![]()

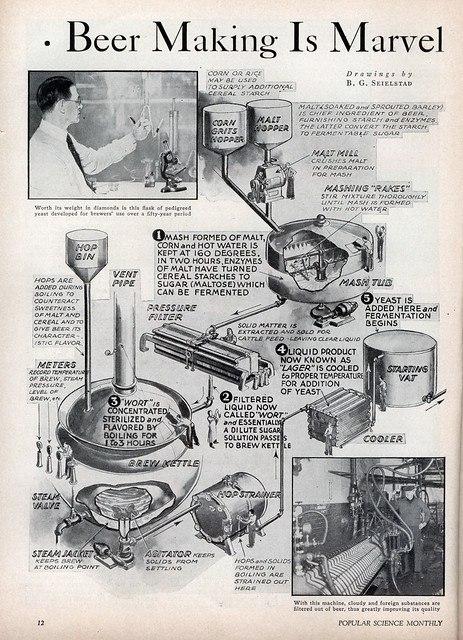

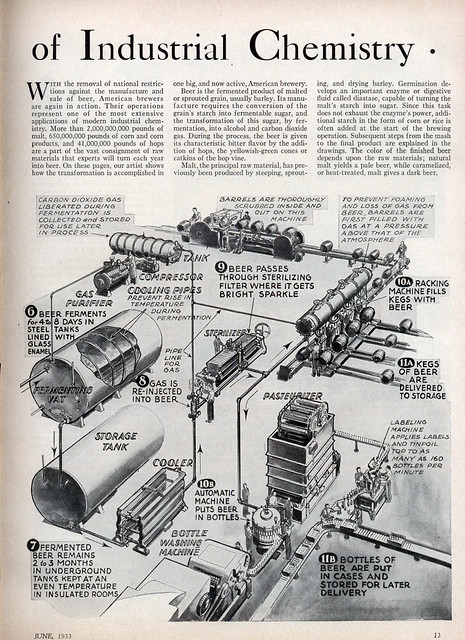

In June of 1933, just as Prohibition was in its death throes, that month’s issue of Popular Science magazine ran a two-page spread entitled Beer Making Is Marvel Of Industrial Chemistry, illustrated by Benjamin Goodwin Seielstad. It’s great fun to see it all laid out the way it’s done here. It seems like they were laying the groundwork for the return of brewing in America.

There’s not a great deal of text accompanying the chart, but here it is in its entirety, from page two of the beer making chart:

With the removal of national restrictions against the manufacture and sale of beer, American brewers are again in action. Their operations represent one of the most extensive applications of modern industrial chemistry. More than 2,000,000,000 pounds of malt, 650,000,000 pounds of corn and corn products, and 41,000,000 pounds of hops are a part of the vast consignment of raw materials that experts will turn each year into beer. On these pages, our artist shows how the transformation is accomplished in one big, and now active, American brewery.

Beer is the fermented product of malted or sprouted grain, usually barley. Its manufacture requires the conversion of the grain’s starch into fermentable sugar, and the transformation of this sugar, by fermentation, into alcohol and carbon dioxide gas. During the process, the beer is given its characteristic bitter flavor by the addition of hops, the yellowish-green cones or catkins of the hop vine.

Malt, the principal raw material, has previously been produced by steeping, sprouting, and drying barley. Germination develops an important enzyme or digestive fluid called diastase, capable of turning the malt’s starch into sugar. Since this task does not exhaust the enzyme’s power, additional starch in the form of corn or rice is often added at the start of the brewing operation. Subsequent steps from the mash to the final product are explained in the drawings. The color of the finished beer depends upon the raw materials; natural malt yields a pale beer, while caramelized, or heat-treated, malt gives a dark beer.

“2B lbs of malt, 650M lbs of corn and 41M lbs of hops”. Those numbers seem crazy high but when you look at the industry as a whole, I can see why it quickly adds up. Having grown my own hops, I was ecstatic to have harvested ~37 ounces from one plant. It was a lot of work and I can only imagine what 41M lbs of hops must look like.

@Peter – Those raw material quantities were estimates, since full Repeal had not yet happened- and optimistic ones at that. For 1934, the actual totals of “Consumption of Agricultural Products” (from The Brewers Digest) was:

Malt – 1.4b lbs.

Corn – 256.8m lbs.

Rice – 102.9m lbs.

Sugar/syrups 142.4m lbs

Hops – 26.2 m lbs.

With 37. 8 million barrels of beer produced. It took sometime (1940) to reach pre-Prohibition totals and even longer to get back to pre-Pro per capita rates (1970’s, by one set of numbers).

Very cool. I wonder what brewery the artist visited for research, and whether they actually mashed at 160 F. Seems a bit high.

If you struggled in chemistry class, maybe it wasn’t you, it was the course materials. I never saw anything like this in my textbooks.

I love the Rube Goldberg-ish drawings and the concise text. But what’s interesting is that the description of keg filling includes a mention of what we now call “counter-pressure”, but the bottle filling has no such similar mention.

That they used recycled CO2 from the fermentation process for recarbonation surprised me – is that still “normal” practice for the megabrewers?

Great post, Jay!