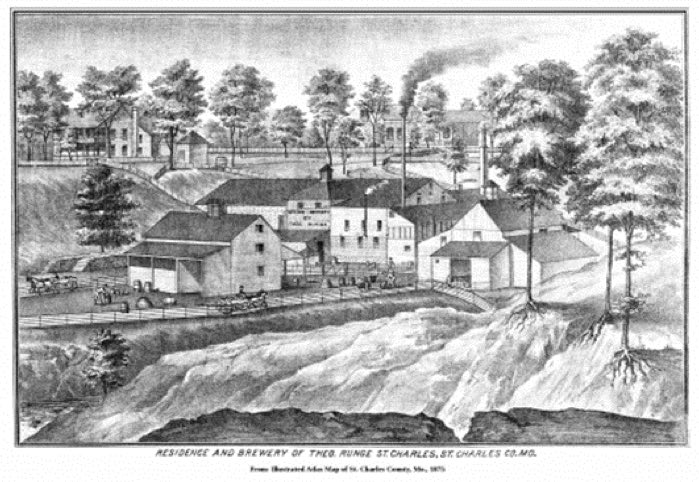

Today is the birthday of Christian Heuser (January 24, 1808-June 13, 1866). He was born in Rheinland, Prussia (which today is part of Germany). He came to the U.S. in the late 1840s, settling in St. Charles, Missouri. In 1852, he founded the Spring Brewery. When he passed away in 1866, the brewery passed to his son-in-law, Theodore Runge, who ran it for over two decades before selling it to Jacob Moerschel. The brewery continued on under a variety of owners and names — such as the Fischbach Brewery, the Skooner Brewing, the Van Dyke Brewery, and Cardinal Brewing — before closing for good in 1970.

There’s very little information about Heuser. All I could find was that he was born in Evangelisch, Ruenderoth, in Rheinland, and then nothing until 1842. In that year, he had a daughter born, and his wife appears to be “A. Margaret,” which isn’t much to go on.