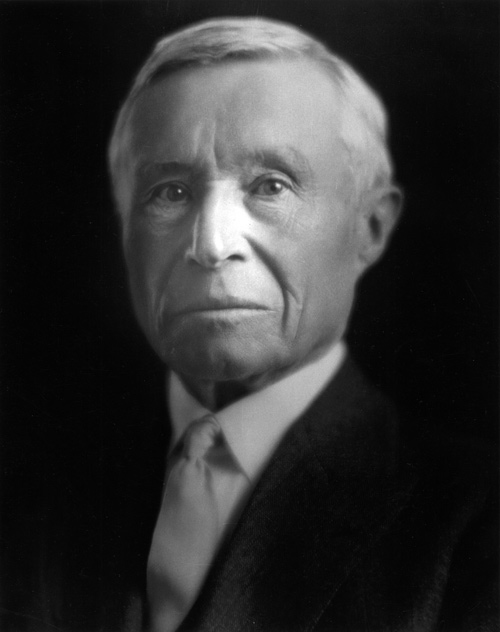

Today is the birthday of Frank J. Selinger (July 8, 1914-June 15, 2000). He was born in Philadelphia and was trained as a chemist and later became a brewmaster, first with the Esslinger Brewing Co. in Philadelphia, but later with the Burger Brewing Co. and Anheuser-Busch. But in 1977, he accepted the position of CEO for Schlitz Brewing and even appeared in television commercials for them in the early 1980s.

Here’s an obituary of Sellinger, from the Williamsburg Daily Press:

Francis J. Sellinger, a former brewing executive in Milwaukee, St. Louis, Cincinnati and Philadelphia, died Thursday, June 15, 2000, at Williamsburg Community Hospital. He was 85.

A native of Philadelphia, Mr. Sellinger graduated in 1936 with a degree in chemistry from St. Joseph’s College in Philadelphia. According to his son, Joseph Sellinger, he initially wanted to become a doctor but took a job in a brewery in order to help support his family. He began his career in the brewing industry in 1936 as chief chemist and assistant brewmaster with the Esslinger Brewing Co. in Philadelphia. In 1952, he joined the Burger Brewing Co. in Cincinnati, and he became vice president and general manager in 1956.

Mr. Sellinger joined Anheuser-Busch Inc. in St. Louis, Mo., in 1964. During his 14 years with the company, he held many senior executive positions, including vice president of engineering, and was a key figure in the company’s rapid brewery expansion during the 1970s, with the construction of breweries in Columbus, Ohio; Jacksonville, Fla.; Merrimack, N.H.; Williamsburg, Va.; and Fairfield, Calif. Mr. Sellinger was also heavily involved in the promotion of new technological advances within the company.

“He was the one that understood the direction the economics of the industry were going in,” said Patrick Stokes, president of Anheuser-Busch Inc.

He also played a key role in the development of the company’s Busch Gardens-The Old Country theme park and the Kingsmill Residential Community and Resort, both in Williamsburg.

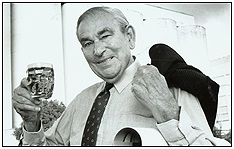

In 1978, he became the vice chairman and chief executive officer of Schlitz Brewing Co. in Milwaukee. According to Joseph Sellinger, one of his first tasks at Schlitz was to turn the image of the company around. He worked to accomplish this by returning the company to a traditional brewing process. In addition, Mr. Sellinger appeared in the “Taste My Schlitz” television advertising campaign that began in 1978. Joseph Sellinger said that the locales for his father’s commercials ranged from barley fields to bars. Mr. Sellinger continued his career at Schlitz until his retirement in 1983 to Kingsmill in Williamsburg.

After his retirement, Mr. Sellinger became involved with the Anheuser-Busch Golf Classic, now the Michelob Golf Classic, and worked for St. Bede’s Catholic Church.

Mr. Sellinger will be remembered for his integrity, caring and generosity toward his family, friends and employees. He came from very humble beginnings, said Joseph Sellinger, yet gave so much to others.

And this is from the New York time, from March 1, 1981, an article by Ray Kenny entitled “Trying to Stop the Flight from Schlitz.”

MILWAUKEE SHORTLY after Frank J. Sellinger went to work at the Jos. Schlitz Brewing Company in November 1977, he faced the first in a long list of problems.

A daughter, who then lived on the West Coast, telephoned and confessed: “Daddy, I don’t like that beer.” She had a lot of company. Schlitz, which had reformulated its flagship brand in a disastrous economy move in the 70’s, has been fighting a steady decline in sales ever since. Earnings plunged from almost $50 million five years ago to a $50.6 million loss in 1979 when it sold its newest brewery.

Said Mr. Sellinger: “I told my daughter, ‘Honey, do me a favor. Try Schlitz Malt Liquor. If you still don’t like it, go back to Budweiser.'”

After all, Mr. Sellinger said, “Anheuser-Busch put bread and butter on the Sellinger table for a lot of years.” Mr. Sellinger was an executive there all those years. Now, as vice chairman and chief executive at Schlitz charged with getting people to drink Schlitz again, he has reworked its taste, pitted it against the major beers in taste competitions televised live and gone on television commercials himself as the company’s down-to-earth pitchman. He has also pared expenses, cut excess brewing capacity and tightened quality control.

For all that, Schlitz is still losing sales position. In its best year, 1976, the company sold 24.2 million barrels. In 1980, shipments declined 11 percent on the year, to 15 million barrels. The company lost its fingertip hold on third place in the industry, behind the Anheuser-Busch Companies, which sold 50.2 million barrels in 1980, and the Miller Brewing Company, a subsidiary of Philip Morris Inc., which shipped 37.3 million barrels last year. Schlitz dropped to fourth place, behind its crosstown rival, Pabst, which shipped 15.1 million barrels.

“This company faced the toughest marketing problem you’ve ever seen,” an outside director said. “Beer drinkers are intensely loyal and we drove them away. Getting them to switch back is a horrendous challenge.”

Despite the continued falling sales, the company managed to show a profit last year of $27 million, or 93 cents a share, on revenues of $1 billion. Mr. Sellinger’s efforts apparently have paid off, along with gains by Schlitz’s container division and some profits attributed to nonoperating areas of the business. Clearly, corporate executives and members of the Uihlein (rhymes with E-line) family, who continue to hold the controlling interest in the company, were buoyed by the earnings swing.

“When sales are falling, the first thing you do is arrest the decline,” Mr. Sellinger said. “We’ve slowed things down but it’s too early to tell whether we’ve turned it around. Ask me again in June.”

Mr. Sellinger, 66, was named vice chairman and chief executive officer at Schlitz last April after coming on board in 1977 as president. One of the first things he did in an attempt to slow falling sales was to formulate what he calls “one helluva good brew.” He assembled technical personnel and urged them to create a flagship beer that would appeal to the eye as well as the taste.

“It has to look good,” he said. “Americans drink with their eyes. Beer has to be rich in flavor and hold its head. “There is just so much you can do. You can increase the barley malt and change the amount of hopping – the ratio of hops to corn. But the malt is the soul of the beer.

“From January of 1978 until July, we conducted test after test after test. Finally, we all agreed, and I’ll tell you, if we can get people to taste the beer, we’ll keep ’em.”

Then he sought to improve quality control. “If the quality guy at a plant says it doesn’t go, it doesn’t go,” he said. “He reports to headquarters, not to the plant manager, and if that means we dump 5,000 cans because of high air content, then we dump 5,000 cans.”

Mr. Sellinger pared the payroll to 6,100 employees, eliminating 800 to 1,000 jobs. “I believe in paying fair wages,” he said, “but I can’t afford two workers for one job. We eliminated a lot of people. We sacrificed a few for the good of the many.”

As for expenses, he said, “We had grown fat. Lax. I mean, how many WATS lines do you really need? How many copies do you have to make? There a million ways to save.”

He cut deeply into excess capacity when he closed the company’s newest brewery – a six-year-old facility in Syracuse, N.Y., in 1979. The move, together with the closing of a small brewery in Honolulu, trimmed production capacity by 5.4 million barrels. But the company is still swimming in capacity. Last year it was capable of turning out 25.6 million barrels while it sold 15 million.

A year ago, the Syracuse plant was sold to Anheuser-Busch for $100 million. The company absorbed a $44.3 million loss in the process. “That was a beautiful brewery,” Mr. Sellinger said, “but it was an albatross. That doesn’t mean the decision to build it wasn’t right at the time. If your sales trend is a plus 12 percent a year, then you know that in three and a half years – the time it takes to construct a brewery – you will need so much beer to satisfy demand. The 1974 trend told us we would have to spend $157 million for the beer we would need by 1977.”

B REWERIES are built with the wholesalers in mind, Mr. Sellinger said. “We pressure them to sell Schlitz and they want to know whether Schlitz will have the beer if the business continues. We can’t say, ‘we have no beer.’ That takes all their incentive away.”

But if the customers leave, there’s no need for a brewery. “That’s the chance business takes constantly,” Mr. Sellinger said. “Look at our friends at Miller. Their trend line has been a plus 24 percent a year, but now it’s 3 1/2 percent.” Between 1954 and 1964, no breweries were built in the United States, the Schlitz chief recalled.

“Only Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz had the guts to borrow the money at 9.2 percent interest and build new plants. We didn’t have a ‘cash cow,’ ” he said, using his favorite description for Philip Morris. “What would Miller’s profit be if they paid even 8 percent interest on that Philip Morris investment?”

Schlitz embarked on an expensive campaign featuring live taste tests on television, pitting its product, at various times, against Miller High Life and Anheuser’s Budweiser and Michelob. Half the 100 Budweiser drinkers pulled the lever for Schlitz in one test supervised by Tommy Bell, a widely recognized referee in the National Football League. Other scores were respectable. But some critics said that the nature of the tests gave Schlitz the advantage. (Since the participants in a given test were all, say, Budweiser drinkers, Schlitz could claim victory if any favored its beer.)

Concluded Joseph Doyle, a brewing industry analyst at Smith Barney Harris Upham & Company: “All the media coverage (of the taste tests) is giving Schlitz a big bang for their buck. I’d count the campaign a huge success if it arrests the decline of the brand, and it looks like it is doing that.”

The company trumpeted the results in follow-up newspaper ads, but there are no current plans to continue the live taste tests. Nevertheless, Mr. Sellinger’s desk is piled with letters and comments. “Here’s one from five students at Holy Cross – Bud drinkers – who have started a Tommy Bell/Schlitz fan club,” he said. “The young drinkers are the ones you want to win.”

The company has not disclosed sales figures related to the television campaign but some distributors reported sales gains. “We doubled our January sales in the first week,” after the commercials began, reported Jack Lewis, a distributor in Cleveland. Joe Scheurer, in Philadelphia, said his sales were up 10 percent. Other distributors reported gains.

Mr. Sellinger, who prefers the term “beer tasting” to beer guzzling, will drink to that.

Here’s one of Sellinger’s TV ads, this one from 1981.

And here’s another one.

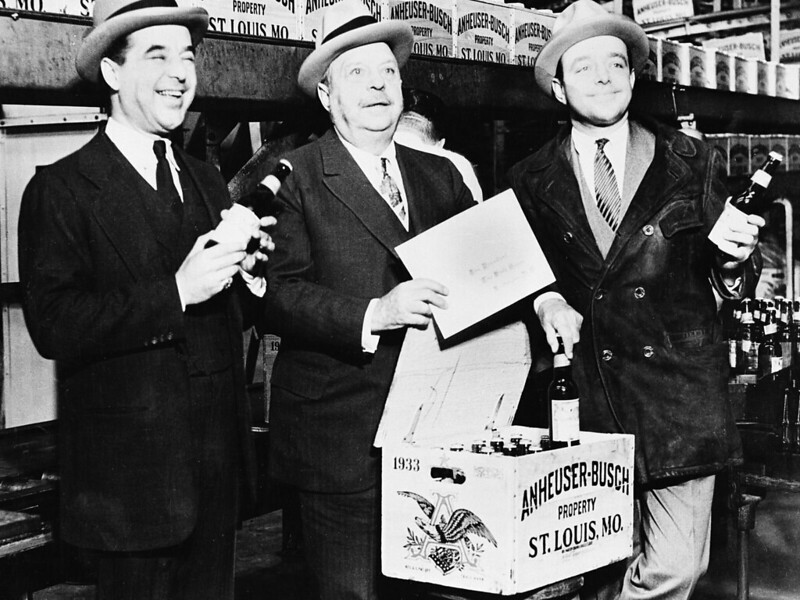

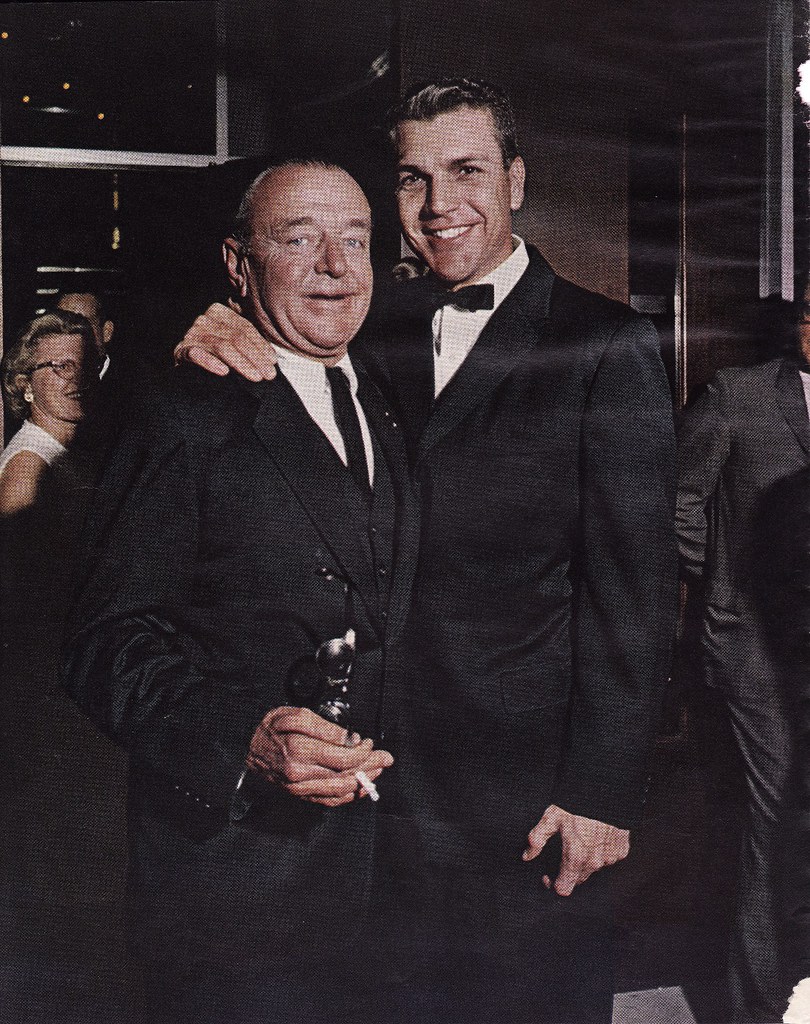

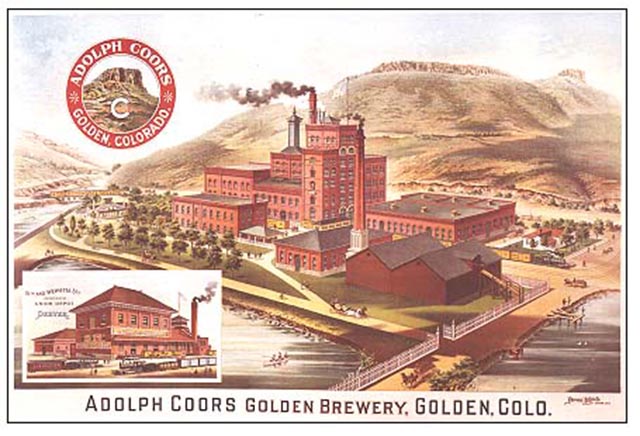

To celebrate production of the ten millionth barrel of beer, August A. Busch Jr. (right) and his son August III share a toast with other officials of the company on December 15, 1964.

To celebrate production of the ten millionth barrel of beer, August A. Busch Jr. (right) and his son August III share a toast with other officials of the company on December 15, 1964.

Bryan and me at GABf in 2024.

Bryan and me at GABf in 2024.