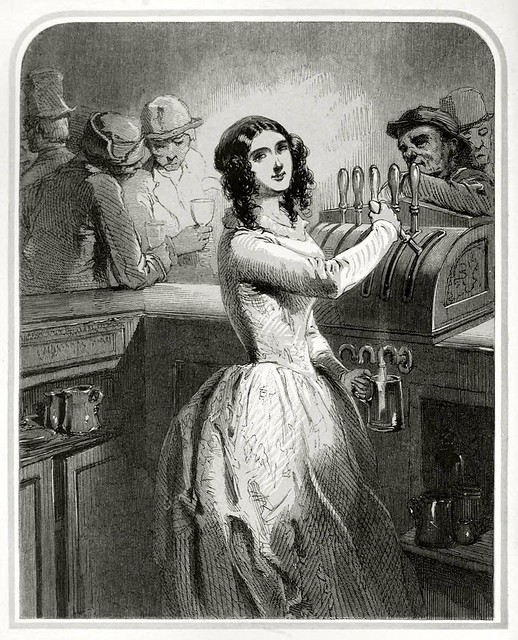

In 1849, a book described as “sketches of life and character, with illustrative essays by popular writers” was published by David Bogue in London. Entitled Gavarni in London , the name comes from the illustrations by French artist Paul Gavarni. They’re apparently drawings that Gavarni did in England, and there are a total of 23 of them, each with an essay by popular writers of the day. There were acrobats, street beggars, thieves along with scenes from the West End, Greenwich Fair and others. There was also one about a Barmaid, the female bartender in the mid-17th century. The Barmaid essay was written by J. Stirling Coyne, who was an English playwright who was similar to Jonathan Swift or Alexander Pope. Open Library has the whole book available online to read, or go straight to The Barmaid to see it in the original, or just read it here below Gavarni’s illustration of The Barmaid.

THE BARMAID

Who is she that sitteth in the shrine of the temple of Bacchus? — the Priestess of that ancient worship whose mysteries are celebrated in the Halls of Evans. Her brows are crowned with mint and juniper, and her shining tresses curl like the rind of the artfully peeled orange upon her polished shoulders; in her right hand she beareth a bowl of fragrant nectar, and in her left presseth a golden lemon; gas-lights burn brilliantly around her, and the rich odours of Geneva fill the air; pleasantly she smileth upon her customers through clouds of incense wafted from patrician Principes or plebeian Pickwicks, and tempereth the ardency of Cognac with mild modicums from the New River. A legion of kind familiar spirits obey her behests: hers are the refreshing fountains of Soda, and hers the gently-flowing waters of Carrara! Who asks her name? Who knows not the pretty Barmaid — the modem Hebe, whose champagne is not more intoxicating than her aeillades?

Like the moon she never shines with full lustre till night; then she comes out in all the fascinations of satin and small talk — bestowing, with perfect impartiality, a smile upon one admirer, a tender glance upon another, and a kind word or two upon a third; leaving each in the happy belief that he is himself the fortunate individual upon whom she has secretly bestowed her affections. She carries on a flirtation while concocting a sherry-cobbler, accepts a lover in the act of sweetening a glass of toddy, and even permits a gentle pressure of the hand when giving you change out of your sovereign. But all this is selon son metier — a mere matter of business with which the heart has nothing to do.

Thus the Barmaid seems to be a kind of moral salamander, living unharmed in the midst of the amorous furnace in which Destiny has placed her. Long habit has perhaps inured her o this state of insensibility, upon which her safety as well as her happiness depends; but we believe it is an established fact in her history that no Barmaid ever gave away her heart, or permitted it to be sponged from her fingers’ ends, across the counter.

It is during her soiree — when her little court is filled with Gents, swells, and loungers from the theatres, that the Barmaid’s triumph is at its height. Then in the plenitude of her power she flings hack saucy repartees to pert addresses, and generally — for she has the sympathies of her audience with her — turns the laugh against the fool who has the temerity to hazard a skirmish of wit with her.

She has a wonderful acquaintance with all the floating topics of the day, and talks with as much confidence of Sir Robert’s great speech, and Sibthorpe’s last joke as a parliamentary reporter. She thinks the Guards “delightful fellows,” and declares her decided partiality for moustaches; she has a’settled conviction that Jullien is “a duck,” and considers the two mounted Blues at the Horse Guards models of manly and equine beauty.

These, however, are but the general outlines of the portrait : the Barmaid, like the chameleon, takes her local colour from the character of her visitors, and insensibly adopts the professional manners and language of the class in society with which she associates. Thus, at Limehouse she is marine, and in Albany Street military; in the neighbourhood of the Temple, and all about Chancery Lane she talks of sittings, and after-sittings — of caveats, pleas, and demurrers, with the gravity of an old Chancery barrister. In the vicinity of Covent Garden, along the Strand, and up the Haymarket, the Barmaid discourses most eloquently upon things theatrical; she has all the scandal of the green-rooms “by express,” and knows the name of every danseuse who gives Lord So-and-so a seat in her brougham in Hyde Park. She calls Mr. Macready “Mac,” and Buckstone “little Bucky;” she has, moreover, a white satin slipper of Taglioni’s, and a presentation copy of Baugniet’s admirable lithographic portrait of Paul Bedford, with the great creature’s autograph at foot, framed and hung up in the bar. In the Sporting Houses the Barmaid affects the Turf, and confesses, privately, that she has no objection to the Ring. She knows, the names of the favourites for the Derby and Leger, and backs them all round for any amount of gloves, handkerchiefs, ribbons, and other small wares, knowing that if she wins, she will be paid; and, if she loses, she never insults a gentleman by mentioning it. Within the circuit of half-a-mile of the London University the Barmaid is a blue; and if you be not on your guard, you may chance to get floored with a quotation from Horace, or a problem from Euclid. Besides these, there is the medical student Barmaid — near the hospitals; and the musical Barmaid — near the operas; and the artist Barmaid — anywhere; and the newspaper Barmaid — everywhere; with fifty others in various professions, who having picked up a smattering of the subjects they hear continually discussed, talk upon them as fluently, and sometimes quite as sensibly, as their instructors.

Having sketched the Barmaid at home, let us now present her to our readers as she appears abroad. True, her enjoyments beyond the narrow limits of the bar, and that mysterious little back parlour behind it, have been few; she has lived all her life amidst the grimy bricks and tiles of London. But she has an instinctive love of Nature implanted in her heart. The geranium in the little pot on her window-sill, and the flowers that she daily places in water on a shelf in the bar, are touching evidences that her heart has not lost its freshness in the withering atmosphere in which it has been placed.

When her periodical holiday arrives — that anxiously looked-for happy

The Saturday and Monday” —

how joyfully does she prepare for an excursion with “the young man that keeps her company” to Greenwich, or Hampstead, or Rosherville; but most she delights in a trip to Richmond by water. Seldom beats a happier heart than the young Barmaid’s on a fine summer’s morning, when, with a delicious consciousness of liberty — that only those whose patrimony is servitude can taste — she hurries, with her equally happy lover, on board “The Vivid” steamer at Hungerford-pier — trembling lest they should be late, although they are full twenty minutes before the time of starting. During the voyage up, she is in raptures with every object she sees; — the winding banks — the beautiful villas, peeping through thick foliage — the green aits — and the graceful swans, whose snowy plumage acquires a dazzling splendour as they glide in the dark shadow of the overhanging shore. Everything, in short, is brighter and fairer than ever it appeared before. Then there is the landing, and the walk up the hill to the Park — where, seated under an umbrageous chestnut-tree, she gaily unpacks her handbasket, and produces her little feast. Were ever sandwiches so delicious! And the snowy napkin for a table-cloth; and the salt in a wooden lemon, unscrewing at the equator — the prize of some dexterous hand at the popular game of “three throws a penny;” and the morsel of cheese in the corner of an old newspaper; and the white roll; and the something — in the very bottom of the basket, carefully concealed from view — which must not be seen till the fitting moment arrives — and which, after the sandwiches have been dispatched, and a good deal of coaxing and coquetting has been performed, is brought forth, and proves to be a Lazenby’s sauce bottle, full to the cork with — what do you think? — real French brandy — the very best pale we engage too. Of course this cleverly managed little incident gives occasion for fresh laughter, and the lover begins to fancy how pleasant it would be to have a wife who could feel so much solicitude for his comforts; and this thought sinks into his heart as the brandy sinks in the flask; and by the time they have got on board “The Vivid” on their return, he has almost made up his mind to pop the interesting question.

We will not follow the pair to the reserved seat they have secured in a quiet comer of the deck, for there are little mysteries even in the heart of a Barmaid which we hold inviolably sacred. All we are at liberty to divulge is, that the conversation must be deeply interesting; for, when a gruff voice shouts — “Now then! Hungerford! Who ‘s for Hungerford?” as the steamer slowly approaches the pier, she raises her head with the expression of one who has been disturbed from a pleasing dream ; and looking around her exclaims — “Dear me! I declare we’re at Hungerford already!”

“A change comes o’er the spirit of my dream.” — Five years have passed away the girl has become a matron — the pretty Barmaid has ripened into a handsome Hostess. She now stands behind her own bar, the undisputed mistress of her little realm; waiters tremble at her nod, and enamoured Gents get intoxicated upon her smiles. Time has mellowed, but not impaired her beauty — at least not in the estimation of those who measure feminine beauty by the standard of Reubens. The roses on her cheeks have perhaps taken a deeper tint — her abundant hair, wandering no longer in ringlets over her neck, is clustered beneath a cap of the most becoming fashion — the light robe is replaced by the glossy black satin — and a massive gold chain depends from her neck, where the plain ribbon hung before; but she is still the same frank, lively, and kind creature that we always knew her. The Hostess, indeed, is but the perfected Barmaid; — to whose numerous admirers we respectfully dedicate this sketch.

Jay, an excellent piece indeed. I’ve seen extracts but not the full essay. Let’s imagine an 1800’s reader of a notice (review) of this book, one with a particular interest in beer and its characteristics, wrote to the paper in which the review appeared. It might go something like this:

“….I write to comment on the quite remarkable piece on the barmaid by Mr. Coyne in [full description of book] which you noticed in the last issue. Sharp-eyed and endowed of a certain sensitivity, he is. But where is the barmaid of the breweries district, who could declaim as to the qualities (and too often, lack thereof) of the ales and porter of the divers brewers of this town? A barmaid such as this would be most valuable to the beer-man, that is, a man who prizes flavour and quality above quantity or other extraneous considerations? With the benefit of her counsel, a hard-earned sovereign needn’t be passed through the hand-pulls to be wasted on inferior brewages. To the patron who cares foremost about the soundness and flavour of malt liquors, such a barmaid would stand above all others. Charm and deportment are not unimportant, but to the undersigned pale in significance to a badly kept or muddy pot of ale or other beer. And so, the barmaid possessed of such invaluable knowledge is absent from Mr. Coyne’s panegyric. Perhaps, like the knowledge of art and music, he assumes such knowledge is the province of all barmaids anywhere in London. I daresay however that my experience in the houses of the great and smaller brewers, in whatever district you are pleased to name of the Capital, is quite otherwise. One might suppose Mr. Coyne does not fancy himself so much a good judge of beer as one of character and incident. And indeed of the latter he is most expert. Still, it is an opportunity lost, in the opinion of your humble correspondent”.

Gary

Nice addendum, Gary!