Today is the 43rd birthday of Jeremy Danner, who when I met him was the ambassador brewer for Boulevard Brewing. These days he’s on the team at 4 Hands Brewing in St. Louis, though he’s still in KC. Jeremy’s a Kansas City native who worked at several bars, restaurants and breweries, working his way up to his present job with Boulevard. Given that his love affair began on his 21st birthday, that means this is his 19th beer year anniversary, too. Plus Jeremy’s an unabashed goat lover and social media diva, making him an entertaining force to be reckoned with. After several years knowing Jeremy only online, I finally ran into Jeremy in Denver and a number of times since. Join me wishing Jeremy a very happy birthday.

[Note: last two photos purloined from Facebook.]

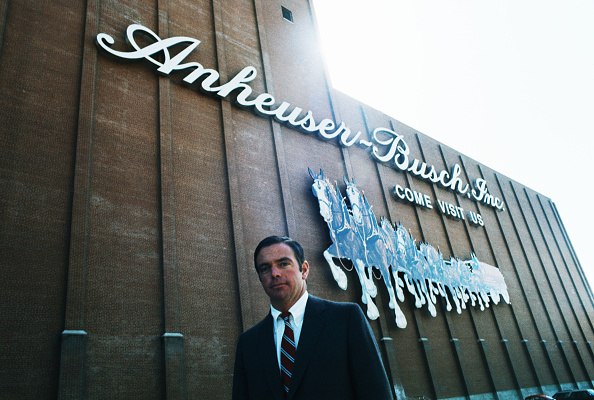

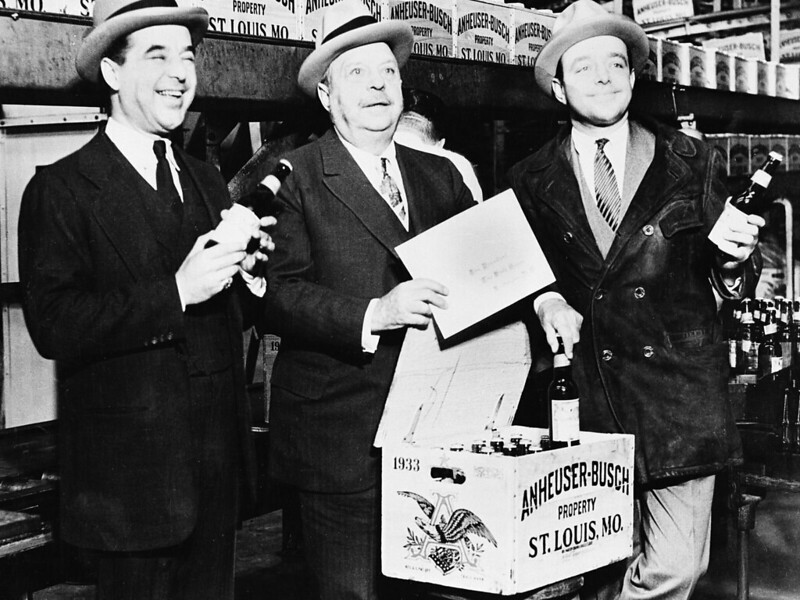

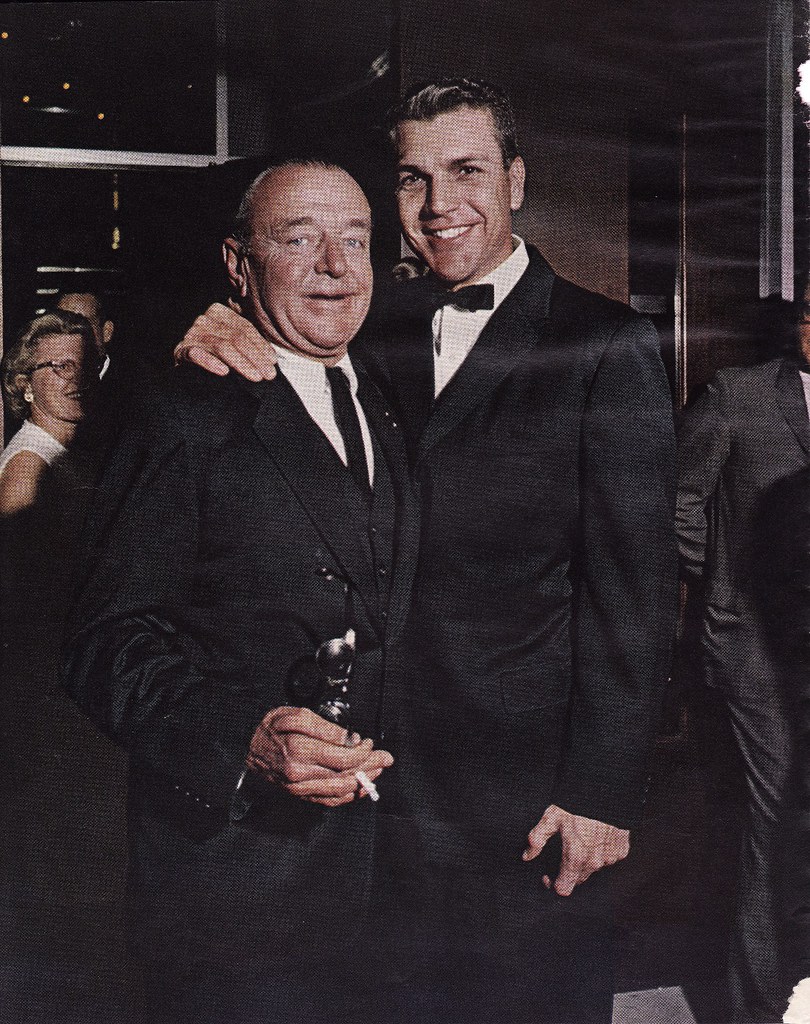

To celebrate production of the ten millionth barrel of beer, August A. Busch Jr. (right) and his son August III share a toast with other officials of the company on December 15, 1964.

To celebrate production of the ten millionth barrel of beer, August A. Busch Jr. (right) and his son August III share a toast with other officials of the company on December 15, 1964.