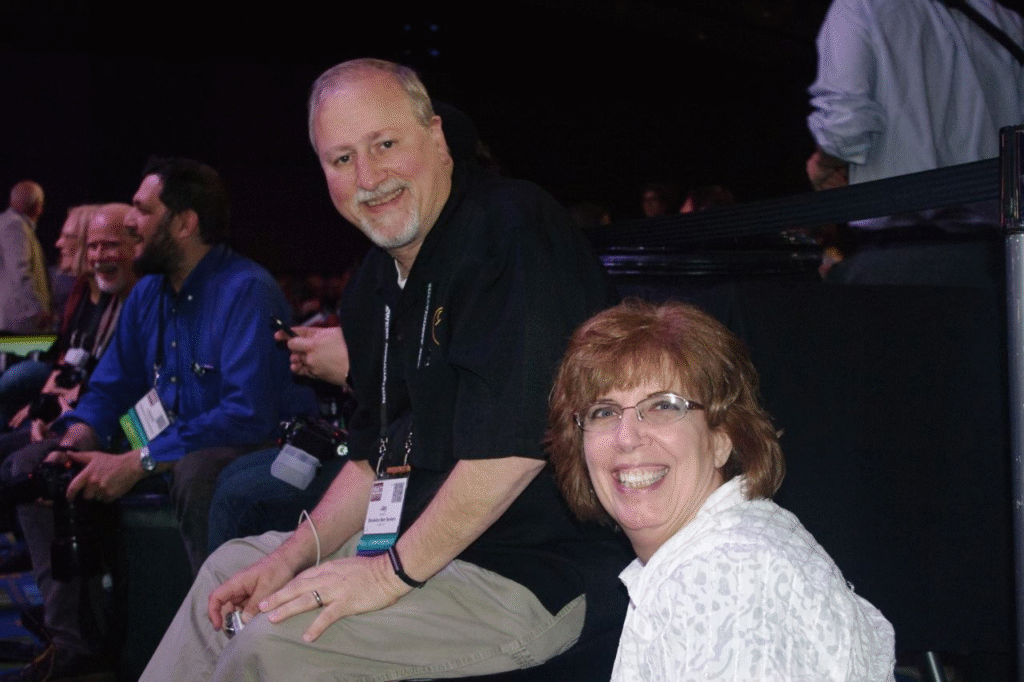

Today is Carolyn Smagalski’s birthday. Carolyn’s a beer writer from Pennsylvania — not sure what it is about Pennsylvania and beer writing — who writes for BellaOnline. Her nickname is the Beer Fox and she does a terrific job spreading the gospel of great beer. Join me in wishing Carolyn a very happy birthday.

NOTE: Previous three photos purloined from Facebook.