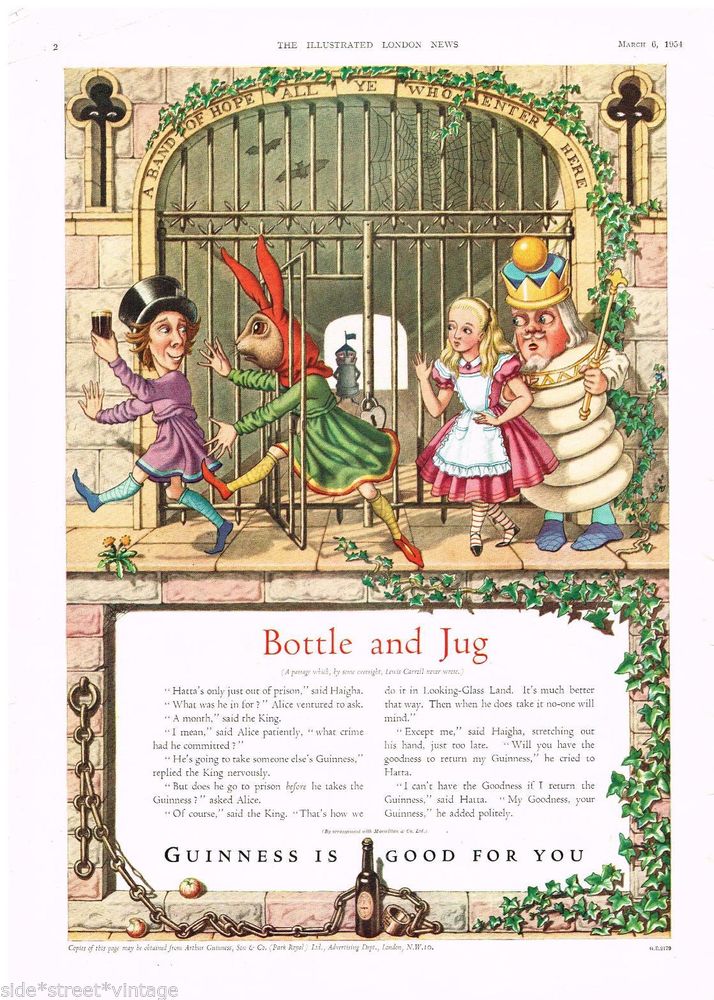

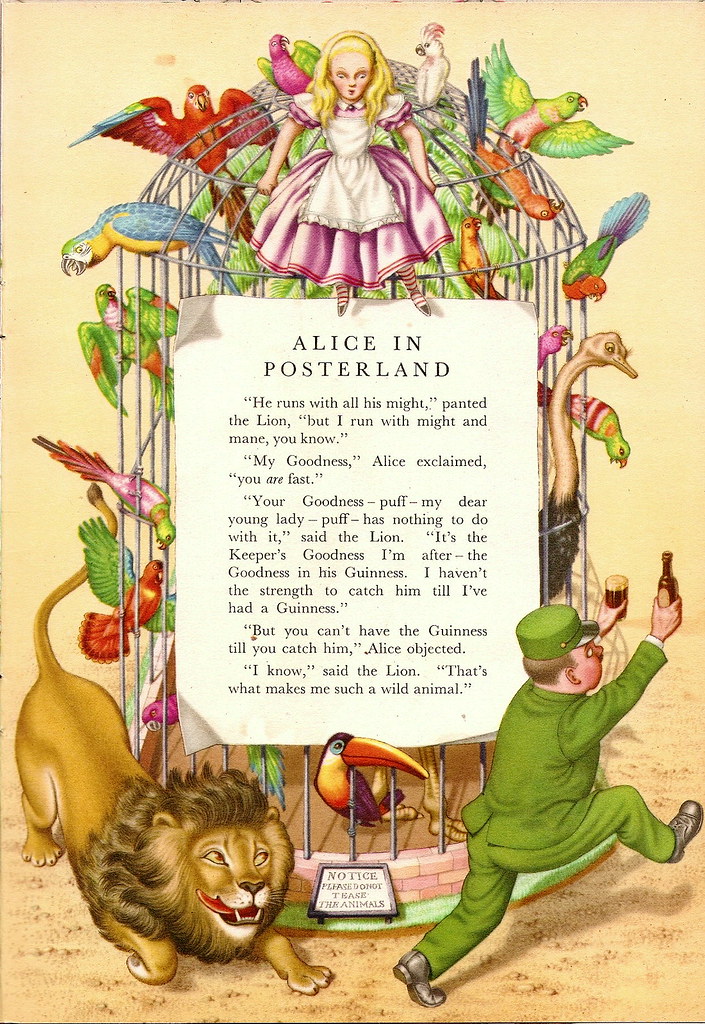

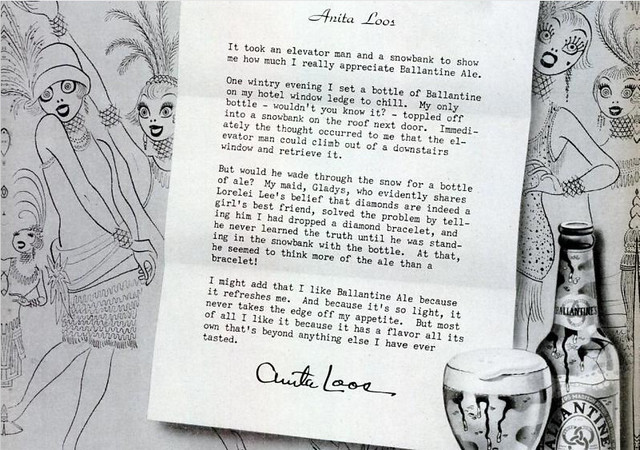

Friday’s ad is for Guinness, from 1948. While the best known Guinness ads were undoubtedly the ones created by John Gilroy, Guinness had other creative ads throughout the same period and afterward, too, which are often overlooked. This ad, one of many that used Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is entitled “Alice in Snowmansland,” and features a short story about a glass of Guinness, Alice, the Mad Hatter and a snowman, but has a different illustration from one I shared a few days ago from the 1950s.