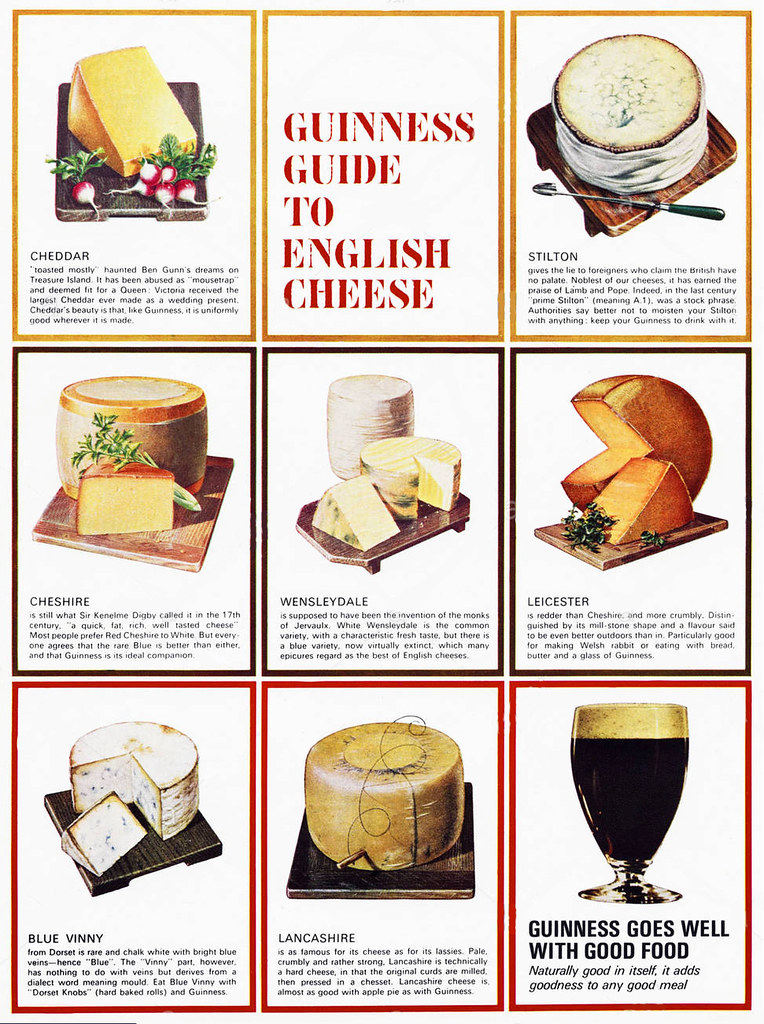

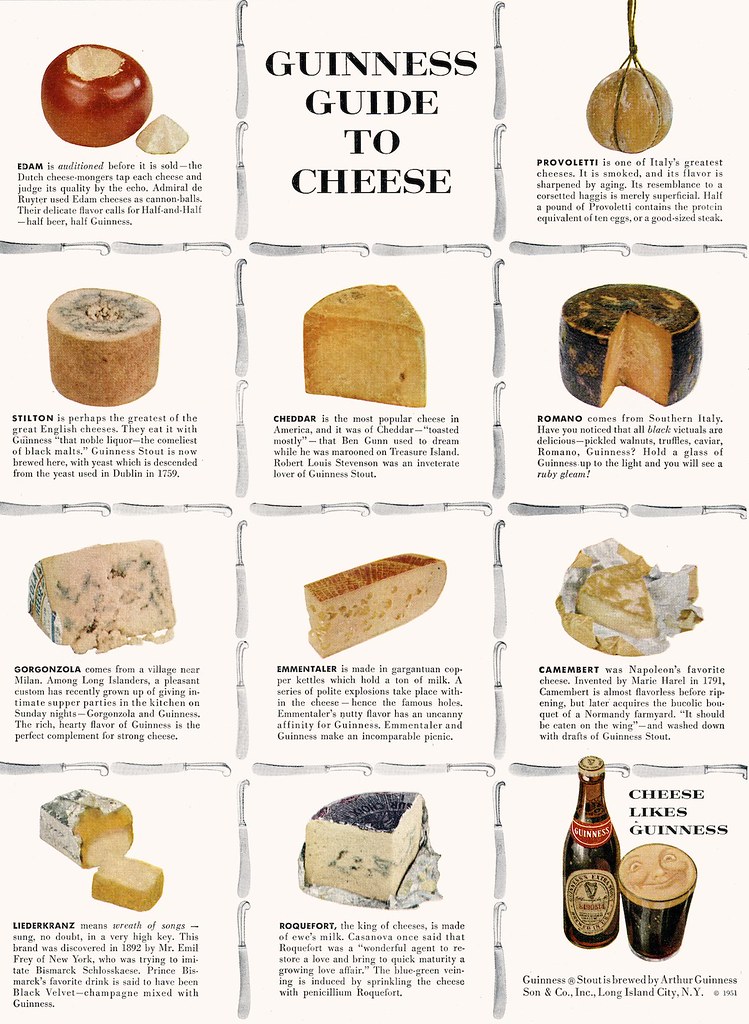

Wednesday’s ad is for Guinness, from 1965. While the best known Guinness ads were undoubtedly the ones created by John Gilroy, Guinness had other creative ads throughout the same period and afterward, too, which are often overlooked. In this ad, the “Guinness Guide to English Cheese,” seven different English cheeses are illustrated, each with a short description about them, and what foods to pair with them, not to mention how good a glass of Guinness will pair with each cheese.