s what I found:

- 60°: Fresh, herbal aromas with some hop flavors, but it’s light.

- 120°: Bigger aromas, less green more vegetal flavors.

- 130°: Also big aromas emerging, flavors beginning to become stronger, too, but still refreshingly light.

- 140°: More pickled, vinegary aroma, no longer subtle with biting hop character and strong flavors.

- 160°: Very big hop aromas with strong hop flavors, too, with a touch of sweetness. Tannins are becoming evident but are still restrained.

- 180°: Big hop and vinegary aromas, with flavors becoming too astringent and tannins becoming overpowering.

- 185°: Vinegary aromas, way too bitter and tannins still overpowering.

Trying each of the tea samples with Tim Clifford, now owner of Sante Adairius.

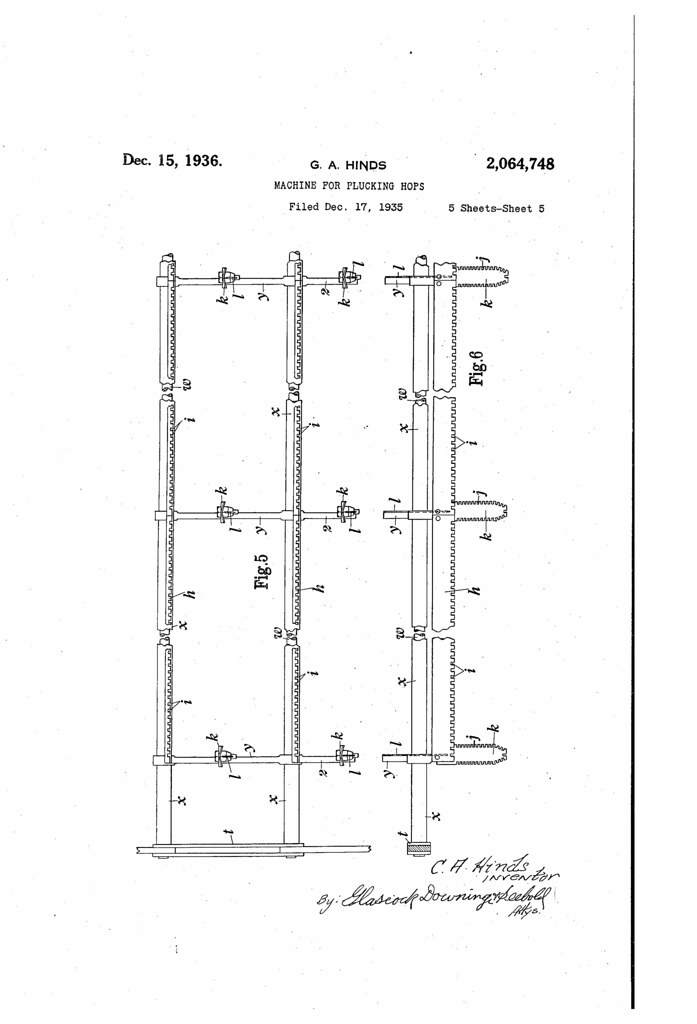

Brian was kind enough to let me take a small bag of fresh hops with me so I could recreate his experiment at home. I had enough for four samples and made tea at 100°, 140° and 160°. Using two dozen hop cones made the jars look light so I used three-dozen in the last jar, also using 160° water. I tasted them with my wife, hoping to get a civilian opinion, too. Here’s what we found:

- 100°: Hops still green and floating. The nose was very vegetal and reminded my wife of the water leftover in the pot after you’ve steamed vegetables like broccoli or Brussels sprouts. The mouthfeel is somewhat gritty with light, refreshing flavors and only a little bitterness, which dissipates quickly.

- 140°: Hops turned brown, but still floating. Light hop aromas with some smokey, roasted aromas and even a hint of caramel. Fresh hop flavors with a clean finish. My wife, however, made that puckering bitter face signaling she found it repugnant.

- 160°: Hops turned brown, but most has sunk to the bottom of the jar. Strong hop aromas and few negatives, at least from my point of view. My wife was still making that face, cursing me for dragging her into this. Hop bitterness had become more pronounced and tannins were now evident, with a lingering finish.

- 160° Plus: This sample had 50% more hops. The hops had also turned brown but, curiously, they were still floating. The nose was vegetal with string hop aromas. With a gritty mouthfeel, the flavors were even more bitter covering the tannins just slightly, but they were still apparent, and the finish lingered bitterly.

It seems like either 140° or 160° is the right temperature. Lower than that and you don’t get enough hop character (I’m sure that’s why the hops remain green) but above that the tannins become too pronounced. It appears you have to already like big hop flavor or you’ll hate hop tea. I found it pretty enjoyable and even refreshing though it’s still probably best in small amounts. You do seem to catch a little buzz off of it, which doesn’t hurt. I’m sure the amount of hops is important and more research may be needed on that front. Brian tells me that hop pellets can also be used though I doubt the jar of tea looks as attractive using them. They have the advantage of being available year-round, of course. If you use pellets, you need only about a half-ounce for each pint jar.

If you try to make Hunt’s Hop Tea on your own, please let me know your results. And please do raise a toast to Brian Hunt’s ingenuity.