Today is the birthday of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll. He was “an English writer of world-famous children’s fiction, notably Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass. He was noted for his facility at word play, logic and fantasy. The poems Jabberwocky and The Hunting of the Snark are classified in the genre of literary nonsense. He was also a mathematician, photographer, and Anglican deacon.” One of his

In the latter, Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, Carroll writes about his idea on how to keep drunkards at home, drinking their beer there and not throwing away the family’s money, all to the betterment of society. It begins in Chapter V: Mathilda Jane.

When the full stream of loving memories had nearly run itself out, I began to question her about the working men of that

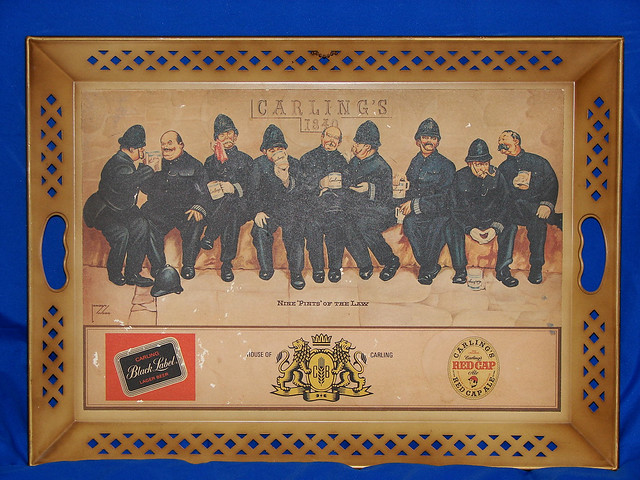

neighbourhood , andspecially the ‘Willie,’ whom we had heard of at his cottage. “He was a good fellow once,” said my kind hostess: “but it’s the drink has ruined him! Not that I’d rob them of the drink—it’s good for the most of them—but there’s some as is too weak to stand agin’ temptations: it’s a thousand pities, for them, as they ever built the Golden Lion at the corner there!”“The Golden Lion?” I repeated.

“It’s the new Public,” my hostess explained. “And it stands right in the way, and handy for the workmen, as they come back from the brickfields, as it might be

to-day , with their week’s wages. A deal of money gets wasted that way. And some of ’em gets drunk.”“If only they could have it in their own houses—” I mused, hardly knowing I had said the words out loud.

“That’s it!” she eagerly exclaimed. It was evidently a solution, of the problem, that she had already thought out. “If only you could manage, so’s each man to have his own little barrel in his own house—there’d hardly be a drunken man in the length and breadth of the land!”

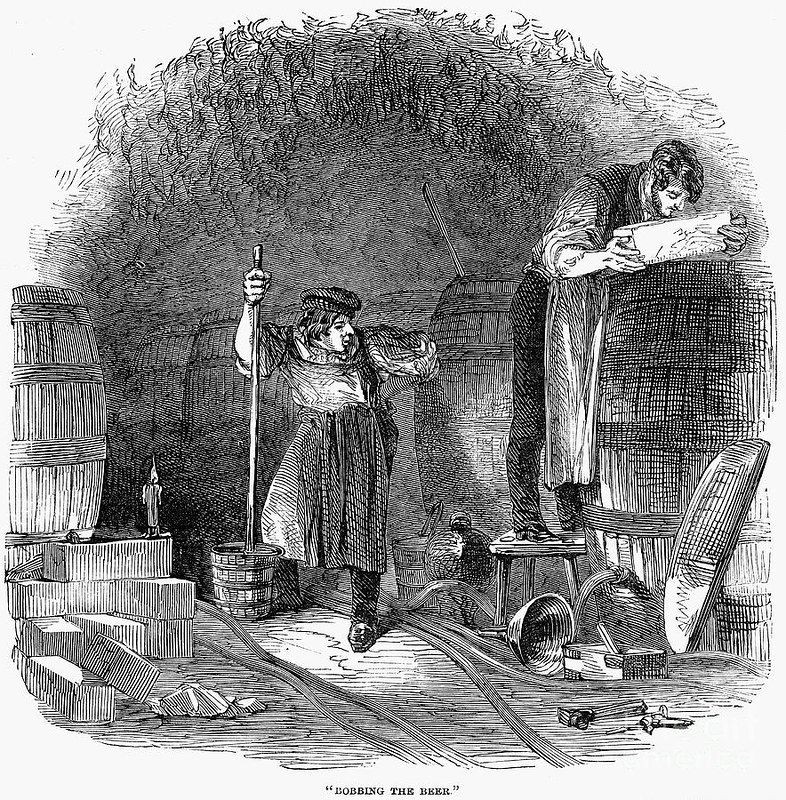

And then I told her the old story—about a certain cottager who bought himself a little barrel of beer, and installed his wife as bar-keeper: and how, every time he wanted his mug of beer, he regularly paid her over the counter for it: and how she never would let him go on ‘tick,’ and was a perfectly inflexible bar-keeper in never letting him have more than his proper allowance: and how, every time the barrel needed refilling, she had plenty to do it with, and something over for her money-box: and how, at the end of the year, he not only found himself in first-rate health and spirits, with that undefinable but quite unmistakeable air which always distinguishes the sober man from the one who takes ‘a drop too much,’ but had quite a box full of money, all saved out of his own pence!

“If only they’d all do like that!” said the good woman, wiping her eyes, which were overflowing with kindly sympathy. “Drink hadn’t need to be the curse it is to some——”

“Only a curse,” I said, “when it is used wrongly. Any of God’s gifts may be turned into a curse, unless we use it wisely. But we must be getting home. Would you call the little girls? Matilda Jane has seen enough of

company , for one day, I’m sure!”

So Carroll insists that it’s not beer or drink that’s bad for them, it’s over-indulging in it. That seems a rather progressive idea for 1893, especially in the face of temperance movements of the day.

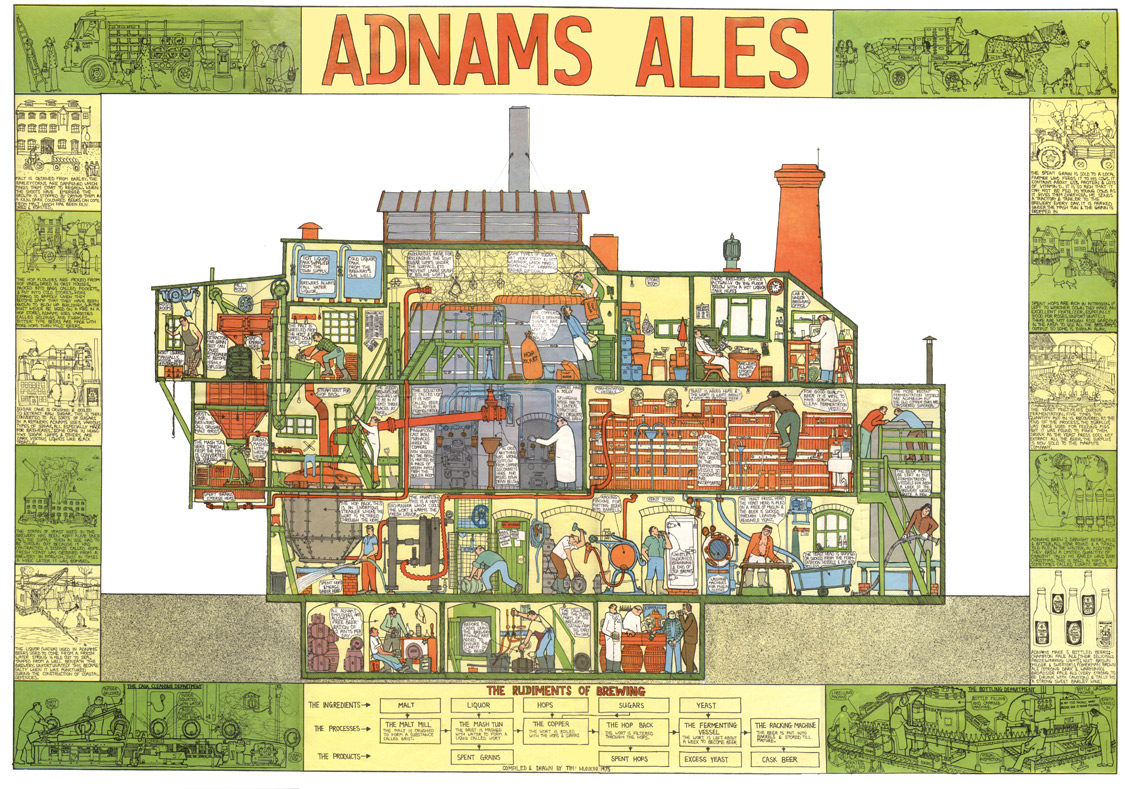

But his solution is sublime. To avoid so many people wasting their wages down at the pub, just give every household its own Kegerator and barrel of beer so they’ll instead come home most nights and drink their beer there with their family. Genius.

Later in the chapter, Sylvie and Bruno find themselves outside The Golden Lion.

“And that’s the new public-house that we were talking about, I suppose?” I

said, as we came in sight of a long low building, with the words ‘The Golden Lion’ over the door.“Yes, that’s it,” said Sylvie. “I wonder if her Willie’s inside? Run in, Bruno, and see if he’s there.”

I interposed, feeling that Bruno was, in a sort of way, in my care. “That’s not a place to send a child into.” For already the revelers were getting noisy: and a wild discord of singing, shouting, and meaningless laughter came to us through the open windows.

“They

wo’n’t see him, you know,” Sylvie explained. “Wait a minute, Bruno!” She clasped the jewel, that always hunground her neck, between the palms of her hands, and muttered a few words to herself. What they were I could not at all make out, but some mysterious change seemed instantly to pass over us. My feet seemed tome no longer to press the ground, and the dream-like feeling came upon me, that I was suddenly endowed with the power of floating in the air. I could still just see the children: but their forms were shadowy and unsubstantial, and their voices sounded as if they came from some distant place and time, they were so unreal. However, I offered no further opposition to Bruno’s going into the house. He was back again in a few moments. “No, he isn’t come yet,” he said. “They’re talking about him inside, and saying how drunk he was last week.”While he was speaking, one of the men lounged out through the door, a pipe in one hand and a mug of beer in the other, and crossed to where we were standing, so as to get a better view along the road. Two or three others leaned out through the open window, each holding his mug of beer, with red faces and sleepy eyes. “Canst see him, lad?” one of them asked.

“I

dunnot know,” the man said, taking a stepforwards , which brought us nearly face to face. Sylvie hastily pulled me out of his way. “Thanks, child,” I said. “I had forgotten he couldn’t see us. What would have happened if I had staid in his way?”

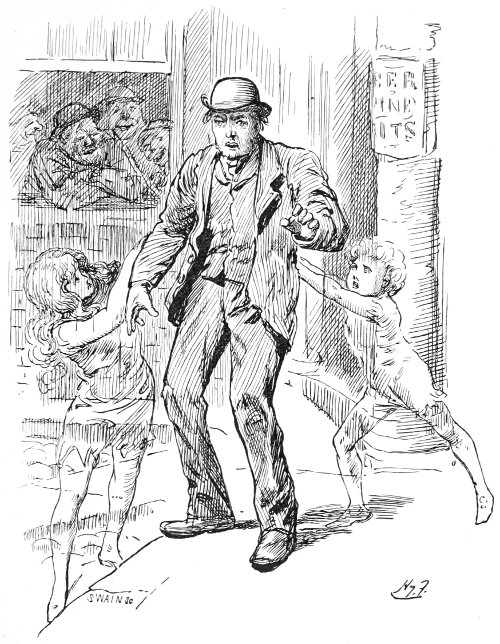

In Chapter VI, they decide to rescue Willie from his pub crawling ways.

He made for the door of the public-house, but the children intercepted him. Sylvie clung to one arm; while Bruno, on the opposite side, was pushing him with all his strength, with many inarticulate cries of “Gee-up! Gee-back! Woah then!” which he had picked up from the waggoners.

‘Willie’ took not the least notice of them: he was simply conscious that something had checked him: and, for want of any other way of accounting for it, he seemed to regard it as his own act.

“I wunnut coom in,” he said: “not to-day.”

“A mug o’ beer wunnut hurt ’ee!” his friends shouted in chorus. “Two mugs wunnut hurt ’ee! Nor a dozen mugs!”84

“Nay,” said Willie. “I’m agoan whoam.”

“What, withouten thy drink, Willie man?” shouted the others. But ‘Willie man’ would have no more discussion, and turned doggedly away, the children keeping one on each side of him, to guard him against any change in his sudden resolution.

Willie went home and gave all his wages to his wife, and she was pretty happy, as were his children. The only thing that would have made the ending better is if his wife had installed a barrel of beer so he could come home every day after work and have a drink of beer there, as was the earlier suggestion Carroll made.