![]()

The UK tabloid newspaper, The Daily Mirror, reported today that a study at the University of Barcelona revealed that “[d]rinking up to a pint of beer a day is good for your health — and can even help you lose weight.” They also “found those who have a Mediterranean-style diet and drink moderately are healthier than those who don’t” and that “beer could cut the risk of high blood pressure.”

Beer In Ads #203: Epidor Moritz

Monday’s ad is for a Spanish brewery, Moritz in Barcelona, which was founded in 1856 and closed in 1978. Remaining family members started up the brand again a few years ago, contracting the brewing. This ad is for Epidor, a strong lager they debuted July 23, 1923. Given the strange face of the man in the ad, I’m not exactly sure who their target audience was or why they thought that would help sell beer. Does it make you want to drink their beer?

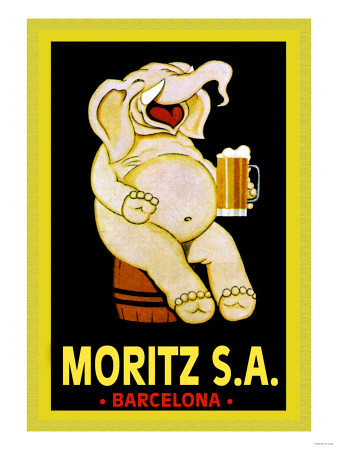

Beer In Ads #199: The Moritz Elephant

Tuesday’s ad is for a Spanish beer, Moritz. The Barcelona brewery was founded in 1856 and closed in 1978, but remaining family members started up the brand again a few years ago, contracting the brewing. This ad is from the first half of the last century, and I particularly love the laughing elephant with his mug of beer.

Beer In Ads #31: Estrella Damm’s Waves

Wednesday’s ad is a contemporary one for Spain’s Estrella Damm. The illustration was apparently done for an Estrella Damm calendar. This work was done by Alex Trochut, a Spanish artist living in Barcelona. There’s a nice biography and short interview with him at It’s Nice That. I love art with a lot of detail, and this one has it in spades. Look closely at the waves and that alone should keep you occupied for some time. To see it larger, and see even more detail, click through the image and then select “all sizes.”

Beer In Ads #2: The Spanish Senorita

Today’s beer ad is a beautiful illustration by Achille Mauzan, an Italian artist who created many posters and other illustrations during the Art Deco period from the 1920s-40s and beyond. He was born Luciano Achille Mauzan in the French Riviera but spent most of his life in Italy and Argentina. This ad was created for an unknown Spanish beer, depicting a senorita, “adorned in customary garb, having this brand fixed atop a staff-like scepter.”

Session #32: Drink East, Young Man

![]()

Session #32 heads east this month, courtesy of Girl Likes Beer, whose personal goal to sample a beer from every country with their own brewery. She’s had quite a few west of her native Poland, but the east is still largely unexplored. So she’s invited us to go east with her. She explains:

I would like you to pick your favorite beer made east from your hometown but east enough that it is already in a different country. It can be from the closest country or from the furthest. Explain why do you like this beer. What is the coolest stereotype associated with the country the beer comes from (of course, according to you)? And one more thing. If you do a video or picture of the beer (not obligatory of course) try to include the flag of the country.

Where I live in Marin County, California is roughly along the 38th Parallel. Following the line of 38 degrees of latitude east, the next countries one encounters, not including a few Atlantic islands, are Portugal and Spain. As I don’t necessarily have a favorite from those nations readily at hand, I’ll go instead for most recently tried. The most recent Spanish beer I’ve tried, is INEDIT, created by Grupo Damm in Barcelona, Spain. Below is my review of it that was published on one of my other blogs, Bottoms Up.

Apparently when Ferran Adrià does something new, the food world pays attention. He’s considered one of the world’s great chefs and cooks at el Bulli, his restaurant in Girona, which is in the Catalonia region of Spain. In 2004, he was listed in Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. So he’s no doubt a superstar in the restaurant biz.

![]()

Adrià recently lent his expertise to beer-making and worked with Spanish brewery Grupo Damm in Barcelona to help create INEDIT, a beer specifically designed as a food beer. Damm is best known for their flagship Estrella Damm, a decent, if unexceptional, example of a European lager, somewhat similar to Heineken or Stella Artois. So if you were going to pair up with a brewery to make a food beer, whatever that even means, there might be better choices, breweries that already understand the balancing of flavors between beer and food, for example.

Cooking, it should be pointed out, does not automatically make one an expert on beer any more than it makes a brewer an expert chef. The press release claims that designing the beer took 1 1/2 years and “400 trial iterations between the master brewers of Estrella Damm,” Adrià, his retaurant partner Juli Soler, and two of the sommeliers from el Bulli. If you know anything about brewing and how long the average batch takes, if might cause you to wonder how it was possible to brew 400 batches in such a short period of time.

At the Damm website, the reason given for why they wanted to make this beer is explained.

Inedit is the first beer specifically created to accompany food. It is born from the conviction that a beer that could be paired with the utmost respect to the best cuisine was necessary. That is its aim and its virtue, and that is what makes Inedit different, special and unique.

A fine sentiment, except that most craft beer along with many of the fine beers brewed in Belgium, Germany, England and others have already been brewed with food in mind. It’s just part and parcel of any good artisanal beer that its very design, its particular ingredients, and the process by which it was brewed all assures it will be an excellent compliment or contrast with just the right food. Many chefs who have been working with beer for years, such as our own Bruce Paton, the beer chef, already know this to be true and have made a living out of discovering those perfect pairings.

But the press releases really trips over itself:

Developed for gastronomy, INEDIT is an alternative to wine for pairing with all dishes — from informal to more exquisite, sophisticated types of food. INEDIT is a unique coupage of barley malt and wheat with spices which provide an intense and complex aroma. It aims to complement food once thought to be a challenge in terms of culinary pairings, including salads, vinegar-based sauces, bitter notes such as asparagus and artichokes, fatty and oily fish, and citrus.

With its delicate carbonation, INEDIT adapts to acidic, sweet and sour flavors. Its appearance is slightly cloudy, and INEDIT has a yeasty sensation with sweet spices, causing a creamy and fresh texture, delicate carbonic long aftertaste, and pleasant memory. The rich and highly adaptable bouquet offers a unique personality with a smooth, yet complex taste.

Unlike most beers, INEDIT is bottled in a 750 ml black wine bottle and is intended for sharing. INEDIT is to be served in a white wine glass, filled halfway and chilled in a cooler.

All well and good, except that how is it possible every beer aficionado knows something, something they take for granted even, that Adrià and his crew do not; which is that beer is, and has always been, a wonderful match with challenging foods.

The very idea of there being an all-purpose beer “for pairing with all dishes” suggests they don’t really understand beer’s complexities at all. No chef worth his salt would ever suggest there’s one wine that might go with any dish, but beer has for so long suffered in the shadows, and many chefs, sadly, think that beer is just one thing: the mass-produced adjunct swill that people guzzle at sporting events.

That they’ve missed the boat is again made obvious by the statement that “[u]nlike most beers, INEDIT is bottled in a 750 ml black wine bottle and is intended for sharing.” There are many, many beers that are bottled in a 750 ml size, not to mention the 22 oz. bomber, which has been around for decades. Both are, and always have been, for sharing.

Then there’s the serving suggestions, that it “be served in a white wine glass, filled halfway and chilled in a cooler.” I’m okay with the white wine glass — sort of — but Belgians and others have specifying particular glassware for their beer for a century or longer. I feel confident that there’s a beer glass that could work, too. But chilling it in a cooler? I don’t even understand that. Is that done with white wine? Is the wine put in the glass and then both are placed in a cooler to chill? Or do they mean that the glass should be chilled in a cooler first, a milder version of a frosted glass? Either way it’s a bad idea, something you should never do to your beer. It probably wouldn’t hurt it the way a frosted glass has the potential to harm beer, but it’s a road we shouldn’t even start traveling down.

But let’s forget all the hype and just talk about the beer itself. After all, that’s really what’s most important. Not surprisingly, Inedit does not live up to the hype. How could it? It’s not that it’s bad, it’s really not, but it’s hardly exceptional in a field in which there are literally countless examples of better beers to pair with food, perhaps hundreds of them being brewed right now just in the Bay Area. Try Arne Johnson’s Point Reyes Porter (from Marin Brewing) with a fine Mexican mole, for example. Absolute heaven. Or Vinnie Cilurzo’s Salvation (from Russian River Brewing) with the Chili Chocolate Mousse featured by Bruce Paton yesterday in his Food & Beer piece. Another slice of heaven. But let’s get back to Inedit.

Inedit’s nose is surprisingly subtle with few spices coming through. As it warms, some of them do start to appear, though still they remain underneath. The sweetness is what comes through on the nose. It’s slightly cloudy like a witbier, though apparently it’s a blend of a lager (most likely something similar to Estrella Damm) and, they claim, a German-style weissbier. There’s no hint of cloves or banana in the nose, suggesting instead that a weissbier yeast has not been used. It has been brewed with orange peel, coriander and licorice. Orange peel and coriander are common ingredients in a Belgian-style wit or white beer, though not a Bavarian-style weissbier. It is unfiltered and is 4.5% a.b.v.

The mouthfeel is a little thin though the flavors do exhibit some creaminess. Again it’s sweet flavors that dominate the palate, with what spices that do come through being very subtle and remaining in the background throughout. The lager blend seems to contribute a nice clean character, and the finish is quick and similarly clean, dropping off almost immediately. It’s not a bad beer, though there’s no real synergy to the blend, as if it can’t make up its mind what it wants to be. It could work fine with a light salad or some other light fare, but I don’t think it would stand up to heavier flavors very well. At around $9.99, it’s not a bad deal, just don’t expect to be wowed.

I noticed a curious thing though about how this beer’s been received in the two weeks since it was first opened to great fanfare at chef Dan Barber’s Blue Hill at Stone Barns. Barber’s another big time chef, and this year he was picked by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people, and it was none other than Ferran Adrià who wrote about Barber for Time. People who’ve reviewed this beer seem to be split down the middle along some telling lines. Beer reviewers seem to consider it, as I do, as average at best. But many food writers, presumably because anything Adrià does is newsworthy, wrote uncritically about it, accepting what was in the press release and passing it along verbatim without question. I’ll let you decide what conclusions to draw from that.

In the New York Times, food writer Florence Fabricant gushes that it “behaves like a wine,” which personally I take as an insult, though I know she doesn’t mean it that way. I suspect Fabricant and other food and wine writers will continue to not quite know what to make of this beer, simply because they don’t seem to really understand it. Fabricant continues by saying later in the short review that Inedit “undergoes a second fermentation in the bottle, like Champagne.” Except that its secondary fermentation, in the beer world, is called bottle conditioning, and is a common practice that’s at least as old as the similar method in champagne-making. There was no need to resort to wine in trying to describe what was going on in the beer.

When she interviewed Adrià last week about the beer she got this gem. “The idea was to make a beer to drink with food, from a wineglass.” The problem, as I see it, with statements like that and Fabricant’s suggestion that the beer is “behaving” like a wine is that, simply put, it isn’t, it can’t, and we shouldn’t even want it to: it’s beer. The only thing about it that makes it appear in any way wine-like is their lack of experience with beer and their apparent refusal to learn anything about it, preferring to fall back on laughingly uneducated wine comparisons. Beer is already the equal of wine in terms of complexity and sophistication, and has been for some time. Sure, there are simple beers, the most popular ones made by the big breweries, for example. But there are also box wines, table wines and Blue Nun, too. That chefs and food writers have no trouble distinguishing between fine wine and the more pedestrian varieties should prepare them to view beer in the same way, yet so few do. Don’t get me wrong, I love wine, too. But it’s just made from one thing: grapes. Beer is made from four primary ingredients (barley, hops, water and yeast). Add to that other grains (like wheat or rye) and other fruit, herbs and spices, then take it and age in a barrel. There are virtually endless combinations of these ingredients and processes that all but guarantee that the complexity that can be realized by a great beer far exceeds most, if not all, wine. These great, complex, sophisticated beers are fantastic with food, and have been for a long time. Pick up Garret Oliver’s “The Brewmaster’s Table,” Stephen Beaumont’s “beer bistro cookbook” or Lucy Saunders’ “Beer & Food, Pairing & Cooking with Craft Beer” at your local bookstore. These authors, and many others, have been writing about the pleasures of beer and food for years and years. It’s frustrating that beer has to continue to claw and fight for the respect it deserves.

Things are starting to change — slowly — and some chefs are beginning to discover that beer often pairs better with many different dishes; heavy meat dishes, cheese, and other spicy foods, to name a few. A majority of culinary schools do teach their students about wine but still ignore beer entirely. To me, that says a lot about the root of the problem. Despite decades of effort by hundreds and hundreds of small breweries to elevate the quality and status of craft beer, many still refuse to afford it the respect it’s due. That’s a shame really. They’re missing out on a lot of pleasure.

Inedit, unfortunately, will not prove to be the answer. The name, Inedit, means “novel, new or original” in French. Too bad it’s not really any of those things.

Beer in Art #11: Juan Gris’ Glass Of Beer and Playing Cards

Today’s work of art is by a Spanish painter, who painted as Juan Gris, though he real name was more of a mouthful: José Victoriano González-Pérez. Gris was a contemporary of Pablo Picasso and was also one of artists to found Cubism, though people like Picasso and Georges Braque are more well-known. Though born in Madrid, Gris spent worked most of his life in France, and was a friend of Henri Matisse, Braque and others. Most Cubists painted using a monochromatic palette, but Gris — possibly because of his friendship with Matisse — went in a slightly different direction, preferring bold, varied colors. His style of Cubism became known as synthetic cubism. His use of color is evident in today’s painting, Glass of Beer and Playing Cards, painted in 1913. The painting is in Ohio, at the Columbus Museum of Art.

Christine Poggi had this to say about the painting in her book, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage:

Gris organized Glass of Beer and Playing Cards according to a dominating pattern of vertical strips. … A coherently silhouetted beer mug might be established by shifting the vertical band that constitutes the right side of the mug upward so that the white outline becomes contiguous with the outline of the fully modeled form of the mug to its left. But this realignment would in turn disalign the continuity between the blue curvature on the orange wallpaper and the edge of the sand to the right, both forms constituting a view from above of the beer’s foam. Changes or transformations in the appearance of an object seem to occur in a number of directions: they follow the alternating rhythm of vertical bands but also the contrapuntal system of horizontal bands. Occasionally there is also a sense of transformations occurring in depth, as if Gris had peeled away the surface of certain vertical bands to reveal an alternate mode of representation or point of view beneath.

There is a little more information about Juan Gris at Wikipedia and more biographical stuff at the Art Archive. You can see over 100 of his works at the Athenaeum and also there are many links at ArtCyclopedia.