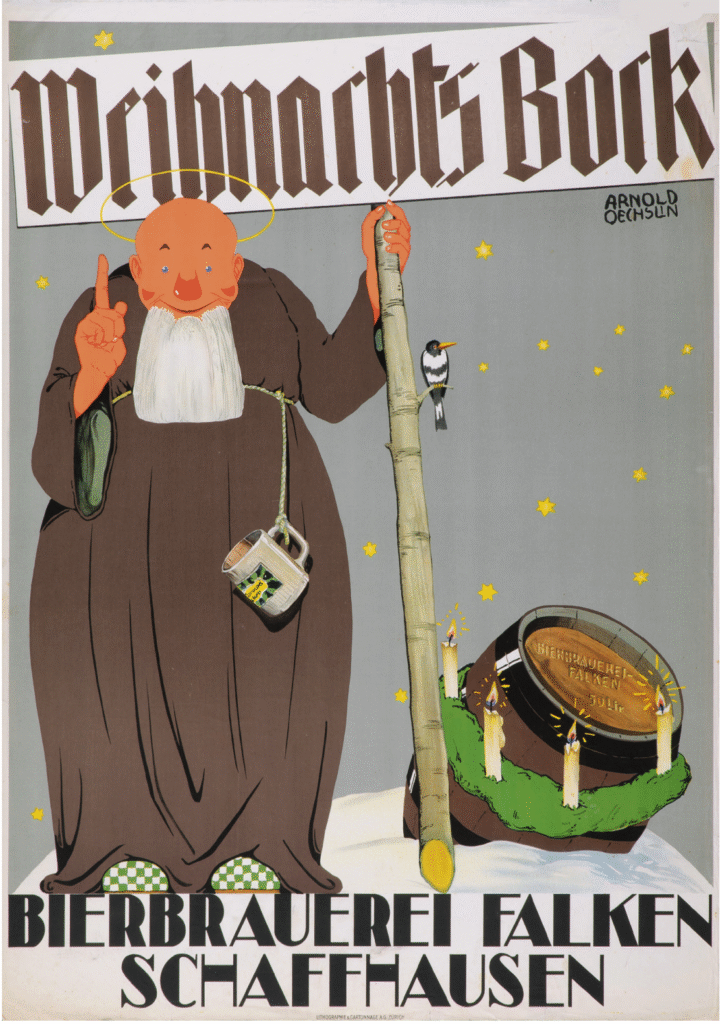

Last year I decided to concentrate on Bock ads. Bock, of course, may have originated in Germany, in the town of Einbeck. Because many 19th century American breweries were founded by German immigrants, they offered a bock at certain times of the year, be it Spring, Easter, Lent, Christmas, or what have you. In a sense they were some of the first seasonal beers. “The style was later adopted in Bavaria by Munich brewers in the 17th century. Due to their Bavarian accent, citizens of Munich pronounced ‘Einbeck’ as ‘ein Bock’ (a billy goat), and thus the beer became known as ‘Bock.’ A goat often appears on bottle labels.” And presumably because they were special releases, many breweries went all out promoting them with beautiful artwork on posters and other advertising.

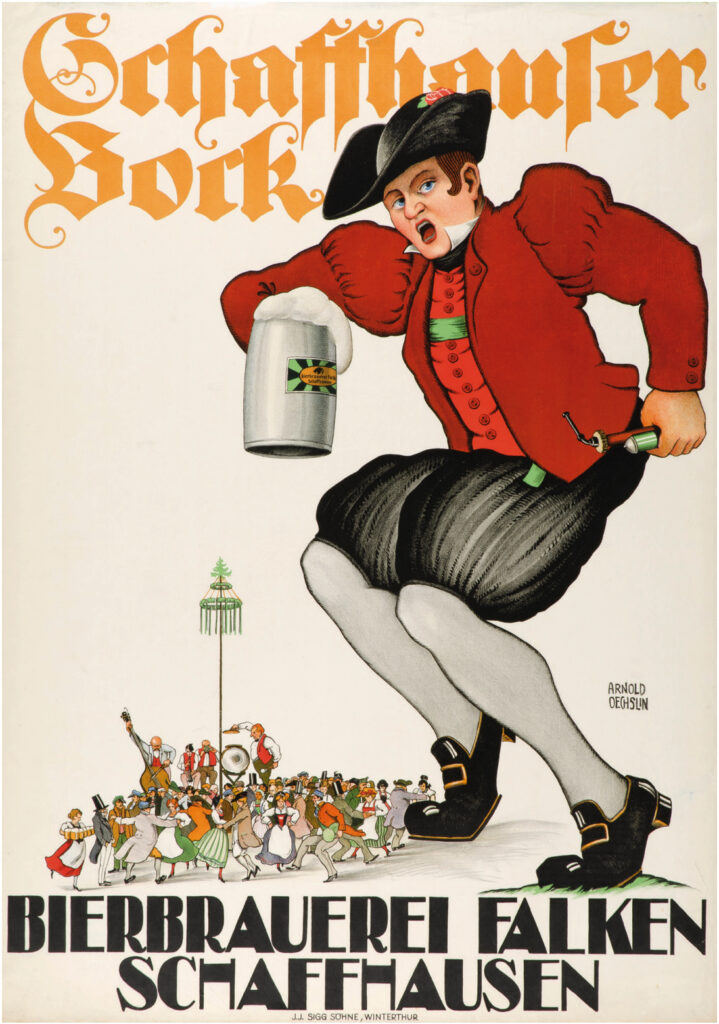

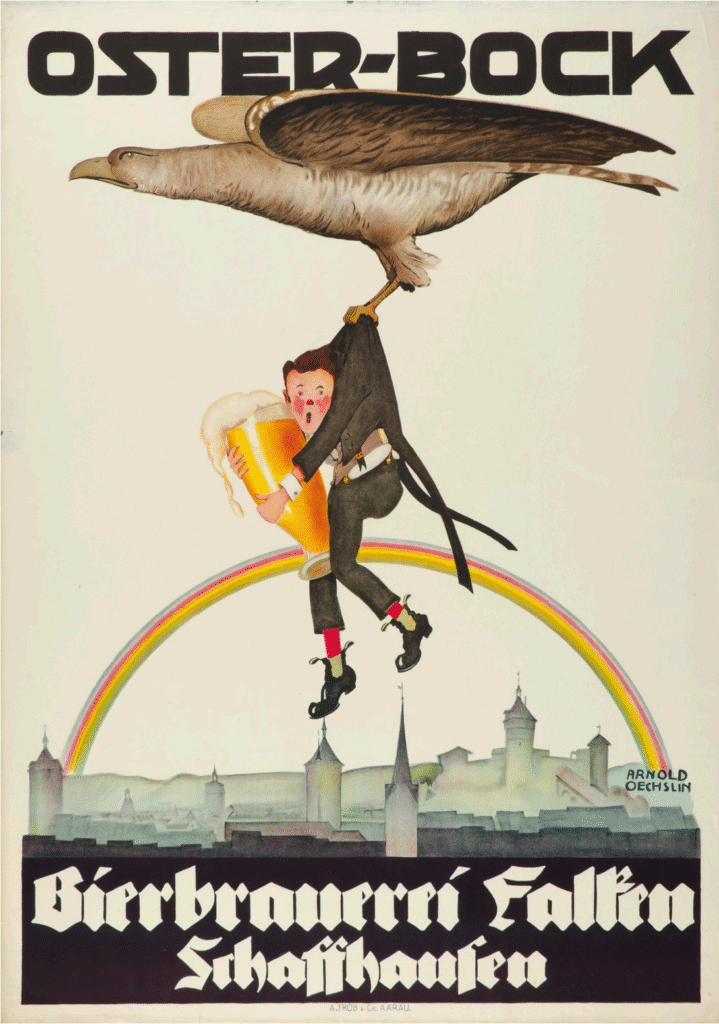

Wednesday’s poster is for Falken Schaffhauser’s Bock, and was published in 1932. This one was made for the Bierbrauerei Falken Schaffhausen, or Falcon Brewery, of Schaffhausen, Switzerland. The brewery was founded in 1799, and is still in business today, and is “considered the only independent brewery in the Schaffhausen region,” and is Switzerland’s 5th largest brewery. This one is for their Schaffhauser Bock and shows a giant man with a mug of beer. Below him is a village Maypole with a band playing while numerous couples dance. It was created by Swiss artist Arnold Oechslin.