![]()

Today is the birthday of William Cobbett (March 9, 1763-June 18, 1835). Wikipedia describes him as:

an English pamphleteer, farmer and journalist, who was born in Farnham, Surrey. He believed that reforming Parliament and abolishing the rotten boroughs would help to end the poverty of farm labourers, and he attacked the borough-mongers, sinecurists and “tax-eaters” relentlessly. He was also against the Corn Laws, a tax on imported grain. Early in his career, he was a loyalist supporter of King and Country: but later he joined and successfully publicised the radical movement, which led to the Reform Bill of 1832, and to his being elected in 1832 as one of the two MPs for the newly enfranchised borough of Oldham. Although he was not a Catholic, he became a fiery advocate of Catholic Emancipation in Britain. Through the seeming contradictions in Cobbett’s life, his opposition to authority stayed constant. He wrote many polemics, on subjects from political reform to religion, but is best known for his book from 1830, Rural Rides, which is still in print today.

An oil painting of William Cobbett, possibly by George Cooke, from

c. 1831, which hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Happily Cottage Economy: To Which Is Added The Poor Man’s Friend is in the public domain, and you can read the whole thing at the Gutenberg Project, along with other books and pamphlets by Cobbett. But below are the two chapters on brewing beer.

21. These things will be altered. They must be altered. The nation must be sunk into nothingness, or a new system must be adopted; and the nation will not sink into nothingness. The malt now pays a tax of 4s. 6d.[1] a bushel, and the barley costs only 3s. This brings the bushel of malt to 8s. including the maltster’s charge for malting. If the tax were taken off the malt, malt would be sold, at the present price of barley, for about 3s. 3d. a bushel; because a bushel of barley makes more than a bushel of malt, and the tax, besides its amount, causes great expenses of various sorts to the maltster. The hops pay a tax of 2d.[2] a pound; and a bushel of malt requires, in general, a pound of hops; if these two taxes were taken off, therefore, the consumption of barley and of hops would be exceedingly increased; for double the present quantity would be demanded, and the land is always ready to send it forth.

22. It appears impossible that the landlords should much longer submit to these intolerable burdens on their estates. In short, they must get off the malt tax, or lose those estates. They must do a great deal more, indeed; but that they must do at any rate. The paper-money is fast losing its destructive power; and things are, with regard to the labourers, coming back to what they were forty years ago, and therefore we may prepare for the making of beer in our own houses, and take leave of the poisonous stuff served out to us by common brewers. We may begin immediately; for, even at present prices, home-brewed beer is the cheapest drink that a family can use, except milk, and milk can be applicable only in certain cases.

23. The drink which has come to supply the place of beer has, in general, been tea. It is notorious that tea has no useful strength in it; that it contains nothing nutritious; that it, besides being good for nothing, has badness in it, because it is well known to produce want of sleep in many cases, and in all cases, to shake and weaken the nerves. It is, in fact, a weaker kind of laudanum, which enlivens for the moment and deadens afterwards. At any rate it communicates no strength to the body; it does not, in any degree, assist in affording what labour demands. It is, then, of no use. And, now, as to its cost, compared with that of beer. I shall make my comparison applicable to a year, or three hundred and sixty-five days. I shall suppose the tea to be only five shillings the pound; the sugar only sevenpence; the milk only twopence a quart. The prices are at the very lowest. I shall suppose a tea-pot to cost a shilling, six cups and saucers two shillings and sixpence, and six pewter spoons eighteen-pence. How to estimate the firing I hardly know; but certainly there must be in the course of the year, two hundred fires made that would not be made, were it not for tea drinking. Then comes the great article of all, the time employed in this tea-making affair. It is impossible to make a fire, boil water, make the tea, drink it, wash up the things, sweep up the fire-place, and put all to rights again, in a less space of time, upon an average, than two hours. However, let us allow one hour; and here we have a woman occupied no less than three hundred and sixty-five hours in the year, or thirty whole days, at twelve hours in the day; that is to say, one month out of the twelve in the year, besides the waste of the man’s time in hanging about waiting for the tea! Needs there any thing more to make us cease to wonder at seeing labourers’ children with dirty linen and holes in the heels of their stockings? Observe, too, that the time thus spent is, one half of it, the best time of the day. It is the top of the morning, which, in every calling of life, contains an hour worth two or three hours of the afternoon. By the time that the clattering tea tackle is out of the way, the morning is spoiled; its prime is gone; and any work that is to be done afterwards lags heavily along. If the mother have to go out to work, the tea affair must all first be over. She comes into the field, in summer time, when the sun has gone a third part of his course. She has the heat of the day to encounter, instead of having her work done and being ready to return home at any early hour. Yet early she must go, too: for, there is the fire again to be made, the clattering tea-tackle again to come forward; and even in the longest day she must have candle light, which never ought to be seen in a cottage (except in case of illness) from March to September.

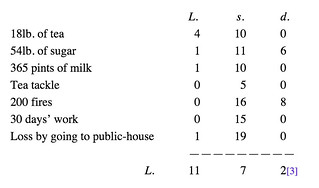

24. Now, then, let us take the bare cost of the use of tea. I suppose a pound of tea to last twenty days; which is not nearly half an ounce every morning and evening. I allow for each mess half a pint of milk. And I allow three pounds of the red dirty sugar to each pound of tea. The account of expenditure would then stand very high; but to these must be added the amount of the tea tackle, one set of which will, upon an average, be demolished every year. To these outgoings must be added the cost of beer at the public-house; for some the man will have, after all, and the woman too, unless they be upon the point of actual starvation. Two pots a week is as little as will serve in this way; and here is a dead loss of ninepence a week, seeing that two pots of beer, full as strong, and a great deal better, can be brewed at home for threepence. The account of the year’s tea drinking will then stand thus:

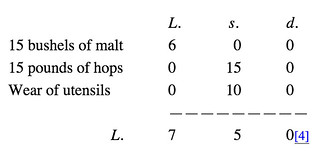

26. Well, then, to brew this ample supply of good beer for a labourer’s family, these 274 gallons, requires fifteen bushels of malt and (for let us do the thing well) fifteen pounds of hops. The malt is now eight shillings a bushel, and very good hops may be bought for less than a shilling a pound. The grains and yeast will amply pay for the labour and fuel employed in the brewing; seeing that there will be pigs to eat the grains, and bread to be baked with the yeast. The account will then stand thus:

28. It is not, however, the mere saving to which I look. This is, indeed, a matter of great importance, whether we look at the amount itself, or at the ultimate consequences of a judicious application of it; for four pounds make a great hole in a man’s wages for the year; and when we consider all the advantages that would arise to a family of children from having these four pounds, now so miserably wasted, laid out upon their backs, in the shape of a decent dress, it is impossible to look at this waste without feelings of sorrow not wholly unmixed with those of a harsher description.

29. But, I look upon the thing in a still more serious light. I view the tea drinking as a destroyer of health, an enfeebler of the frame, an engenderer of effeminacy and laziness, a debaucher of youth, and a maker of misery for old age. In the fifteen bushels of malt there are 570 pounds weight of sweet; that is to say, of nutricious matter, unmixed with any thing injurious to health. In the 730 tea messes of the year there are 54 pounds of sweet in the sugar, and about 30 pounds of matter equal to sugar in the milk. Here are 84 pounds instead of 570, and even the good effect of these 84 pounds is more than over-balanced by the corrosive, gnawing and poisonous powers of the tea.

30. It is impossible for any one to deny the truth of this statement. Put it to the test with a lean hog: give him the fifteen bushels of malt, and he will repay you in ten score of bacon or thereabouts. But give him the 730 tea messes, or rather begin to give them to him, and give him nothing else, and he is dead with hunger, and bequeaths you his skeleton, at the end of about seven days. It is impossible to doubt in such a case. The tea drinking has done a great deal in bringing this nation into the state of misery in which it now is; and the tea drinking, which is carried on by “dribs” and “drabs;” by pence and farthings going out at a time; this miserable practice has been gradually introduced by the growing weight of the taxes on malt and on hops, and by the everlasting penury amongst the labourers, occasioned by the paper-money.

31. We see better prospects however, and therefore let us now rouse ourselves, and shake from us the degrading curse, the effects of which have been much more extensive and infinitely more mischievous than men in general seem to imagine.

32. It must be evident to every one, that the practice of tea drinking must render the frame feeble and unfit to encounter hard labour or severe weather, while, as I have shown, it deducts from the means of replenishing the belly and covering the back. Hence succeeds a softness, an effeminacy, a seeking for the fire-side, a lurking in the bed, and, in short, all the characteristics of idleness, for which, in this case, real want of strength furnishes an apology. The tea drinking fills the public-house, makes the frequenting of it habitual, corrupts boys as soon as they are able to move from home, and does little less for the girls, to whom the gossip of the tea-table is no bad preparatory school for the brothel. At the very least, it teaches them idleness. The everlasting dawdling about with the slops of the tea tackle, gives them a relish for nothing that requires strength and activity. When they go from home, they know how to do nothing that is useful. To brew, to bake, to make butter, to milk, to rear poultry; to do any earthly thing of use they are wholly unqualified. To shut poor young creatures up in manufactories is bad enough; but there, at any rate, they do something that is useful; whereas, the girl that has been brought up merely to boil the tea-kettle, and to assist in the gossip inseparable from the practice, is a mere consumer of food, a pest to her employer, and a curse to her husband, if any man be so unfortunate as to fix his affections upon her.

33. But is it in the power of any man, any good labourer, who has attained the age of fifty, to look back upon the last thirty years of his life, without cursing the day in which tea was introduced into England? Where is there such a man, who cannot trace to this cause a very considerable part of all the mortifications and sufferings of his life? When was he ever too late at his labour; when did he ever meet with a frown, with a turning off, and pauperism on that account, without being able to trace it to the tea-kettle? When reproached with lagging in the morning, the poor wretch tells you that he will make up for it by working during his breakfast time! I have heard this a hundred and a hundred times over. He was up time enough; but the tea-kettle kept him lolling and lounging at home; and now, instead of sitting down to a breakfast upon bread, bacon, and beer, which is to carry him on to the hour of dinner, he has to force his limbs along under the sweat of feebleness, and at dinner time to swallow his dry bread, or slake his half-feverish thirst at the pump or the brook. To the wretched tea-kettle he has to return at night, with legs hardly sufficient to maintain him; and thus he makes his miserable progress towards that death, which he finds ten or fifteen years sooner than he would have found it had he made his wife brew beer instead of making tea. If he now and then gladdens his heart with the drugs of the public house, some quarrel, some accident, some illness, is the probable consequence; to the affray abroad succeeds an affray at home; the mischievous example reaches the children, corrupts them or scatters them, and misery for life is the consequence.

34. I should now proceed to the details of brewing; but these, though they will not occupy a large space, must be put off to the second number. The custom of brewing at home has so long ceased amongst labourers, and, in many cases, amongst tradesmen, that it was necessary for me fully to state my reasons for wishing to see the custom revived. I shall, in my next, clearly explain how the operation is performed; and it will be found to be so easy a thing, that I am not without hope, that many tradesmen, who now spend their evenings at the public house, amidst tobacco smoke and empty noise, may be induced, by the finding of better drink at home, at a quarter part of the price, to perceive that home is by far the pleasantest place wherein to pass their hours of relaxation.

35. My work is intended chiefly for the benefit of cottagers, who must, of course, have some land; for, I purpose to show, that a large part of the food of even a large family may be raised, without any diminution of the labourer’s earnings abroad, from forty rod, or a quarter of an acre, of ground; but at the same time, what I have to say will be applicable to larger establishments, in all the branches of domestic economy: and especially to that of providing a family with beer.

36. The kind of beer, for a labourer’s family, that is to say, the degree of strength, must depend on circumstances; on the numerousness of the family; on the season of the year, and various other things. But, generally speaking, beer half the strength of that mentioned in paragraph 25 will be quite strong enough; for that is, at least, one-third stronger than the farm-house “small beer,” which, however, as long experience has proved, is best suited to the purpose. A judicious labourer would probably always have some ale in his house, and have small beer for the general drink. There is no reason why he should not keep Christmas as well as the farmer; and when he is mowing, reaping, or is at any other hard work, a quart, or three pints, of really good fat ale a-day is by no means too much. However, circumstances vary so much with different labourers, that as to the sort of beer, and the number of brewings, and the times of brewing, no general rule can be laid down.

37. Before I proceed to explain the uses of the several brewing utensils, I must speak of the quality of the materials of which beer is made; that is to say, the malt, hops, and water. Malt varies very much in quality, as, indeed, it must, with the quality of the barley. When good, it is full of flour, and in biting a grain asunder, you find it bite easily, and see the shell thin and filled up well with flour. If it bite hard and steely, the malt is bad. There is pale malt and brown malt; but the difference in the two arises merely from the different degrees of heat employed in the drying. The main thing to attend to is, the quantity of flour. If the barley was bad; thin, or steely, whether from unripeness or blight, or any other cause, it will not malt so well; that is to say, it will not send out its roots in due time; and a part of it will still be barley. Then, the world is wicked enough to think, and even to say, that there are maltsters who, when they send you a bushel of malt, put a little barley amongst it, the malt being taxed and the barley not! Let us hope that this is seldom the case; yet, when we do know that this terrible system of taxation induces the beer-selling gentry to supply their customers with stuff little better than poison, it is not very uncharitable to suppose it possible for some maltsters to yield to the temptations of the devil so far as to play the trick above mentioned. To detect this trick, and to discover what portion of the barley is in an unmalted state, take a handful of the unground malt, and put it into a bowl of cold water. Mix it about with the water a little; that is, let every grain be just wet all over; and whatever part of them sink are not good. If you have your malt ground, there is not, as I know of, any means of detection. Therefore, if your brewing be considerable in amount, grind your own malt, the means of doing which is very easy, and neither expensive nor troublesome, as will appear, when I come to speak of flour. If the barley be well malted, there is still a variety in the quality of the malt; that is to say, a bushel of malt from fine, plump, heavy barley, will be better than the same quantity from thin and light barley. In this case, as in the case of wheat, the weight is the criterion of the quality. Only bear in mind, that as a bushel of wheat, weighing sixty-two pounds, is better worth six shillings, than a bushel weighing fifty-two is worth four shillings, so a bushel of malt weighing forty-five pounds is better worth nine shillings, than a bushel weighing thirty-five is worth six shillings. In malt, therefore, as in every thing else, the word cheap is a deception, unless the quality be taken into view. But, bear in mind, that in the case of unmalted barley, mixed with the malt, the weight can be no rule; for barley is heavier than malt.

39. With regard to hops, the quality is very various. At times when some sell for 5s. a pound, others sell for sixpence. Provided the purchaser understand the article, the quality is, of course, in proportion to the price. There are two things to be considered in hops: the power of preserving beer, and that of giving it a pleasant flavour. Hops may be strong; and yet not good. They should be bright, have no leaves or bits of branches amongst them. The hop is the husk, or seed-pod, of the hop-vine, as the cone is that of the fir-tree; and the seeds themselves are deposited, like those of the fir, round a little soft stalk, enveloped by the several folds of this pod, or cone. If, in the gathering, leaves of the vine or bits of the branches are mixed with the hops, these not only help to make up the weight, but they give a bad taste to the beer; and indeed, if they abound much, they spoil the beer. Great attention is therefore necessary in this respect. There are, too, numerous sorts of hops, varying in size, form, and quality, quite as much as apples. However, when they are in a state to be used in brewing, the marks of goodness are an absence of brown colour, (for that indicates perished hops;) a colour between green and yellow; a great quantity of the yellow farina; seeds not too large nor too hard; a clammy feel when rubbed between the fingers; and a lively, pleasant smell. As to the age of hops, they retain for twenty years, probably, their power of preserving beer; but not of giving it a pleasant flavour. I have used them at ten years old, and should have no fear of using them at twenty. They lose none of their bitterness; none of their power of preserving beer; but they lose the other quality; and therefore, in the making of fine ale, or beer, new hops are to be preferred. As to the quantity of hops, it is clear, from what has been said, that that must, in some degree depend upon their quality; but, supposing them to be good in quality, a pound of hops to a bushel of malt is about the quantity. A good deal, however, depends upon the length of time that the beer is intended to be kept, and upon the season of the year in which it is brewed. Beer intended to be kept a long while should have the full pound, also beer brewed in warmer weather, though for present use: half the quantity may do under an opposite state of circumstances.

40. The water should be soft by all means. That of brooks, or rivers, is best. That of a pond, fed by a rivulet, or spring, will do very well. Rain-water, if just fallen, may do; but stale rain-water, or stagnant pond-water, makes the beer flat and difficult to keep; and hard water, from wells, is very bad; it does not get the sweetness out of the malt, nor the bitterness out of the hops, like soft water; and the wort of it does not ferment well, which is a certain proof of its unfitness for the purpose.

41. There are two descriptions of persons whom I am desirous to see brewing their own beer; namely, tradesmen, and labourers and journeymen. There must, therefore, be two distinct scales treated of. In the former editions of this work, I spoke of a machine for brewing, and stated the advantages of using it in a family of any considerable consumption of beer; but, while, from my desire to promote private brewing, I strongly recommended the machine, I stated that, “if any of my readers could point out any method by which we should be more likely to restore the practice of private brewing, and especially to the cottage, I should be greatly obliged to them to communicate it to me.” Such communications have been made, and I am very happy to be able, in this new edition of my little work, to avail myself of them. There was, in the Patent Machine, always, an objection on account of the expense; for, even the machine for one bushel of malt cost, at the reduced price, eight pounds; a sum far above the reach of a cottager, and even above that of a small tradesman. Its convenience, especially in towns, where room is so valuable, was an object of great importance; but there were disadvantages attending it which, until after some experience, I did not ascertain. It will be remembered that the method by the brewing machine requires the malt to be put into the cold water, and for the water to make the malt swim, or, at least, to be in such proportion as to prevent the fire beneath from burning the malt. We found that our beer was flat, and that it did not keep. And this arose, I have every reason to believe, from this process. The malt should be put into hot water, and the water, at first, should be but just sufficient in quantity to stir the malt in, and separate it well. Nevertheless, when it is merely to make small beer; beer not wanted to keep; in such cases the brewing machine may be of use; and, as will be seen by-and-by, a moveable boiler (which has nothing to do with the patent) may, in many cases, be of great convenience and utility.

42. The two scales of which I have spoken above, are now to be spoken of; and, that I may explain my meaning the more clearly, I shall suppose, that, for the tradesman’s family, it will be requisite to brew eighteen gallons of ale and thirty-six of small beer, to fill three casks of eighteen gallons each. It will be observed, of course, that, for larger quantities, larger utensils of all sorts will be wanted. I take this quantity as the one to give directions on. The utensils wanted here will be, First, a copper that will contain forty gallons, at least; for, though there be to be but thirty-six gallons of small beer, there must be space for the hops, and for the liquor that goes off in steam. Second, a mashing-tub to contain sixty gallons; for the malt is to be in this along with the water. Third, an underbuck, or shallow tub to go under the mash-tub, for the wort to run into when drawn from the grains. Fourth, a tun-tub, that will contain thirty gallons, to put the ale into to work, the mash-tub, as we shall see, serving as a tun-tub for the small beer. Besides these, a couple of coolers, shallow tubs, which may be the heads of wine buts, or some such things, about a foot deep; or if you have four it may be as well, in order to effect the cooling more quickly.

43. You begin by filling the copper with water, and next by making the water boil. You then put into the mashing-tub water sufficient to stir and separate the malt in. But now let me say more particularly what this mashing-tub is. It is, you know, to contain sixty gallons. It is to be a little broader at top than at bottom, and not quite so deep as it is wide across the bottom. Into the middle of the bottom there is a hole about two inches over, to draw the wort off through. In this hole goes a stick, a foot or two longer than the tub is high. This stick is to be about two inches through, and tapered for about eight inches upwards at the end that goes into the hole, which at last it fills up closely as a cork. Upon the hole, before any thing else be put into the tub, you lay a little bundle of fine birch, (heath or straw may do,) about half the bulk of a birch broom, and well tied at both ends. This being laid over the hole (to keep back the grains as the wort goes out,) you put the tapered end of the stick down through into the hole, and thus cork the hole up. You must then have something of weight sufficient to keep the birch steady at the bottom of the tub, with a hole through it to slip down the stick; otherwise when the stick is raised it will be apt to raise the birch with it, and when you are stirring the mash you would move it from its place. The best thing for this purpose will be a leaden collar for the stick, with the hole in the collar plenty large enough, and it should weigh three or four pounds. The thing they use in some farm-houses is the iron box of a wheel. Any thing will do that will slide down the stick, and lie with weight enough on the birch to keep it from moving. Now, then, you are ready to begin brewing. I allow two bushels of malt for the brewing I have supposed. You must now put into the mashing-tub as much boiling water as will be sufficient to stir the malt in and separate it well. But here occur some of the nicest points of all; namely, the degree of heat that the water is to be at, before you put in the malt. This heat is one hundred and seventy degrees by the thermometer. If you have a thermometer, this is ascertained easily; but, without one, take this rule, by which so much good beer has been made in England for hundreds of years: when you can, by looking down into the tub, see your face clearly in the water, the water is become cool enough; and you must not put the malt in before. Now put in the malt and stir it well in the water. To perform this stirring, which is very necessary, you have a stick, somewhat bigger than a broom-stick, with two or three smaller sticks, eight or ten inches long, put through the lower end of it at about three or four inches asunder, and sticking out on each side of the long stick. These small cross sticks serve to search the malt and separate it well in the stirring or mashing. Thus, then, the malt is in; and in this state it should continue for about a quarter of an hour. In the mean while you will have filled up your copper, and made it boil; and now (at the end of the quarter of an hour) you put in boiling water sufficient to give you your eighteen gallons of ale. But, perhaps, you must have thirty gallons of water in the whole; for the grains will retain at least ten gallons of water; and it is better to have rather too much wort than too little. When your proper quantity of water is in, stir the malt again well. Cover the mashing-tub over with sacks, or something that will answer the same purpose; and there let the mash stand for two hours. When it has stood the two hours, you draw off the wort. And now, mind, the mashing-tub is placed on a couple of stools, or on something, that will enable you to put the underbuck under it, so as to receive the wort as it comes out of the hole before-mentioned. When you have put the underbuck in its place, you let out the wort by pulling up the stick that corks the whole. But, observe, this stick (which goes six or eight inches through the hole) must be raised by degrees, and the wort must be let out slowly, in order to keep back the sediment. So that it is necessary to have something to keep the stick up at the point where you are to raise it, and wish to fix it at for the time. To do this, the simplest, cheapest and best thing in the world is a cleft stick. Take a rod of ash, hazel, birch, or almost any wood; let it be a foot or two longer than your mashing-tub is wide over the top; split it, as if for making hoops; tie it round with a string at each end; lay it across your mashing-tub; pull it open in the middle, and let the upper part of the wort-stick through it, and when you raise that stick, by degrees as before directed, the cleft stick will hold it up at whatever height you please.

44. When you have drawn off the ale-wort, you proceed to put into the mashing tub water for the small beer. But, I shall go on with my directions about the ale till I have got it into the cask and cellar; and shall then return to the small-beer.

45. As you draw off the ale-wort into the underbuck, you must lade it out of that into the tun-tub, for which work, as well as for various other purposes in the brewing, you must have a bowl-dish with a handle to it. The underbuck will not hold the whole of the wort. It is, as before described, a shallow tub, to go under the mashing-tub to draw off the wort into. Out of this underbuck you must lade the ale-wort into the tun-tub; and there it must remain till your copper be emptied and ready to receive it.

46. The copper being empty, you put the wort into it, and put in after the wort, or before it, a pound and a half of good hops, well rubbed and separated as you put them in. You now make the copper boil, and keep it, with the lid off, at a good brisk boil, for a full hour, and if it be an hour and a half it is none the worse.

47. When the boiling is done, put out your fire, and put the liquor into the coolers. But it must be put into the coolers without the hops. Therefore, in order to get the hops out of the liquor, you must have a strainer. The best for your purpose is a small clothes-basket, or any other wicker-basket. You set your coolers in the most convenient place. It may be in-doors or out of doors, as most convenient. You lay a couple of sticks across one of the coolers, and put the basket upon them. Put your liquor, hops and all, into the basket, which will keep back the hops. When you have got liquor enough in one cooler, you go to another with your sticks and basket, till you have got all your liquor out. If you find your liquor deeper in one cooler than the other, you can make an alteration in that respect, till you have the liquor so distributed as to cool equally fast in both, or all, the coolers.

48. The next stage of the liquor is in the tun-tub, where it is set to work. Now, a very great point is, the degree of heat that the liquor is to be at when it is set to working. The proper heat is seventy degrees; so that a thermometer makes this matter sure. In the country they determine the degree of heat by merely putting a finger into the liquor. Seventy degrees is but just warm, a gentle luke-warmth. Nothing like heat. A little experience makes perfectness in such a matter. When at the proper heat, or nearly, (for the liquor will cool a little in being removed,) put it into the tun-tub. And now, before I speak of the act of setting the beer to work, I must describe this tun-tub, which I first mentioned in Paragraph 42. It is to hold thirty gallons, as you have seen; and nothing is better than an old cask of that size, or somewhat larger, with the head taken out, or cut off. But, indeed, any tub of sufficient dimensions, and of about the same depth proportioned to the width as a cask or barrel has, will do for the purpose. Having put the liquor into the tun-tub, you put in the yeast. About half a pint of good yeast is sufficient. This should first be put into a thing of some sort that will hold about a gallon of your liquor; the thing should then be nearly filled with liquor, and with a stick or spoon you should mix the yeast well with the liquor in this bowl, or other thing, and stir in along with the yeast a handful of wheat or rye flour. This mixture is then to be poured out clean into the tun-tub, and the whole mass of the liquor is then to be agitated well by lading up and pouring down again with your bowl-dish, till the yeast be well mixed with the liquor. Some people do the thing in another manner. They mix up the yeast and flour with some liquor (as just mentioned) taken out of the coolers; and then they set the little vessel that contains this mixture down on the bottom of the tun-tub; and, leaving it there, put the liquor out of the coolers into the tun-tub. Being placed at the bottom, and having the liquor poured on it, the mixture is, perhaps, more perfectly effected in this way than in any way. The flour may not be necessary; but, as the country people use it, it is, doubtless, of some use; for their hereditary experience has not been for nothing. When your liquor is thus properly put into the tun-tub and set a working, cover over the top of the tub by laying across it a sack or two, or something that will answer the purpose.

49. We now come to the last stage; the cask or barrel. But I must first speak of the place for the tun-tub to stand in. The place should be such as to avoid too much warmth or cold. The air should, if possible, be at about 55 degrees. Any cool place in summer and any warmish place in winter. If the weather be very cold, some cloths or sacks should be put round the tun-tub while the beer is working. In about six or eight hours, a frothy head will rise upon the liquor; and it will keep rising, more or less slowly, for about forty-eight hours. But, the length of time required for the working depends on various circumstances; so that no precise time can be fixed. The best way is, to take off the froth (which is indeed yeast) at the end of about twenty-four hours, with a common skimmer, and put it into a pan or vessel of some sort; then, in twelve hours’ time, take it off again in the same way; and so on till the liquor has done working, and sends up no more yeast. Then it is beer; and when it is quite cold (for ale or strong beer) put it into the cask by means of a funnel. It must be cold before you do this, or it will be what the country-people call foxed; that is to say, have a rank and disagreeable taste. Now, as to the cask, it must be sound and sweet. I thought, when writing the former edition of this work, that the bell-shaped were the best casks. I am now convinced that that was an error. The bell-shaped, by contracting the width of the top of the beer, as that top descends, in consequence of the draft for use, certainly prevents the head (which always gathers on beer as soon as you begin to draw it off) from breaking and mixing in amongst the beer. This is an advantage in the bell-shape; but then the bell-shape, which places the widest end of the cask uppermost, exposes the cask to the admission of external air much more than the other shape. This danger approaches from the ends of the cask; and, in the bell-shape, you have the broadest end wholly exposed the moment you have drawn out the first gallon of beer, which is not the case with the casks of the common shape. Directions are given, in the case of the bell-casks, to put damp sand on the top to keep out the air. But, it is very difficult to make this effectual; and yet, if you do not keep out the air, your beer will be flat; and when flat, it really is good for nothing but the pigs. It is very difficult to fill the bell-cask, which you will easily see if you consider its shape. It must be placed on the level with the greatest possible truth, or there will be a space left; and to place it with such truth is, perhaps, as difficult a thing as a mason or bricklayer ever had to perform. And yet, if this be not done, there will be an empty space in the cask, though it may, at the same time, run over. With the common casks there are none of these difficulties. A common eye will see when it is well placed; and, at any rate, any little vacant space that may be left is not at an end of the cask, and will, without great carelessness, be so small as to be of no consequence. We now come to the act of putting in the beer. The cask should be placed on a stand with legs about a foot long. The cask, being round, must have a little wedge, or block, on each side to keep it steady. Bricks do very well. Bring your beer down into the cellar in buckets, and pour it in through the funnel, until the cask be full. The cask should lean a little on one side, when you fill it; because the beer will work again here, and send more yeast out of the bung-hole; and, if the cask were not a little on one side, the yeast would flow over both sides of the cask, and would not descend in one stream into a pan, put underneath to receive it. Here the bell-cask is extremely inconvenient; for the yeast works up all over the head, and cannot run off, and makes a very nasty affair. This alone, to say nothing of the other disadvantages, would decide the question against the bell-casks. Something will go off in this working, which may continue for two or three days. When you put the beer in the cask, you should have a gallon or two left, to keep filling up with as the working produces emptiness. At last, when the working is completely over, right the cask. That is to say, block it up to its level. Put in a handful of fresh hops. Fill the cask quite full. Put in the bung, with a bit of coarse linen stuff round it; hammer it down tight; and, if you like, fill a coarse bag with sand, and lay it, well pressed down, over the bung.

50. As to the length of time that you are to keep the beer before you begin to use it, that must, in some measure, depend on taste. Such beer as this ale will keep almost any length of time. As to the mode of tapping, that is as easy almost as drinking. When the cask is empty, great care must be taken to cork it tightly up, so that no air get in; for, if it do, the cask is moulded, and when once moulded, it is spoiled for ever. It is never again fit to be used about beer. Before the cask be used again, the grounds must be poured out, and the cask cleaned by several times scalding; by putting in stones (or a chain,) and rolling and shaking about till it be quite clean. Here again the round casks have the decided advantage; it being almost impossible to make the bell-casks thoroughly clean, without taking the head out, which is both troublesome and expensive; as it cannot be well done by any one but a cooper, who is not always at hand, and who, when he is, must be paid.

51. I have now done with the ale, and it remains for me to speak of the small beer. In Paragraph 47 (which now see) I left you drawing off the ale-wort, and with your copper full of boiling water. Thirty-six gallons of that boiling water are, as soon as you have got your ale-wort out, and have put down your mash-tub stick to close up the hole at the bottom; as soon as you have done this, thirty-six gallons of the boiling water are to go into the mashing-tub; the grains are to be well stirred up, as before; the mashing-tub is to be covered over again, as mentioned in Paragraph 43; and the mash is to stand in that state for an hour, and not two hours, as for the ale-wort.

52. When the small beer mash has stood its hour, draw it off as in Paragraph 47, and put it into the tun-tub as you did the ale-wort.

53. By this time your copper will be empty again, by putting your ale-liquor to cool, as mentioned in Paragraph 47. And you now put the small beer wort into the copper, with the hops that you used before, and with half a pound of fresh hops added to them; and this liquor you boil briskly for an hour.

54. By this time you will have taken the grains and the sediment clean out of the mashing-tub, and taken out the bunch of birch twigs, and made all clean. Now put in the birch twigs again, and put down your stick as before. Lay your two or three sticks across the mashing-tub, put your basket on them, and take your liquor from the copper (putting the fire out first) and pour it into the mashing-tub through the basket. Take the basket away, throw the hops to the dunghill, and leave the small beer liquid to cool in the mashing-tub.

55. Here it is to remain to be set to working as mentioned for the ale, in Paragraph 48; only, in this case, you will want more yeast in proportion; and should have for your thirty-six gallons of small beer, three half pints of good yeast.

56. Proceed, as to all the rest of the business, as with the ale, only, in the case of the small beer, it should be put into the cask, not quite cold, but a little warm; or else it will not work at all in the barrel, which it ought to do. It will not work so strongly or so long as the ale; and may be put in the barrel much sooner; in general the next day after it is brewed.

57. All the utensils should be well cleaned and put away as soon as they are done with; the little things as well as the great things; for it is loss of time to make new ones. And, now, let us see the expense of these utensils. The copper, new, 5l.; the mashing-tub, new, 30s.; the tun-tub, not new, 5s.; the underbuck and three coolers, not new, 20s. The whole cost is 7l. 10s. which is ten shillings less than the one bushel machine. I am now in a farm-house, where the same set of utensils has been used for forty years; and the owner tells me, that, with the same use, they may last for forty years longer. The machine will not, I think, last four years, if in any thing like regular use. It is of sheet-iron, tinned on the inside, and this tin rusts exceedingly, and is not to be kept clean without such rubbing as must soon take off the tin. The great advantage of the machine is, that it can be removed. You can brew without a brew-house.—You can set the boiler up against any fire-place, or any window. You can brew under a cart-shed, and even out of doors. But all this may be done with these utensils, if your copper be moveable. Make the boiler of copper, and not of sheet-iron, and fix it on a stand with a fire-place and stove-pipe; and then you have the whole to brew out of doors with as well as in-doors, which is a very great convenience.

58. Now with regard to the other scale of brewing, little need be said; because, all the principles being the same, the utensils only are to be proportioned to the quantity. If only one sort of beer be to be brewed at a time, all the difference is, that, in order to extract the whole of the goodness of the malt, the mashing ought to be at twice. The two worts are then put together, and then you boil them together with the hops.

59. A Correspondent at Morpeth says, the whole of the utensils used by him are a twenty-gallon pot, a mashing-tub, that also answers for a tun-tub, and a shallow tub for a cooler; and that these are plenty for a person who is any thing of a contriver. This is very true; and these things will cost no more, perhaps, than forty shillings. A nine gallon cask of beer can be brewed very well with such utensils. Indeed, it is what used to be done by almost every labouring man in the kingdom, until the high price of malt and comparatively low price of wages rendered the people too poor and miserable to be able to brew at all. A Correspondent at Bristol has obligingly sent me the model of utensils for brewing on a small scale; but as they consist chiefly of brittle ware, I am of opinion that they would not so well answer the purpose.

60. Indeed, as to the country labourers, all they want is the ability to get the malt. Mr. Ellman, in his evidence before the Agricultural Committee, said, that, when he began farming, forty-five years ago, there was not a labourer’s family in the parish that did not brew their own beer and enjoy it by their own fire-sides; and that, now, not one single family did it, from want of ability to get the malt. It is the tax that prevents their getting the malt; for, the barley is cheap enough. The tax causes a monopoly in the hands of the maltsters, who, when the tax is two and sixpence, make the malt, cost 7s. 6d., though the barley cost but 2s. 6d.; and though the malt, tax and all, ought to cost him about 5s. 6d. If the tax were taken off, this pernicious monopoly would be destroyed.

61. The reader will easily see, that, in proportion to the quantity wanted to be brewed must be the size of the utensils; but, I may observe here, that the above utensils are sufficient for three, or even four, bushels of malt, if stronger beer be wanted.

62. When it is necessary, in case of falling short in the quantity wanted to fill up the ale cask, some may be taken from the small beer. But, upon the whole brewing, there ought to be no falling short; because, if the casks be not filled up, the beer will not be good, and certainly will not keep. Great care should be taken as to the cleansing of the casks. They should be made perfectly sweet; or it is impossible to have good beer.

63. The cellar, for beer to keep any length of time, should be cool. Under a hill is the best place for a cellar; but, at any rate, a cellar of good depth, and dry. At certain times of the year, beer that is kept long will ferment. The vent-pegs must, in such cases, be loosened a little, and afterwards fastened.

64. Small beer may be tapped almost directly. It is a sort of joke that it should see a Sunday; but, that it may do before it be two days old. In short, any beer is better than water; but it should have some strength and some weeks of age at any rate.

65. I cannot conclude this Essay without expressing my pleasure, that a law has been recently passed to authorize the general retail of beer. This really seems necessary to prevent the King’s subjects from being poisoned. The brewers and porter quacks have carried their tricks to such an extent, that there is no safety for those who drink brewer’s beer.

66. The best and most effectual thing is, however, for people to brew their own beer, to enable them and induce them to do which, I have done all that lies in my power. A longer treatise on the subject would have been of no use. These few plain directions will suffice for those who have a disposition to do the thing, and those who have not would remain unmoved by any thing that I could say.

67. There seems to be a great number of things to do in brewing, but the greater part of them require only about a minute each. A brewing, such as I have given the detail of above, may be completed in a day; but, by the word day, I mean to include the morning, beginning at four o’clock.

68. The putting of the beer into barrel is not more than an hour’s work for a servant woman, or a tradesman’s or a farmer’s wife. There is no heavy work, no work too heavy for a woman in any part of the business, otherwise I would not recommend it to be performed by the women, who, though so amiable in themselves, are never quite so amiable as when they are useful; and as to beauty, though men may fall in love with girls at play, there is nothing to make them stand to their love like seeing them at work. In conclusion of these remarks on beer brewing, I once more express my most anxious desire to see abolished for ever the accursed tax on malt, which, I verily believe, has done more harm to the people of England than was ever done to any people by plague, pestilence, famine, and civil war.

69. In Paragraph 76, in Paragraph 108, and perhaps in another place or two (of the last edition,) I spoke of the machine for brewing. The work being stereotyped, it would have been troublesome to alter those paragraphs; but, of course, the public, in reading them, will bear in mind what has been now said relative to the machine. The inventor of that machine deserves great praise for his efforts to promote private brewing; and, as I said before, in certain confined situations, and where the beer is to be merely small beer, and for immediate use, and where time and room are of such importance as to make the cost of the machine comparatively of trifling consideration, the machine may possibly be found to be an useful utensil.

70. Having stated the inducements to the brewing of beer, and given the plainest directions that I was able to give for the doing of the thing, I shall, next, proceed to the subject of bread. But this subject is too large and of too much moment to be treated with brevity, and must, therefore, be put off till my next Number. I cannot, in the mean while, dismiss the subject of brewing beer without once more adverting to its many advantages, as set forth in the foregoing Number of this work.

71. The following instructions for the making of porter, will clearly show what sort of stuff is sold at public-houses in London; and we may pretty fairly suppose that the public-house beer in the country is not superior to it in quality, “A quarter of malt, with these ingredients, will make five barrels of good porter. Take one quarter of high-coloured malt, eight pounds of hops, nine pounds of treacle, eight pounds of colour, eight pounds of sliced liquorice-root, two drams of salt of tartar, two ounces of Spanish-liquorice, and half an ounce of capsicum.” The author says, that he merely gives the ingredients, as used by many persons.

72. This extract is taken from a book on brewing, recently published in London. What a curious composition! What a mess of drugs! But, if the brewers openly avow this, what have we to expect from the secret practices of them, and the retailers of the article! When we know, that beer-doctor and brewers’-druggist are professions, practised as openly as those of bug-man and rat-killer, are we simple enough to suppose that the above-named are the only drugs that people swallow in those potions, which they call pots of beer? Indeed, we know the contrary; for scarcely a week passes without witnessing the detection of some greedy wretch, who has used, in making or in doctoring his beer, drugs, forbidden by the law. And, it is not many weeks since one of these was convicted, in the Court of Excise, for using potent and dangerous drugs, by the means of which, and a suitable quantity of water, he made two buts of beer into three. Upon this occasion, it appeared that no less than ninety of these worthies were in the habit of pursuing the same practices. The drugs are not unpleasant to the taste; they sting the palate: they give a present relish: they communicate a momentary exhilaration: but, they give no force to the body, which, on the contrary, they enfeeble, and, in many instances, with time, destroy; producing diseases from which the drinker would otherwise have been free to the end of his days.

73. But, look again at the receipt for making porter. Here are eight bushels of malt to 180 gallons of beer; that is to say, twenty-fire gallons from the bushel. Now the malt is eight shillings a bushel, and eight pounds of the very best hops will cost but a shilling a pound. The malt and hops, then, for the 180 gallons, cost but seventy-two shillings; that is to say, only a little more than fourpence three farthings a gallon, for stuff which is now retailed for sixteen pence a gallon! If this be not an abomination, I should be glad to know what is. Even if the treacle, colour, and the drugs, be included, the cost is not fivepence a gallon; and yet, not content with this enormous extortion, there are wretches who resort to the use of other and pernicious drugs, in order to increase their gains!

74. To provide against this dreadful evil there is, and there can be, no law; for, it is created by the law. The law it is that imposes the enormous tax on the malt and hops; the law it is that imposes the license tax, and places the power of granting the license at the discretion of persons appointed by the government; the law it is that checks, in this way, the private brewing, and that prevents free and fair competition in the selling of beer, and as long as the law does these, it will in vain endeavour to prevent the people from being destroyed by slow poison.

75. Innumerable are the benefits that would arise from a repeal of the taxes on malt and on hops. Tippling-houses might then be shut up with justice and propriety. The labourer, the artisan, the tradesman, the landlord, all would instantly feel the benefit. But the landlord more, perhaps, in this case, than any other member of the community. The four or five pounds a year which the day-labourer now drizzles away in tea-messes, he would divide with the farmer, if he had untaxed beer. His wages would fall, and fall to his advantage too. The fall of wages would be not less than 40l. upon a hundred acres. Thus 40l. would go, in the end, a fourth, perhaps to the farmer, and three-fourths to the landlord. This is the kind of work to reduce poor-rates, and to restore husbandry to prosperity. Undertaken this work must be, and performed too; but whether we shall see this until the estates have passed away from the present race of landlords, is a question which must be referred to time.

76. Surely we may hope, that, when the American farmers shall see this little Essay, they will begin seriously to think of leaving off the use of the liver-burning and palsy-producing spirits. Their climate, indeed, is something: extremely hot in one part of the year, and extremely cold in the other part of it. Nevertheless, they may have, and do have, very good beer if they will. Negligence is the greatest impediment in their way. I like the Americans very much; and that, if there were no other, would be a reason for my not hiding their faults.

- Section 23: tea has come to supply the place of beer; tea is a weaker kind of laudanum (opium); huge cost of tea; waste of time and of the best part of the day.

- Section 25: beer much cheaper than tea; suitable for all but the smallest children; up to five quarts a day enough for all but drunkards.

- Section 29: tea destroys health and causes effeminacy; tea has little of the nutritional value of beer.

- Section 30: undeniable proof: tea kills pigs.

- Section 32: tea leads men to idleness; and women to the brothel.

Given how synonymous tea is with British culture and identity, it’s fun to see that it wasn’t always the case. But in Cobbett’s lifetime, it was still a relatively new phenomenon, and apparently he really didn’t like change very much.