![]()

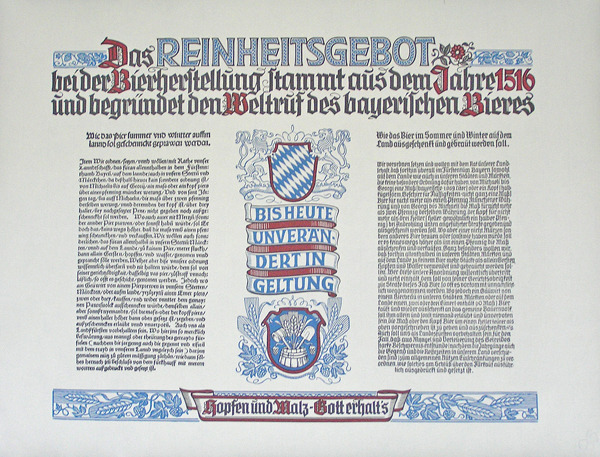

It’s hard to believe it’s been 500 years since Bavaria signed what’s considered the first food purity law, the Reinheitsgebot, also known as the Bavarian Beer Purity Law, and later the German Beer Purity Law. That’s because in 1516, when the law was decreed, Germany did not yet exist, and wouldn’t for nearly 300 years, with the formation of the German Confederation in 1815, longer if you go by the German Empire, founded in 1871. Modern Germany consists of sixteen federal states, called Bundesländers, of which Bavaria is one.

And it was in Bavarian town of Ingolstadt on April 23, 1516, that William IV, Duke of Bavaria wrote and signed the law, along with his younger brother Louis X, Duke of Bavaria. That 1516 law was itself a variation of earlier laws, at least as early as 1447 and another in independent Munich in 1487. When Bavaria reunited, the new Reinheitsgebot applied to the entirety of the Bavarian duchy. It didn’t apply to all of Germany until 1906, and it wasn’t referred to as the Reinheitsgebot until 1918, when it was coined by a member of the Bavarian parliament. But while today most people think of it as all about food purity, that was in reality only a small part of it, and probably not even the most important.

Here’s a translation of the Reinheitsgebot, from a 1993 issue of Zymurgy:

We hereby proclaim and decree, by Authority of our Province, that henceforth in the Duchy of Bavaria, in the country as well as in the cities and marketplaces, the following rules apply to the sale of beer:

From Michaelmas to Georgi [St. George’s Day], the price for one Mass [Bavarian Liter 1,069] or one Kopf [bowl-shaped container for fluids, not quite one Mass], is not to exceed one Pfennig Munich value, and

From Georgi to Michaelmas, the Mass shall not be sold for more than two Pfennig of the same value, the Kopf not more than three Heller [Heller usually one-half Pfennig].

If this not be adhered to, the punishment stated below shall be administered.

Should any person brew, or otherwise have, other beer than March beer, it is not to be sold any higher than one Pfennig per Mass.

Furthermore, we wish to emphasize that in future in all cities, markets and in the country, the only ingredients used for the brewing of beer must be Barley, Hops and Water. Whosoever knowingly disregards or transgresses upon this ordinance, shall be punished by the Court authorities’ confiscating such barrels of beer, without fail.

Should, however, an innkeeper in the country, city or markets buy two or three pails of beer (containing 60 Mass) and sell it again to the common peasantry, he alone shall be permitted to charge one Heller more for the Mass or the Kopf, than mentioned above. Furthermore, should there arise a scarcity and subsequent price increase of the barley (also considering that the times of harvest differ, due to location), WE, the Bavarian Duchy, shall have the right to order curtailments for the good of all concerned.

Notice that the first two decrees have to do with pricing and when beer can be sold. It isn’t until paragraph six, the second last one, that the issue of what ingredients will be allowed comes up. If it had been the most important part, is seems more likely they would have led with it. Even then, it wasn’t about purity, but again commerce. Barley was designated as the only grain so that others, notably wheat and rye, were set aside to be used for baking bread.

Also, a lot of hay has been made about it not mentioning yeast, with the idea that it was because yeast wasn’t discovered until Louis Pasteur in the 19th century. But early brewers did know something about yeast, even if they didn’t have the full scientific understanding that came later. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have been able to make consistent batches of beer. At the end of your brew, you’ll find a layer of billowing foam and other indeterminate matter at the bottom of the fermenter, which the Germans called “Zeug,” which means “stuff.” And early German brewers had a person, called a “hefener,” whose job it was to scoop out the Zeug, which was in effect the leftover yeast, and pitch it in the next batch of beer. So it’s hard to say they didn’t have some understanding of yeast.

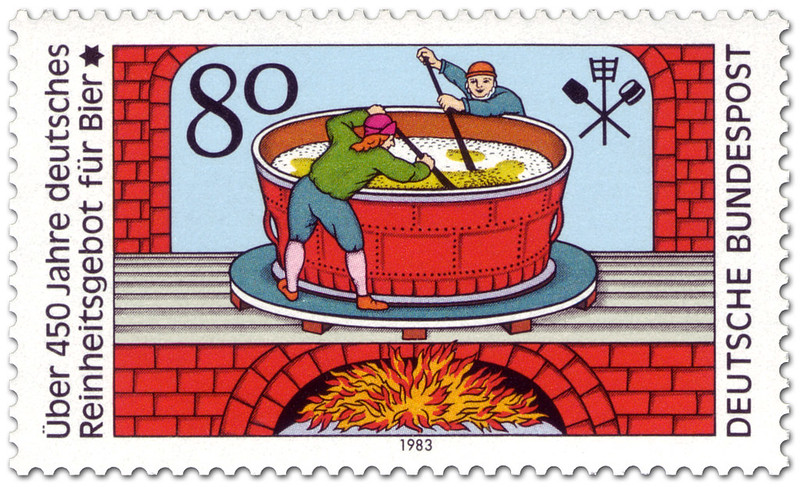

A German postage stamp celebrating the 450th anniversary of the Reinheitsgebot in 1983.

The Germans, of course, have set up a website for the 500th anniversary, and so does the Bayerischer Brauerbund, which is a a Bavarian brewers trade group along with the German Brewers Group. They also created a 50-second film marking the anniversary.

And the media is covering the Reinheitsgebot’s Quincentenary. A few examples include the BBC, Food and Wine, NPR, Spiegel, and Wired. But by far the most thorough examination of the Reinheitsgebot was by Jeff Alworth in All About Beer magazine, Attempting to Understand the Reinheitsgebot.

It’s great that it’s been 500 years, and that German brewers are justly proud of the Reinheitsgebot. It’s clearly helped create the unique German beer scene and their many native styles. But it’s also been used as a shameless marketing tool, been used as an exclusionary tactic, and has even had little-known exceptions to its rules for years, ones that most people are not even aware of, not to mention the use of other items in the brewing process that are also not mentioned by the law, but which because they’re not strictly “ingredients” more modern brewers have interpreted as not being prohibited.

Many people have voiced criticisms against it over the years. One that’s particularly thorough is The German Reinheitsgebot — Why it’s a Load of Old Bollocks. The German magazine Spiegel’s recent coverage is entitled Attacking Beer Purity: The Twilight of Germany’s Reinheitsgebot.

Back in 2001, Fred Eckhardt wrote an entertaining tale for All About Beer entitled The Spy who Saved the Reinheitsgebot, about how a brewer was able to prove Beck’s was using adjuncts and was not in adherence with the German law.

In another recent article in First We Feast, Sam Calagione, of the Dogfish Head Craft Brewery, is quoted with an opinion I suspect many American brewers hold. “I hate the concept of the Reinheitsgebot, but I am essentially happy it exists.”

Deutsche Post’s 2016 commemorative stamp.