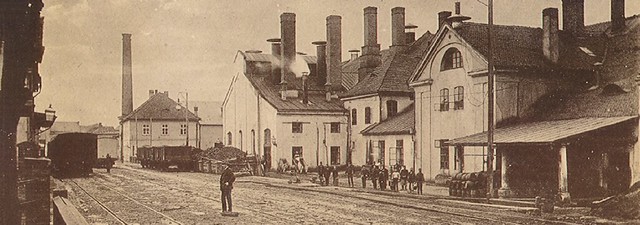

Today is the birthday of John Weidenfeller (February 11, 1867-1929). He was born in Germany, but came to America with his family, who settled in Michigan and owned a farm. Weidenfeller though, defying his father’s wishes, became a brewer, working first with “Frey Bros. and Kusterer Brewing Companies. In 1892, these two breweries joined three others to form the Grand Rapids Brewing Co.” He later worked in Montana for the Centennial Brewery, before accepting a position as brewmaster of Olympia Brewing in Washington.

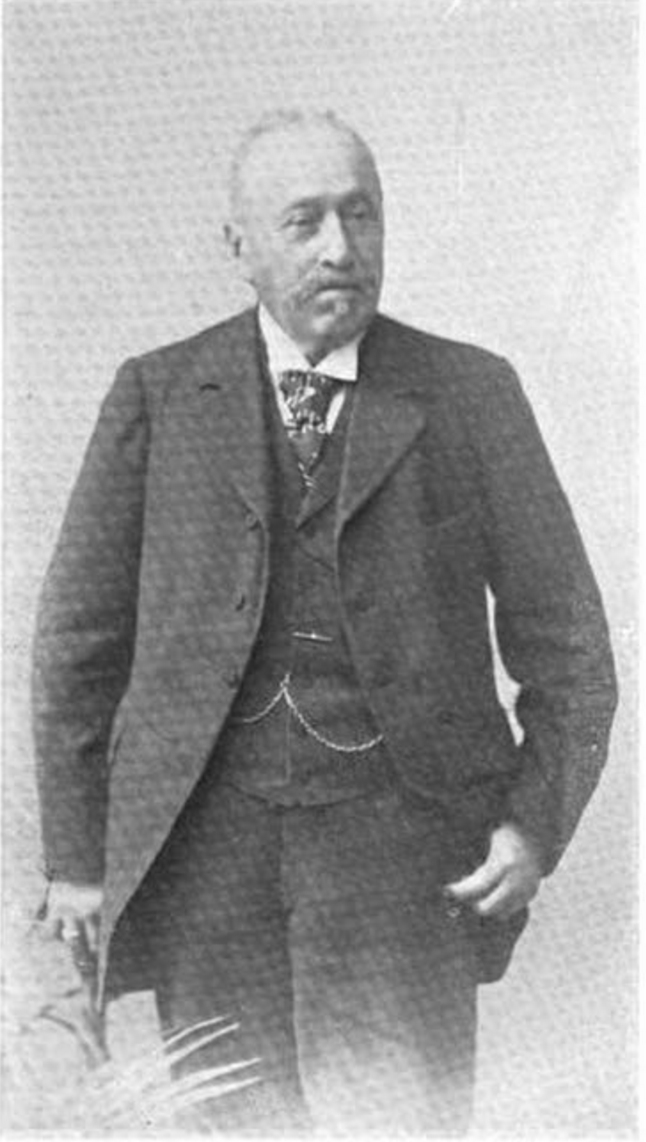

There’s also a photograph of Weidenfeller that can be seen at Brewery Gems’ biography of John Weidenfeller shared with him by the brewer’s family.

There’s less about brewmasters, as opposed to brewers who were also brewery founders or owners, when you go back this far, but there’s a pretty thorough biography of Weidenfeller by Gary Flynn at his website Brewery Gems.

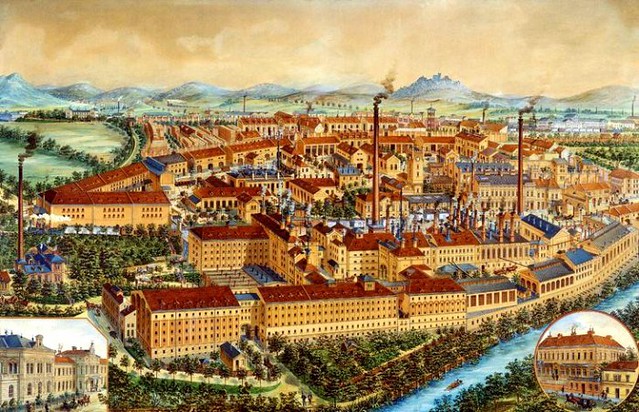

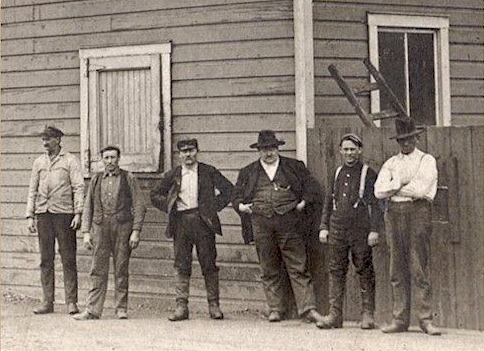

Weidenfeller around 1901, with his workers in Montana.