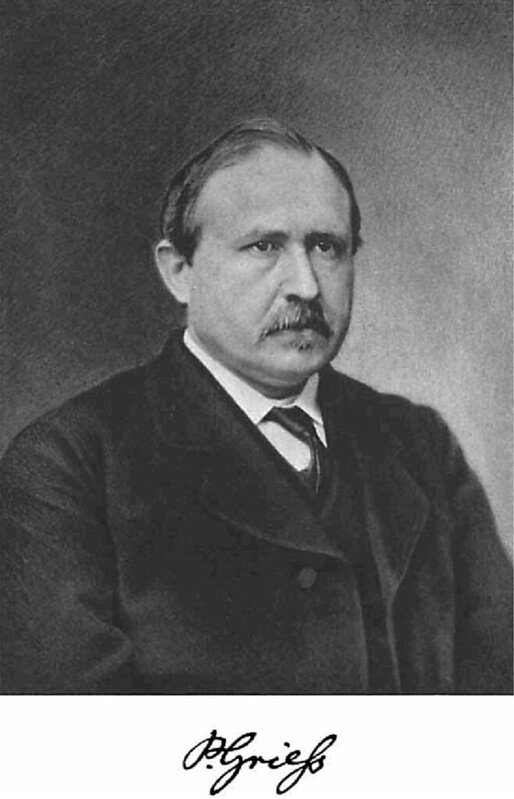

Today is the birthday of Johann Peter Griess (September 6, 1829-August 30, 1888). He was born in Kirchhosbach (now part of Waldkappel), Germany. He was “an early pioneer of organic chemistry.” While known for his work on synthetic dyes, and he was the first to develop “the diazotization of aryl amines (the key reaction in the synthesis of the azo dyes), and a major figure in the formation of the modern dye industry.” He also “worked for more than a quarter of a century at the brewery of Samuel Allsopp and Sons in Burton upon Trent, which, owing to the presence of several notable figures and an increase in the scientific approach to brewing, became a significant centre of scientific enquiry in the 1870s and 1880s.”

This is his biography from his Wikipedia page:

After he finished at an agricultural private school, he joined the Hessian cavalry, but left the military shortly after. He started his studies at the University of Jena in 1850, but changed to the University of Marburg in 1851. During his student life he was several times sentenced to the Karzer (campus jail) and was also banned from the city for one year, during which time he listened to lectures of Justus Liebig at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich. After most of the family possession had been spent, he had to start working at the chemical factory of Oehler in Offenbach am Main in 1856. This was only possible after the recommendation of Hermann Kolbe, who was head of the chemistry department in Marburg. The devastating fire of 1857 ended the production of chemicals at the factory and a changed Peter Griess rejoined Hermann Kolbe at the University of Marburg. His new enthusiasm for chemistry yielded the discovery of diazonium salts in 1858. The discovery of a new class of chemicals convinced August Wilhelm von Hofmann to invite Griess to join him at his new position at the Royal College of Chemistry. During his time at the Royal College, he studied the reactions of nitrogen-rich organic molecules. It took him quite long to become accustomed to his new home in England, but the fact that he married in 1869 and founded a family made it clear that he did not intend to return to Germany, even though he was offered a position at the BASF. He left and started a position at the Samuel Allsopp & Sons brewery in 1862 where he worked until his retirement. His wife died after a long, severe illness in 1886; he survived her for two years and died on August 30, 1888. He is buried in Burton upon Trent.

In 1858 he described the Griess diazotization reaction which would form the basis for the Griess test for detection of Nitrite. Most of his work related to brewing remained confidential, but his additional work on organic chemistry was published by him in several articles.

And this short piece is from the journal “Brewery History,” from 2005. The article was called “The Brewing Connection in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Part II,” and was written by Ray Anderson:

Another man whose activities extended far beyond his brewery work was Griess, (Johann) Peter (1829-1888), chemist to Samuel Allsopp & Sons for 26 years from 1862 until his death. Griess’s inclusion in the dictionary rests on his discovery and subsequent work on ‘a new and versatile chemical reaction which could provide a route to a wide range of new compounds’. These diazo compounds, so called because they contained two atoms of nitrogen per molecule, were to be widely utilised in the production of azo dyes, and the dictionary hails Griess’s synthesis of them as ‘perhaps the greatest single discovery in the history of the dyestuffs industry’. Historians of chemistry place Griess in the front rank of Victorian chemists.

And this is an Abstract from an article, entitled “Johann Peter Griess FRS (1829–88): Victorian brewer and synthetic dye chemist” is from “Notes and Records, The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science,” by Edwin and Andrew Yates:

The German organic chemist Johann Peter Griess (1829–88), who first developed the diazotization of aryl amines (the key reaction in the synthesis of the azo dyes), and a major figure in the formation of the modern dye industry, worked for more than a quarter of a century at the brewery of Samuel Allsopp and Sons in Burton upon Trent, which, owing to the presence of several notable figures and an increase in the scientific approach to brewing, became a significant centre of scientific enquiry in the 1870s and 1880s. Unlike the other Burton brewing chemists, Griess paralleled his work at the brewery with significant contributions to the chemistry of synthetic dyes, managing to keep the two activities separate—to the extent that some of his inventions in dye chemistry were filed as patents on behalf of the German dye company BASF, without the involvement of Allsopp’s. This seemingly unlikely situation can be explained partly by the very different attitudes to patent protection in Britain and in Germany combined with an apparent indifference to the significant business opportunity that the presence of a leading dye chemist presented to Allsopp’s. Although his work for the brewery remained largely proprietary, Griess’s discoveries in dye chemistry were exploited by the German dye industry, which quickly outpaced its British counterpart. One less well-known connection between brewing and synthetic dyes, and one that may further explain Allsopp’s attitude, is the use of synthetic dyes in identifying microorganisms—the perennial preoccupation of brewers seeking to maintain yield and quality. Developments of Griess’s original work continue to be applied to many areas of science and technology.

That’s just the abstract, of course, but you can read the whole article online.