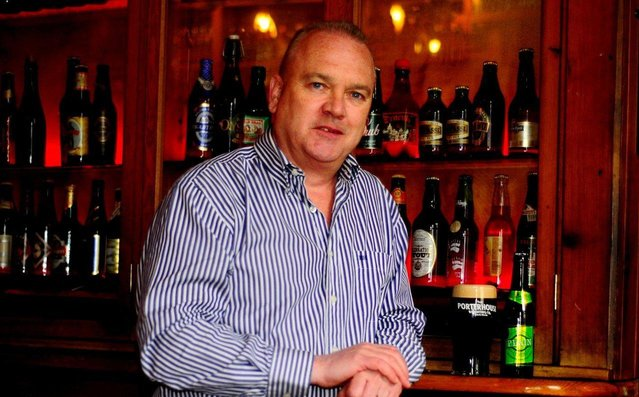

Today is the 39th birthday of Irish beer writer Eoghan Walsh, whose work brought him to live in Brussels, Belgium, where he writes the blog Brussels Beer City. While I was aware of Eoghan’s work thanks to the interwebs, I finally got to meet and spend some time with him during judging for the Brussels Beer Challenge a few years ago, which was great fun. Join me in wishing Eoghan a very happy birthday.