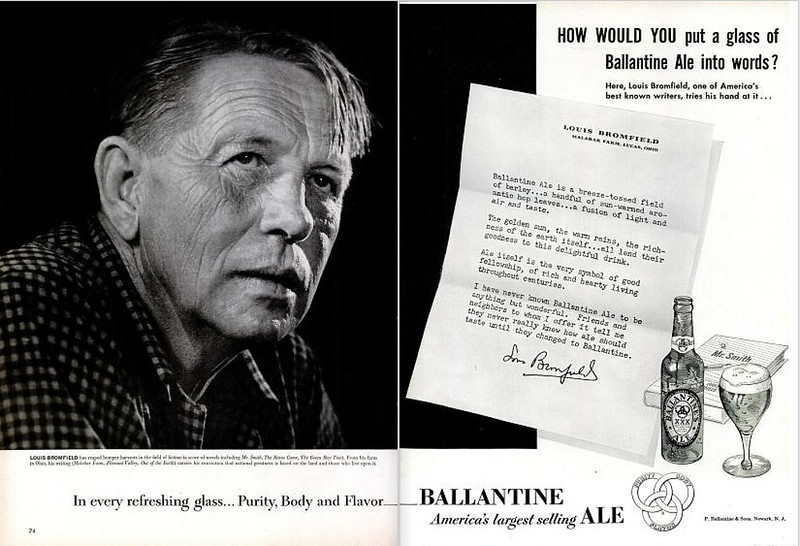

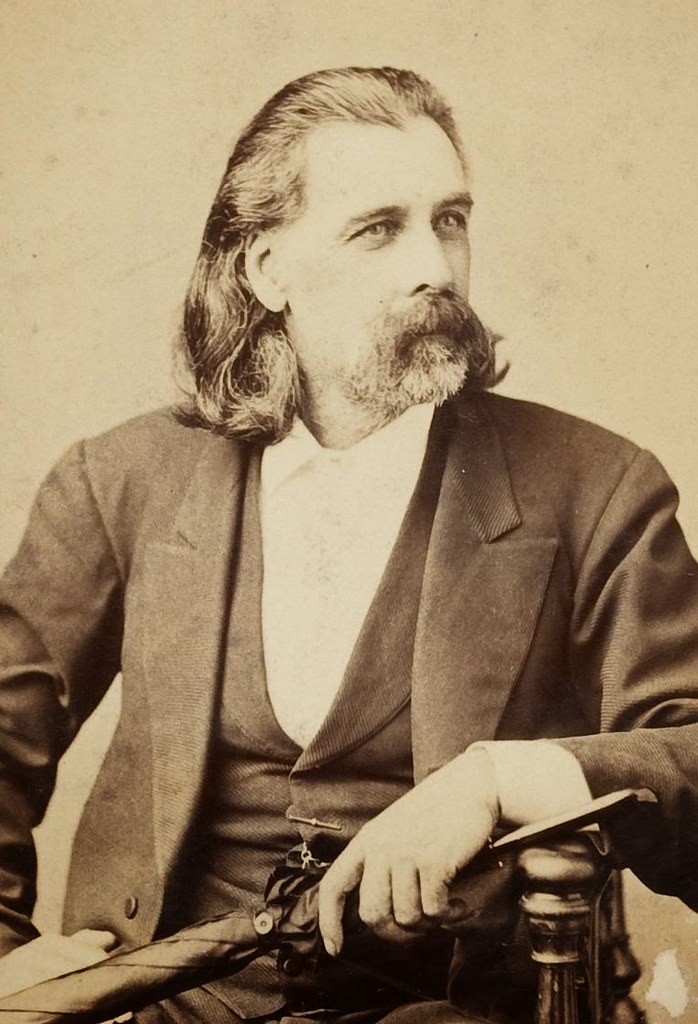

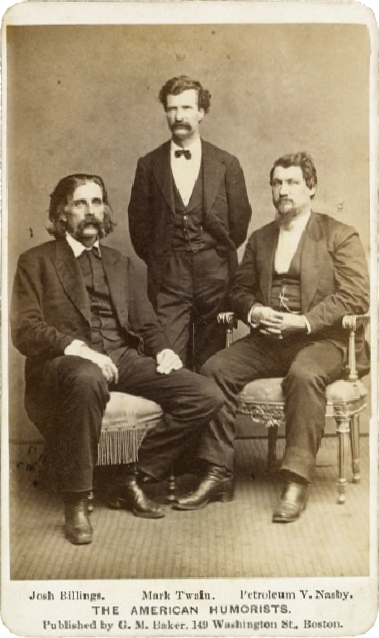

You’ve probably never heard of Josh Billing, the pen name of 19th-century American humorist Henry Wheeler Shaw (April 21, 1818 – October 14, 1885). But in his day — the latter half of the 19th century — he was a pretty famous humorist and lectured throughout the United States. In terms of his fame, he was “perhaps second only to Mark Twain,” though his legacy has not endured nearly as well as Twain’s.

Shaw was born in Lanesborough, Massachusetts on April 21, 1818. His father was Henry Shaw, who served in the United States House of Representatives from 1817–21, and his grandfather Samuel Shaw who also served in the U.S. Congress from 1808–1813. His uncle was John Savage, yet another Congressman.

Shaw attended Hamilton College, but was expelled in his second year for removing the clapper of the campus bell. He married Zipha E. Bradford in 1845.

Shaw worked as a farmer, coal miner, explorer, and auctioneer before he began making a living as a journalist and writer in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1858. Under the pseudonym “Josh Billings” he wrote in an informal voice full of the slang of the day, with often eccentric phonetic spelling, dispensing wit and folksy common-sense wisdom. His books include Farmers’ Allminax, Josh Billings’ Sayings, Everybody’s Friend, Choice Bits of American Wit and Josh Billings’ Trump Kards. He toured, giving lectures of his writings, which were very popular with the audiences of the day. He was also reputed to be the eponymous author of the “Uncle Ezek’s Wisdom” column in the Century Magazine.

In addition to wise sayings, he wrote numerous short, humorous pieces, including this odd one, entitled …

I HAV finally com tew the konclusion, that lager beer iz not intoxikatin.

I hav been told so bi a german, who sed he had drank it aul nite long, just tew tri the experiment, and was obliged tew go home entirely sober in the morning. I hav seen this same man drink sixteen glasses, and if he was drunk, he was drunk in german, and noboddy could understand it. It iz proper enuff tew state, that this man kept a lager-beer saloon, and could have no object in stating what want strictly thus.

I beleaved him tew the full extent ov mi ability. I never drank but 3 glasses ov lager beer in mi life, and that made my hed untwist, as tho it was hung on the end ov a string, but i was told that it was owing tew my bile being out ov place, and I guess that it was so, for I never biled over wuss than i did when I got home that nite. Mi wife was afrade i was agoing tew die, and i was almoste afrade i shouldn’t, for it did seem az tho evrything i had ever eaten in mi life, was cuming tew the surface, and i do really beleave, if mi wife hadn’t pulled oph mi boots, just az she did, they would have cum thundering up too.

Oh, how sick i was! it was 14 years ago, and i kan taste it now.

I never had so much experience, in so short a time.

If enny man should tell me that lager beer was not intoxikating, i should beleave him; but if he should tell me that i want drunk that nite, but that my stummuk was only out ov order, i should ask him tew state over, in a few words, just how a man felt and akted when he was well set up.

If i want drunk that nite, i had sum ov the moste natural simptoms a man ever had, and keep sober.

In the fust place, it was about 80 rods from whare i drank the lager, tew my house, and i was over 2 hours on the road, and had a hole busted thru each one ov mi pantaloon kneeze, and didn’t hav enny hat, and tried tew open the door by the bell-pull, and hickupped awfully, and saw evrything in the 417 room tryin tew git round onto the back side ov me, and in setting down onto a chair, i didn’t wait quite long enuff for it tew git exactly under me, when it was going round, and i sett down a little too soon, and missed the chair by about 12 inches, and couldn’t git up quick enuff tew take the next one when it cum, and that ain’t aul; mi wife sed i waz az drunk az a beast, and az i sed before, i begun tew spit up things freely.

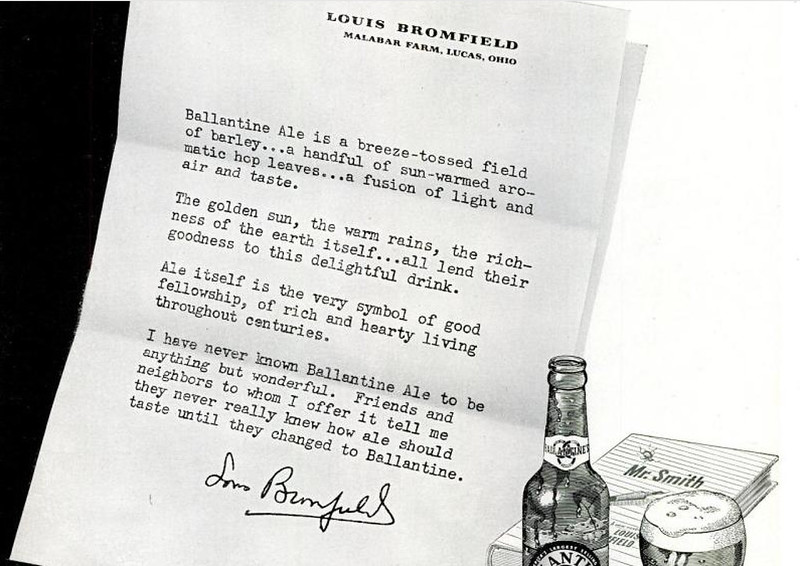

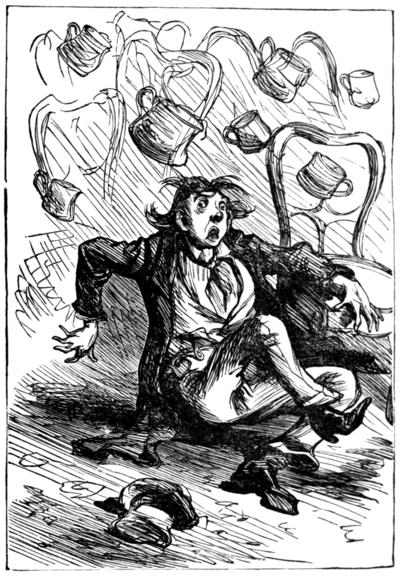

Illustration possibly by Thomas Nast.

If lager beer iz not intoxikating, it used me almighty mean, that i kno.

Still i hardly think lager beer iz intoxikating, for i hav been told so, and i am probably the only man living, who ever drunk enny when hiz bile want plumb.

I don’t want tew say ennything against a harmless tempranse bevridge, but if i ever drink enny more it will be with mi hands tied behind me, and mi mouth pried open.

I don’t think lager beer iz intoxikating, but if i remember right, i think it tastes to me like a glass with a handle on one side ov it, full ov soap suds that a pickle had bin put tew soak in.

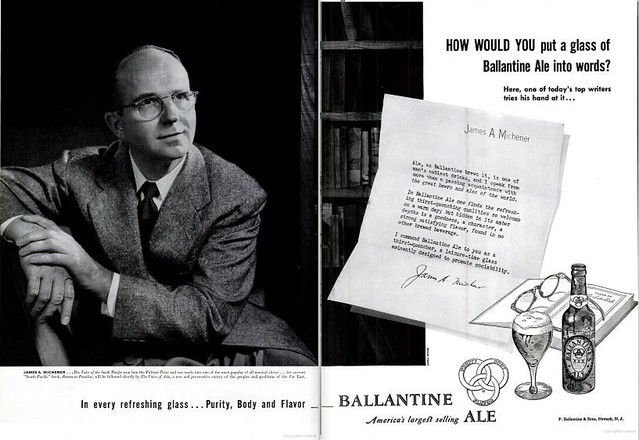

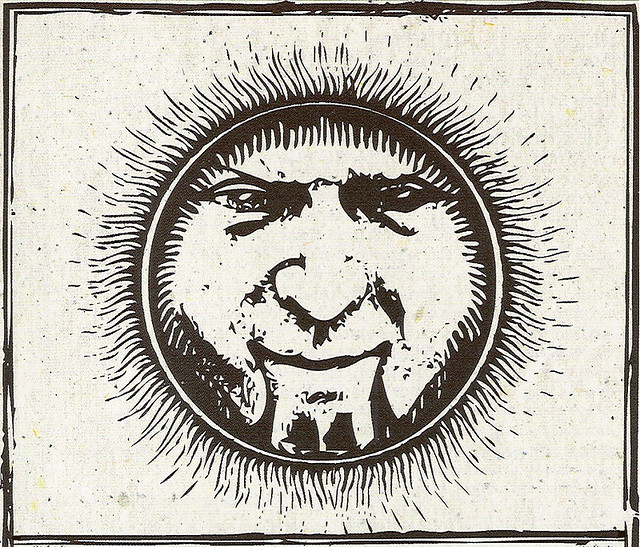

A photo of Billings with Mark Twain and political commentator Petroleum V. Nasby, photographed in Boston by G. M. Baker in November of 1869.

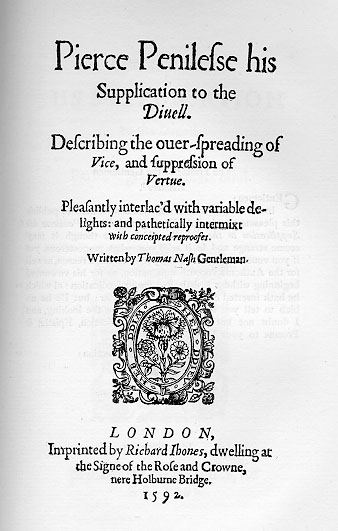

In another collection of his work, entitled “Josh Billings, Hiz Sayings: With Comic Illustrations,” published in 1865, Billings presents his definition of Lager: