![]()

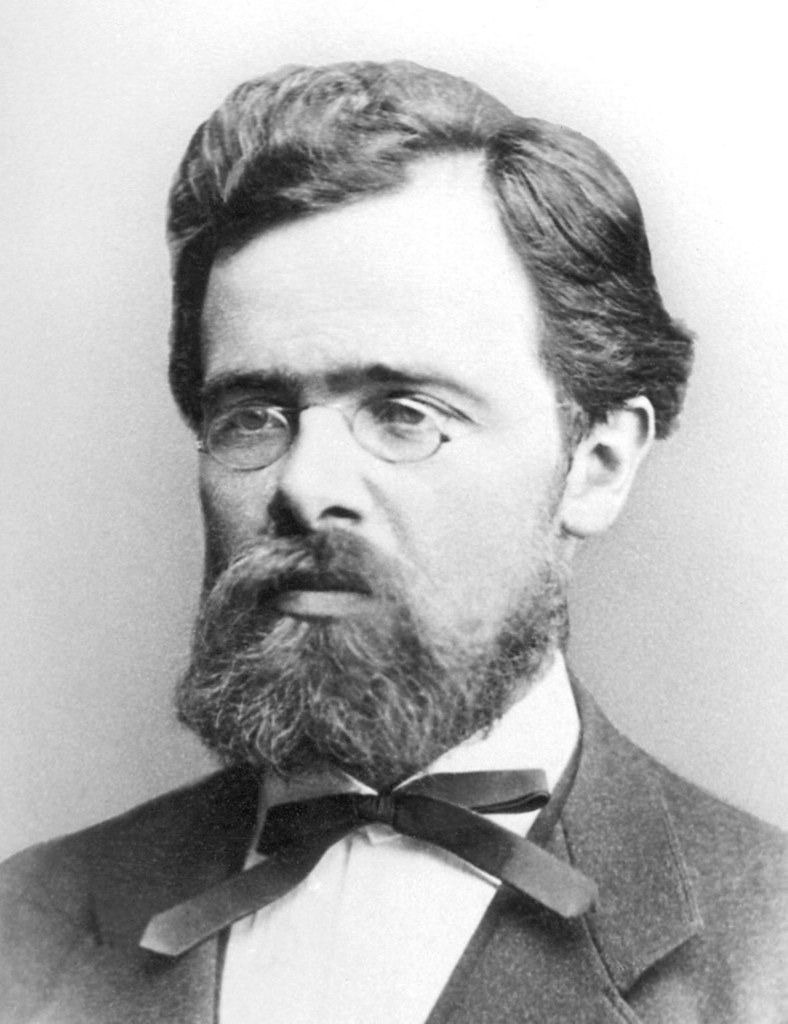

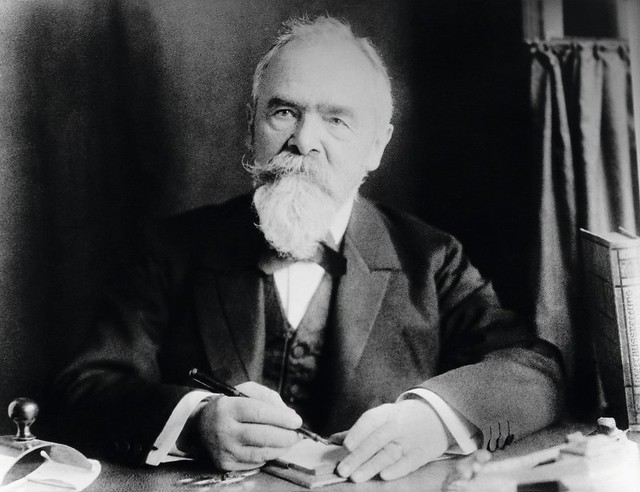

Today is the birthday of Carl Paul Gottfried Linde (June 11, 1842–November 16, 1934). He “was a German scientist, engineer, and businessman. He discovered a refrigeration cycle and invented the first industrial-scale air separation and gas liquefaction processes. These breakthroughs laid the backbone for the 1913 Nobel Prize in Physics. Linde was a member of scientific and engineering associations, including being on the board of trustees of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt and the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Linde was also the founder of what is now known as The Linde Group, the world’s largest industrial gases company, and ushered the creation of the supply chain of industrial gases as a profitable line of businesses. He was knighted in 1897 as Ritter von Linde.”

His importance to brewing, especially yo lager beers, is undeniable. His first refrigerating machines were built for breweries. This is situation prior to his inventions, from the University of Chicago:

Before the development of mechanical refrigeration technologies, brewers were reliant on ice harvested from lakes and ponds and stored in ice-houses. The invention of mechanical refrigeration machines provided commercial brewers with the technology necessary to keep beer for longer periods of time. Refrigeration technology was also used in special railroad boxcars, permitting brewers to ship their product over longer distances. One of the most successful early designs for a mechanical refrigeration system was invented by Carl von Linde (a professor at Munich Polytechnic School) and was an ammonia-based vapor-compression system.

This history of the development of Linde’s refrigeration machines is from a brochure prepared by his the company he founded, The Linde Group.

Initial contacts with breweries

After von Linde had published his ideas in 1870 and 1871 in the Polytechnic Association’s “Bavarian Industry and Trade Journal,” which he also edited, a development was set in motion that would determine the direction of the entire rest of his life. His articles on refrigeration technology had aroused the interest of brewers who had been looking for a reliable year-round method of refrigeration for the fermentation and storage of their beer. In the summer of 1871 an agreement was made between von Linde, Austrian brewer August Deiglmayr (Dreher Brewery) and Munich brewer Gabriel Sedlmayr to build a test machine according to Linde’s design at the Spaten Brewery. With their help, Linde’s ideas would be put into practice, so that a refrigeration unit could then be installed at the Dreher Brewery, the largest brewery in Austria, in the hot, humid city of Trieste (now part of Italy).

Building the first Linde ice machine

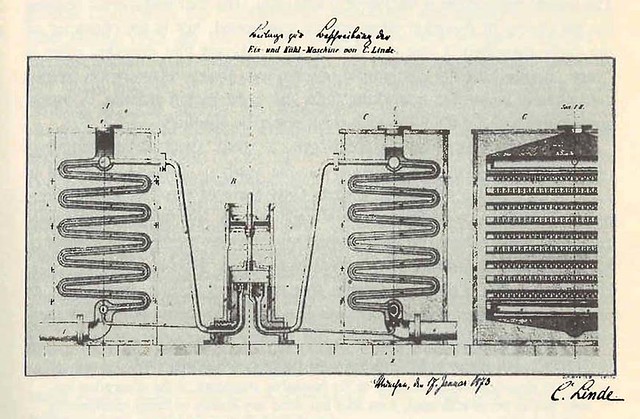

The construction plans were finally completed in January 1873 and the patent applied for. The Bavarian patent required, however, that the machine be in operation within one year. Therefore von Linde and Sedlmayr placed an order with Maschinenfabrik Augsburg that same month to build it. And with some effort they succeeded in starting operation by the important patent deadline in January 1874. Of course, the first machine did have its difficulties.

The main problem was that von Linde’s mercury seal did not work properly so that the methyl ether used as the refrigerant leaked out of the compressor. In Linde’s words, “This design was not a suitable solution for the requirements of practical use. So it seemed imperative to build a second machine.”

In order to finance it, von Linde assigned part of the patent rights to Sedlmayr, to locomotive builder Georg Krauss and to the director of Maschinenfabrik Augsburg, Heinrich von Buz. In return, they provided the funds needed for the development, building and testing of a new refrigeration machine.

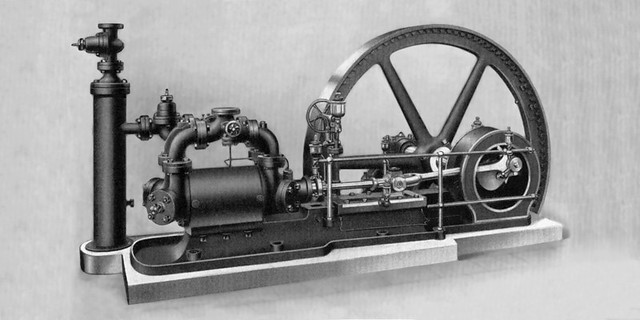

With his student and assistant Friedrich Schipper, von Linde designed a new compressor, which had a significantly simpler and more effective seal. The sealing material used in the newly designed gland construction was glycerin and the more efficient ammonia was used as the refrigerant. The new machine weighed and cost only half as much as its predecessor.

In the spring of 1875 Linde ordered the new compressor from Maschinenfabrik Augsburg and submitted it for a Bavarian patent, which was awarded on March 25, 1876 for ten years. He received the German Reichspatent in August 1877.

“The very first trials with this second compressor yielded fully satisfactory results,” said von Linde, not without pride. The machine was sold to the Dreher Brewery in September 1876, erected under Schipper’s supervision and started up in spring 1877. It ran until 1908, providing refrigeration and dehumidification

Technical breakthrough

But despite this success, Linde created a third design immediately after the second machine was installed at Dreher, turning his attention to gas pumps, which were already widely used. This third, horizontal design proved to be the best cold vapor machine on the market in terms of its price/performance ratio and became the standard type of Linde compressor for decades to come. During the more than six-year development and experimentation phase, a reliable solution also had to be found for distributing the generated cold. After long trials, in executing an order for the Heineken Brewery in Rotterdam, von Linde developed a method of circulating cold saltwater brine in a pipe cooling system (natural convection cooling), which was installed on the ceiling of the refrigeration rooms.

In 1840, many continental European breweries switched to bottom fermented lager production (in contrast to the “English” top-fermented brown beers or ales) because the beer remained fresh longer and customers preferred the taste. The ice machine described by von Linde seemed ideal for achieving the required lower temperatures and to ensure precise cooling control. So it is no wonder that some major brewers showed great interest in this invention.

Gabriel Sedlmayr of the Munich Spaten Brewerey was willing to let von Linde experiment with an early refrigeration machine in his brewery in the early 1870s. The first unit functioned passably well, but was too large and had numerous flaws. The drawings submitted for the patent showed that Sedlmayr himself had a hand in the second version, which was significantly smaller in size and worked well. This unit was sold to the Trieste Dreher Brewery for air cooling.

With Sedlmayr as an intermediary, the Rotterdam Heineken Brewery under its director Feldmann ordered an ice machine in 1877 for ice production. In his collaboration with the Heineken Brewery, Linde developed “natural convection cooling” with a system of cooling pipes under the ceiling of the cellar. Feldmann in turn put von Linde in contact with J. C. Jacobsen, head of the Carlsberg Brewery in Copenhagen, who ordered a large refrigeration unit in 1878.

Karl Lang, technical adviser and supervisory board member of several Rhineland breweries, also played a significant role during the founding period of the “Gesellschaft für Linde’s Eismaschinen.” He introduced Linde to brewery director Gustav Jung, who not only ordered a refrigeration unit but also became, with Lang and banker Moritz von Hirsch, a shareholder and Supervisory Board member of the Linde Company.

The connection between the Linde Company and brewery directors was maintained to some extent over several generations. After the death of Karl Lang in 1894 his position as chairman of the Supervisory Board was taken over by Gustav Jung, followed by his son Adolf Jung in 1886. Carl Sedlmayr took over for his father Gabriel on the Supervisory Board and in 1915, the third generation of this family followed with Anton Sedlmayr. The Jung and Sedlmayr families held their Supervisory Board seats until after the Second World War.

Here’s Linde’s entry from the Oxford Companion to Beer, written by Horst Dornbush.

Linde, Carl von

was a 19th-century German engineer and one of the world’s major inventors of refrigeration technology. See refrigeration. Starting in the middle of the 18th century, many people before Linde had tinkered with artificial refrigeration contraptions, but Linde was the first to develop a practical refrigeration system that was specifically designed for keeping fermenting and maturing beer cool—in Linde’s case, Bavarian lagers—during the hot summer months. Linde was born in the village of Berndorf, in Franconia, in 1842, at a time when warm-weather brewing was strictly forbidden in his native Bavaria; no one was allowed to brew beer between Saint George’s Day (April 23) and Michael’s Day (September 29). This was to avoid warm fermentations, which provided ideal habitats for noxious airborne bacteria to proliferate and caused yeasts to produce undesirable fermentation flavors. Both made summer beers often unpalatable. Summer brewing prohibition had been in force since 1553 and was only lifted in 1850, by which time Bavarian brewers had learned to pack their fermentation cellars with ice they had laboriously harvested in the winter from frozen ponds and lakes. There had to be a better way to keep beer cold…and that was just the challenge for a budding mechanical engineering professor like Linde, who had joined Munich’s Technical University in 1868. See weihenstephan. The basic principle of refrigeration had been understood for centuries. Because cold is merely the absence of heat, to make things cold, one must withdraw heat. Compressing a medium generates heat; subsequently decompressing or evaporating it quickly absorbs heat from its environment. Devices based on this principle are now generally known as vapor-compression refrigeration systems; apply this to a fermenting or lagering vessel, and it becomes a beer-cooling system. For Linde, the next question was the choice of refrigerant. Initially he experimented with dimethyl ether but eventually settled on ammonia because of its rapid expansion (and thus cooling) properties. He called his invention an “ammonia cold machine.” Linde had received much of the funding for this development from the Spaten Brewery in Munich, which was also the first customer to install the new device—then still driven by dimethyl ether—in 1873. By 1879, Linde had quit his professorship and formed his own “Ice Machine Company,” which is still in operation today as Linde AG, headquartered in Wiesbaden, Germany. By 1890, Linde had sold 747 refrigeration units machines to various breweries and cold storage facilities. He continued to innovate and invented new devices most of his life, including equipment for liquefying air, and for the production of pure oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen. In 1897 he was knighted, and from then on could append the honorific “von” to his surname. He died a prosperous industrialist in Munich in 1934, at the age of 92, and today Linde AG is a leading gases and engineering company with almost 48,000 employees working in more than 100 countries worldwide. For all his many accomplishments, Linde’s pioneering work in artificial beer cooling technology is perhaps his most enduring legacy.