Today was a dark day in a certain part of London, known as the Parish of St. Giles. On October 17, 1814, an incident which became known as the London Beer Flood took place. Here’s the basic account, from Wikipedia:

At the Meux and Company Brewery on Tottenham Court Road, a huge vat containing over 135,000 imperial gallons (610,000 L) of beer ruptured, causing other vats in the same building to succumb in a domino effect. As a result, more than 323,000 imperial gallons (1,470,000 L) of beer burst out and gushed into the streets. The wave of beer destroyed two homes and crumbled the wall of the Tavistock Arms Pub, trapping teenage employee Eleanor Cooper under the rubble. Within minutes neighbouring George Street and New Street were swamped with alcohol, killing a mother and daughter who were taking tea, and surging through a room of people gathered for a wake.

One source claimed this engraving appeared shortly after the incident, an artists rendition, so to speak, but I’ve since learned it very recent, created by a London artist, Chris Bianchi, for Completely London, and given the title “It’ll All End in Beer.”

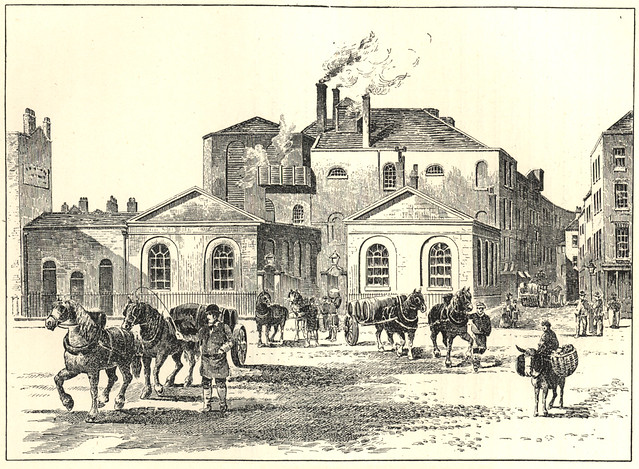

The flood occurred at Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd., which was established in 1764, It was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. Meux, like many modern brewers, bought out smaller breweries. One of the breweries it acquired was the Horse Shoe Brewery (founded by a Mr Blackburn, and famous for its ‘black beer’), located on the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street, London. Atop the Horse Shoe stood several large vats of beer. The largest was the porter vat – a 22-foot-high monstrosity that held 511,920 litres of beer, in turn held together by a total of 29 large iron hoops. For some idea of its vastness, The Times report of 1 April, 1785 read:

There is a cask now building at Messrs. Meux & Co.’s brewery…the size of which exceeds all credibility, being designed to hold 20,000 barrels of porter; the whole expense attending the same will be upwards of £10,000.

Meux’s Horse Shoe Brewery, c. 1830.

The following account of the incident is from Historic UK:

On Monday 17th October 1814, a terrible disaster claimed the lives of at least 8 people in St Giles, London. A bizarre industrial accident resulted in the release of a beer tsunami onto the streets around Tottenham Court Road.

The Horse Shoe Brewery stood at the corner of Great Russell Street and Tottenham Court Road. In 1810 the brewery, Meux and Company, had had a 22 foot high wooden fermentation tank installed on the premises. Held together with massive iron rings, this huge vat held the equivalent of over 3,500 barrels of brown porter ale, a beer not unlike stout.

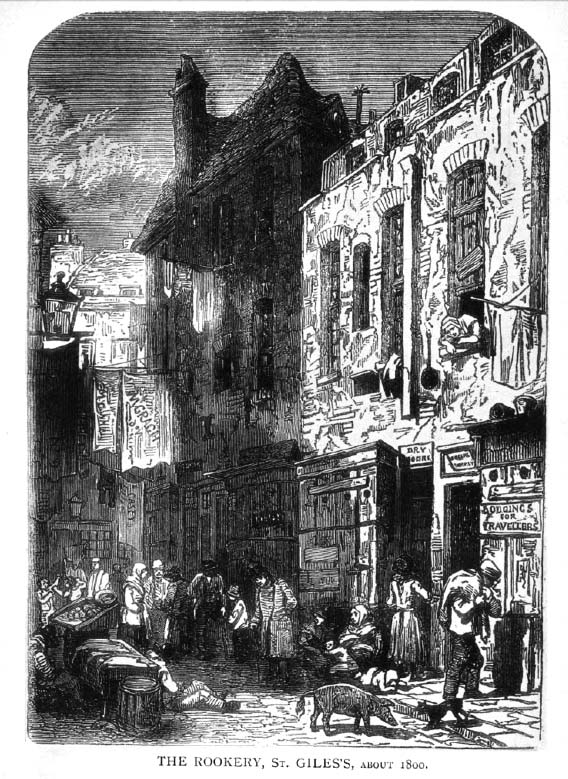

On the afternoon of October 17th 1814 one of the iron rings around the tank snapped. About an hour later the whole tank ruptured, releasing the hot fermenting ale with such force that the back wall of the brewery collapsed. The force also blasted open several more vats, adding their contents to the flood which now burst forth onto the street. More than 320,000 gallons of beer were released into the area. This was St Giles Rookery, a densely populated London slum of cheap housing and tenements inhabited by the poor, the destitute, prostitutes and criminals.

The flood reached George Street and New Street within minutes, swamping them with a tide of alcohol. The 15 foot high wave of beer and debris inundated the basements of two houses, causing them to collapse. In one of the houses, Mary Banfield and her daughter Hannah were taking tea when the flood hit; both were killed.

In the basement of the other house, an Irish wake was being held for a 2 year old boy who had died the previous day. The four mourners were all killed. The wave also took out the wall of the Tavistock Arms pub, trapping the teenage barmaid Eleanor Cooper in the rubble. In all, eight people were killed. Three brewery workers were rescued from the waist-high flood and another was pulled alive from the rubble.All this ‘free’ beer led to hundreds of people scooping up the liquid in whatever containers they could. Some resorted to just drinking it, leading to reports of the death of a ninth victim some days later from alcoholic poisoning.

‘The bursting of the brew-house walls, and the fall of heavy timber, materially contributed to aggravate the mischief, by forcing the roofs and walls of the adjoining houses.’ The Times, 19th October 1814.

Some relatives exhibited the corpses of the victims for money. In one house, the macabre exhibition resulted in the collapse of the floor under the weight of all the visitors, plunging everyone waist-high into a beer-flooded cellar.The stench of beer in the area persisted for months afterwards. The brewery was taken to court over the accident but the disaster was ruled to be an Act of God, leaving no one responsible.

The flood cost the brewery around £23000 (approx. £1.25 million today). However the company were able to reclaim the excise duty paid on the beer, which saved them from bankruptcy. They were also granted ₤7,250 (₤400,000 today) as compensation for the barrels of lost beer.

This unique disaster was responsible for the gradual phasing out of wooden fermentation casks to be replaced by lined concrete vats. The Horse Shoe Brewery was demolished in 1922; the Dominion Theatre now sits partly on its site.

Toten Hall house in Tottenham Court Road, destroyed by the beer flood.

This is from h2g2 The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: Earth Edition.

Come October of 1814, the beer had been fermenting atop the brewery for months (as was the need with porter), and the metal and wood of this huge vat was, unbeknownst to the majority of the brewery workers3, beginning to show the strain of holding back the thousands of litres. Suddenly, at about 6.00pm, one of the heavy metal hoops snapped and the contents of the porter vat exploded out – quite literally – causing a chain reaction with the surrounding vats. The resulting noise was apparently heard as far away as five miles!

A total of 1,224,000 litres of beer under pressure smashed through the twenty-five foot high brick wall of the building, and gushed out into the surrounding area – the slum of St Giles. Many people lived in crowded conditions here, and some were caught by the waves of beer completely unaware. The torrent flooded through houses, demolishing two in its wake, and the nearby Tavistock Arms pub in Great Russell Street suffered too, its 14-year-old barmaid Eleanor Cooper buried under the rubble. The Times reported on 19 October of the flood:

The bursting of the brew-house walls, and the fall of heavy timber, materially contributed to aggravate the mischief, by forcing the roofs and walls of the adjoining houses.

Fearful that all the beer should go to waste, though, hundreds of people ran outside carrying pots, pans, and kettles to scoop it up – while some simply stooped low and lapped at the liquid washing through the streets. However, the tide was too strong for many, and as injured people began arriving at the nearby Middlesex Hospital there was almost a riot as other patients demanded to know why they weren’t being supplied with beer too – they could smell it on the flood survivors, and were insistent that they were missing out on a party! Calm was quickly restored at the hospital, but out in the streets was a different matter.

Back at the brewery, one man managed to save his brother from going under the vast wave, but as the tide receded the true damage could be discovered. The beer tsunami left nine people dead4; many had drowned (like Mary Mulvey and her 3-year-old son Thomas), others were swept away in the flood and died of the injuries they sustained (two young children: Hannah Banfield, 4, and Sarah Bates, 3), and the final victim actually succumbed some days later of alcohol poisoning – such was his heroic attempt to stem the tide by drinking as much beer as he humanly could.

Because of the poverty of the area, relatives of the drowned took to exhibiting their families’ corpses in their homes and charging a fee for viewing. In one house, though, too many people crowded in and the floor gave out, plunging them all into a cellar half full of beer. This morbid exhibition moved locations, attracting more custom – and eventually the police, who closed the doors on the horrible circus. Later, the funerals of the dead were paid for by the St Giles population, coins left on their coffins. The stench of the beer apparently lasted for months, and after the initial excitement, many found both their homes and livelihoods swept away with the flood. In amongst the misery of clearing away the dead and cleaning up the streets, though, there was compassion. The Times concluded:

The emotion and humanity with which the labourers proceeded in their distressing task excited a strong interest, and deserves warm approbation.

The Meux Brewery Company was taken to court over the accident, but the judge ruled that although devastating, the flood was an ‘Act of God’ and the deaths6 were simply by ‘casualty’. In other words, no party was to blame, and the company continued working despite the incident. Up until 1961 that is, when it was sold to Friary, Holroyd and Healy’s Brewery Ltd of Guildford. The firm became Friary Meux Ltd for only three years, before being bought outright by Ind Coope (& Allsop) of Burton-on-Trent.

Apparently the only eyewitness account to the flood was from an American tourist who chose the wrong shortcut:

All at once, I found myself borne onward with great velocity by a torrent which burst upon me so suddenly as almost to deprive me of breath. A roar as of falling buildings at a distance, and suffocating fumes, were in my ears and nostrils. I was rescued with great difficulty by the people who immediately collected around me, and from whom I learned the nature of the disaster which had befallen me. An immense vat belonging to a brew house situated in Banbury street [sic – now Bainbridge Street], Saint Giles, and containing four or five thousand barrels of strong beer, had suddenly burst and swept every thing before it. Whole dwellings were literally riddled by the flood; numbers were killed; and from among the crowds which filled the narrow passages in every direction came the groans of sufferers.

There are quite a few more accounts, such as History Nuggets, Damn Interesting, the History Channel, and The Independent. But naturally, the best account os from Martyn Cornell, the Zythophile, in So what REALLY happened on October 17 1814?

Meux’s Horseshoe Brewery, around 1906.

This version of the story, a bit altered from reality, appeared in the comic book “Doctor Who #4” (December 2012), with a script by Brandon Seifert, pencils by Philip Bond, inks by Ilias Kyriazis, colors by Charlie Kirchoff, and letters by Tom B. Long:

And here’s a short video on the flood, from American Adventure Survival Science (and please note, the host is wearing a Bagby Beer Co. shirt):