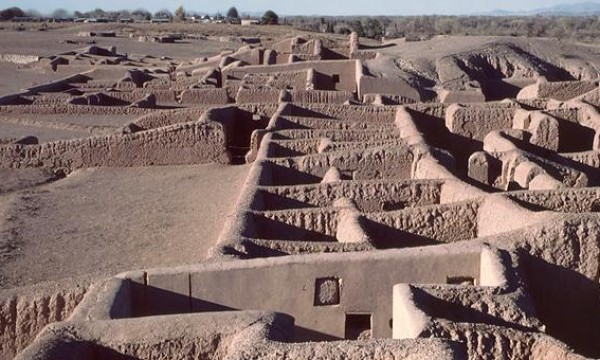

The ancient city of Casas Grandes (a.k.a. Paquimé) is “a prehistoric archaeological site in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua. Construction of the site is attributed to the Mogollon culture. Casas Grandes has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.” It once was home to at least 3,000 people in the 14th century, and was most likely a trade center in its heyday. It was first excavated in the 1950s, and initial finds included hundreds of human remains. It was inhabbited beginning around 1130 CE and hit its peak after 1350 CE, but was inexplicably abandoned a century later by 1450 CE. It’s “regarded as one of the most significant Mogollon archaeological zones in the northwestern Mexico region.”

So you’d think it was pretty well mined for what could be learned from the ancient city. But a team of archeologists from the University of Calgary led by Dr. Anne Katzenberg is using new technologies to examine the plaque on the teeth of hundred sets of human remains, specifically what they call “tooth calculus,” which she says is “fossilized tooth tartar.”

Western Digs, which “is a science news site that investigates the archaeology, anthropology, and paleontology of the American West,” continues the story in First Evidence of Corn Beer in Southwest Discovered on Teeth From Ancient Burials:

“If teeth aren’t cleaned regularly, then the tartar, which can trap pretty much anything in it, such as algae, plants, fungus, or fibers, will slowly mineralize with everything stuck in it and turn into calculus, while the microremains turn into microfossils.”

To get at this microscopic evidence, the team recovered tartar from the remains of 110 people found within the ancient city and from other sites in the Casas Grandes River valley, all buried between 700 and 1450 CE.

Of those 110 samples, 63 yielded some sort of microscopic remains.

But what they’ve concluded is that there was a lot of corn beer being consumed, but more importantly “what archaeologists say is the first conclusive evidence of corn beer in the Greater Southwest.”

Here’s more from First Evidence of Corn Beer in Southwest Discovered on Teeth From Ancient Burials:

Three of the samples revealed granules of maize that bore the unmistakable signs of fermentation, he said — including swelling and fragmentation caused by being heated at three distinct temperatures, and striations created by the fermenting process.

These bloated, broken grains seem to be the result of making chicha — a corn beer whose use has been recorded in Central and South America for as much as 5,000 years, King said.

In those cultures, brewing and consuming chicha is thought to have held ceremonial value, but it may have held other functions as well, he noted.

“We don’t have enough information to determine [chicha’s] use,” King said.

“Based on ethnographic accounts, we default to ‘ritual’, although I always think that’s a cop-out answer.

“We know modern groups used corn beer or similar drinks in religious ceremonies, so that’s all we can go off of.”

In addition, King noted, the burial contexts of the samples haven’t yet been analyzed, so archaeologists can’t yet draw conclusions about whether beer consumption was limited, for example, to a certain social class.

Moreover, he added, this is the first “substantial evidence” of corn beer in the Greater Southwest, so it’s possible that chicha may have served a different function in Casas Grandes than it did in Mesoamerica.

When it comes to beer in the southwestern archaeological record, he said, “almost nothing exists for northern Mexico or the American Southwest. The results we posted may be the first of their kind for this region.”

King’s new findings, then, raise the question of how the custom of brewing corn beer arrived at Casas Grandes, as well as when, and by whom.

“The best archaeological evidence we have for corn beer and other alcoholic drinks comes from Peru or Mesoamerica,” King said.

“So, if anything, the idea for corn fermentation came up from the south, but that is still conjecture at this point.”

As for when beer came to town, his findings do provide some insights.

His team studied teeth dating back as far as the year 700, but the fermented granules were only detected on remains dated to the so-called Medio Period of Casas Grandes — a cultural heyday that spanned from about 1200 CE to 1450 CE — suggesting that chicha might have been a relatively recent phenomenon.

“Our results show that maize was used throughout various time periods, but evidence for maize fermentation only comes from the Medio period,” he said.

“This is not to say such use did not exist in the [earlier] period, only that our results don’t currently support that idea.”

But whether it was brewed, chewed, or cooked, the corn of Casas Grandes may, in time, teach us volumes, not just about diet, but also about the social interactions that shaped one of the most important cultural crossroads in ancient North America.

“The continuity of maize use throughout the two time periods is important,” King said.

“It may suggest a continuity of people, thereby supporting an in situ development.

“Turning maize into beer during the Medio period, however, could suggest an influx of new ideas — or perhaps even people — during that time, which might indicate outside influence — either foreigners coming to Casas Grandes, or locals traveling and coming back with new ideas.”