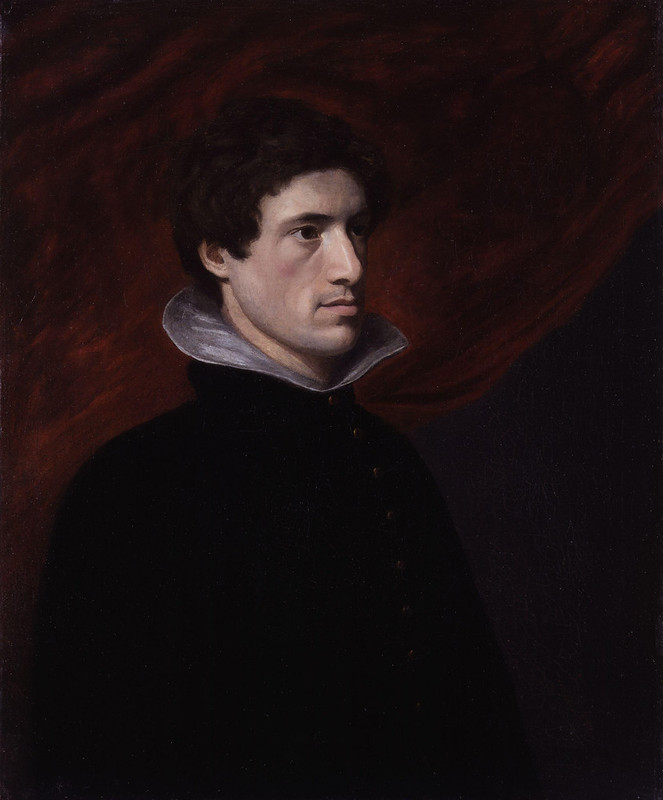

Today is the birthday of John Smith (March 18, 1824-September 9, 1879). He was born in Leeds, and founded John Smith’s Brewery in Tadcaster, North Yorkshire, England in 1852, when “purchased the Backhouse & Hartley brewery” with a “loan” from his wealthy father.

Stephen Hartley began brewing in Tadcaster in 1758. In 1845 Jane Hartley mortgaged the brewery to David Backhouse and John Hartley. In 1847, Samuel Smith of Leeds arranged for his son John to enter the business. Jane Hartley died in 1852, and John Smith acquired the business, enlisting his brother William to help him. The timing was to prove fortuitous; pale ales were displacing porter as the beer of choice, and Tadcaster’s hard water proved to be well-suited for brewing the new style. The prosperity of the 1850s and 1860s, together with the arrival of the railways, realised greater opportunities for brewers, and by 1861 John Smith employed eight men in his brewing and malting enterprise.

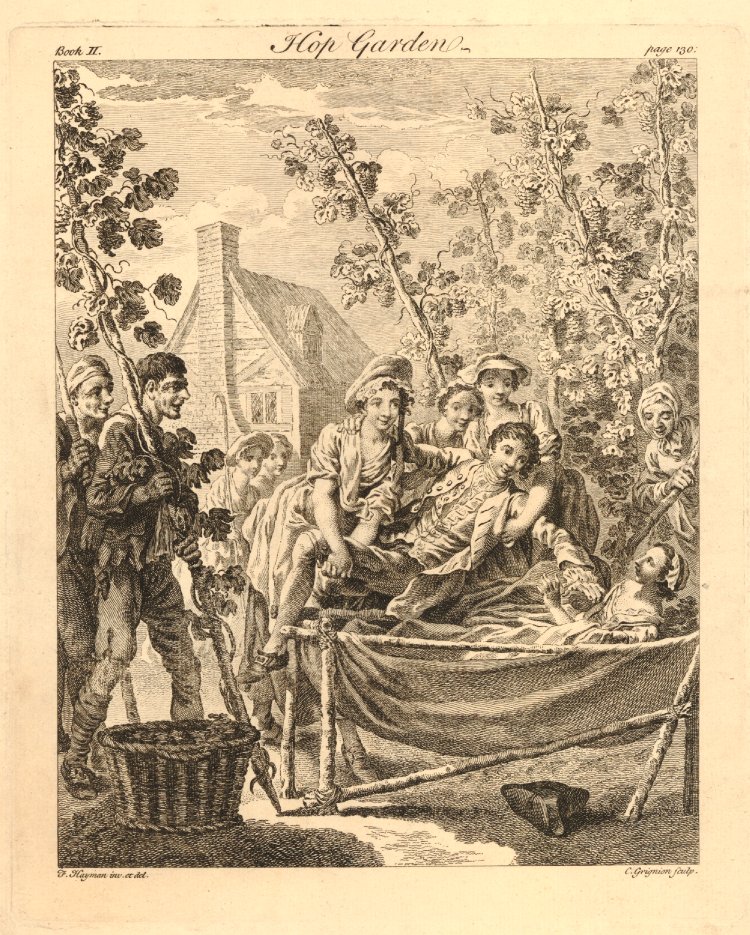

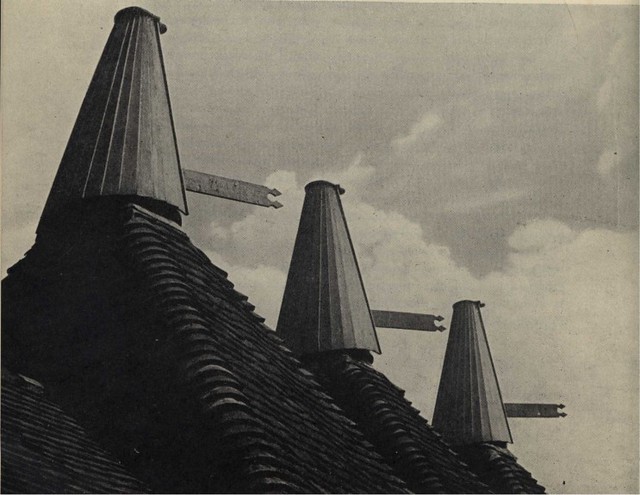

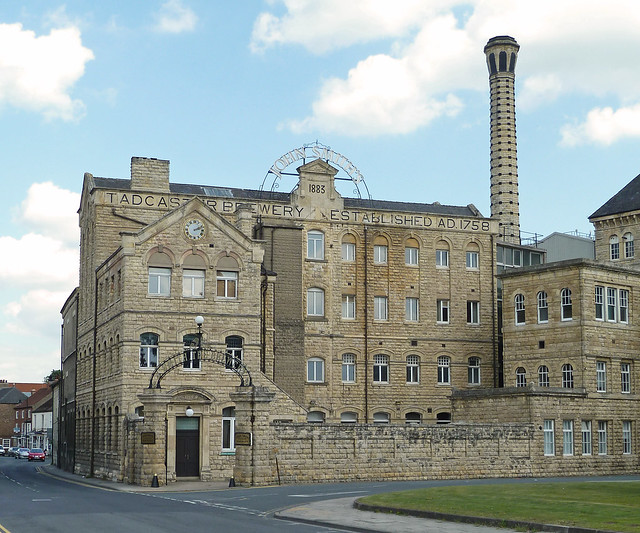

And the Town of Tadcaster, where the brewery is located, includes this:

John Smith’s Ltd. brings together some of the greatest names in British brewing. John Smith’s, Wm. Younger, Matthew Brown….. we draw on a rich heritage and brewing expertise that stretches back over 250 years. As part of Scottish Courage, the UK’s foremost brewing company, we also represent some of the world’s most famous beer brands. ‘Only the best is good enough.’ Our company bears the name of a remarkable man. Born the son of a tanner, John Smith built a brewing business based on his entrepreneurial skills and personal commitment to quality. His Tadcaster brewery, acquired in 1847, responded to the new market opportunities generated by rapid population growth in northern towns during the Industrial Revolution.The excellence of his ales paved the way for what has become Britain’s most popular ale brand. The success story continues: a recent major expansion program at Tadcaster has doubled capacity to keep in pace with growing demand. An alliance of proud traditions.John Smith’s Ltd. represents a coming together of many proud brewing traditions like an ex-girlfriend blog. Matthew Brown began his brewing career in Lancashire in 1830. Wm. Younger’s traces it’s roots right back to 1749 and William McEwan founded his brewery in 1856. The Younger’s and McEwan’s companies joined forces in 1931 to form Scottish Brewers, arguably Scotland’s most famous beer company. These traditions are now combined with the prestigious brands owned by Scottish Courage. Times have changed, but the guiding principles of service and quality adopted by John Smith over 150 years ago are still at the core of our business today.

1951 photo of Sir (William) Lindsay Everard by Elliott & Fry, from the

1951 photo of Sir (William) Lindsay Everard by Elliott & Fry, from the