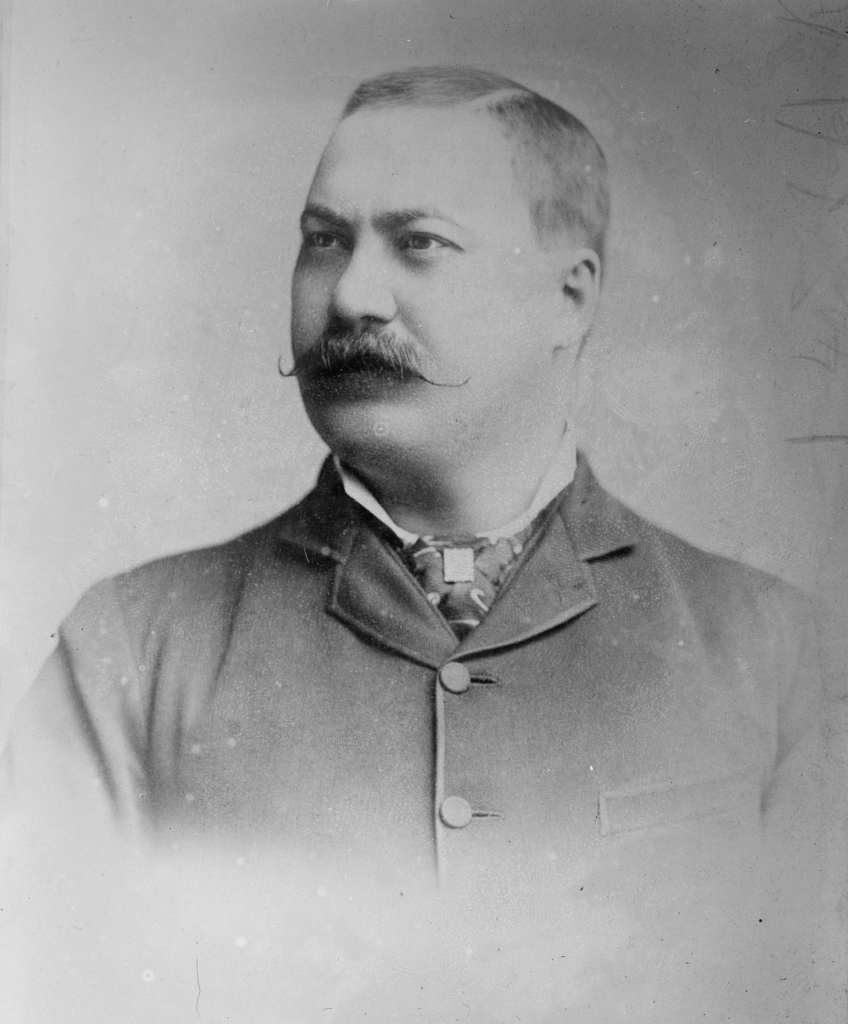

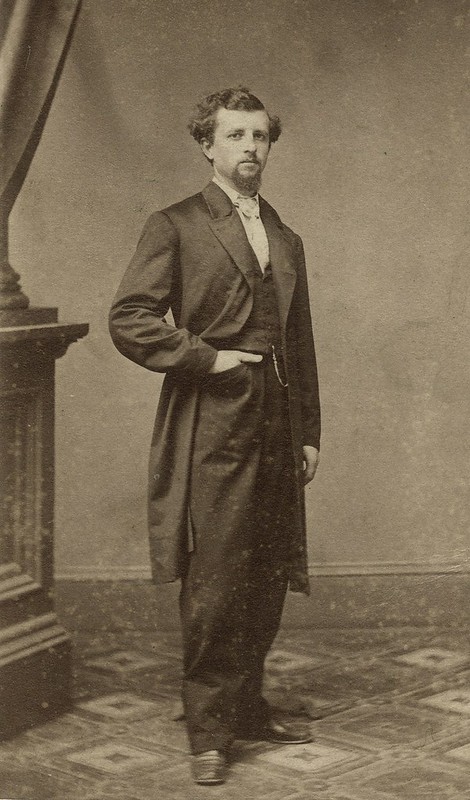

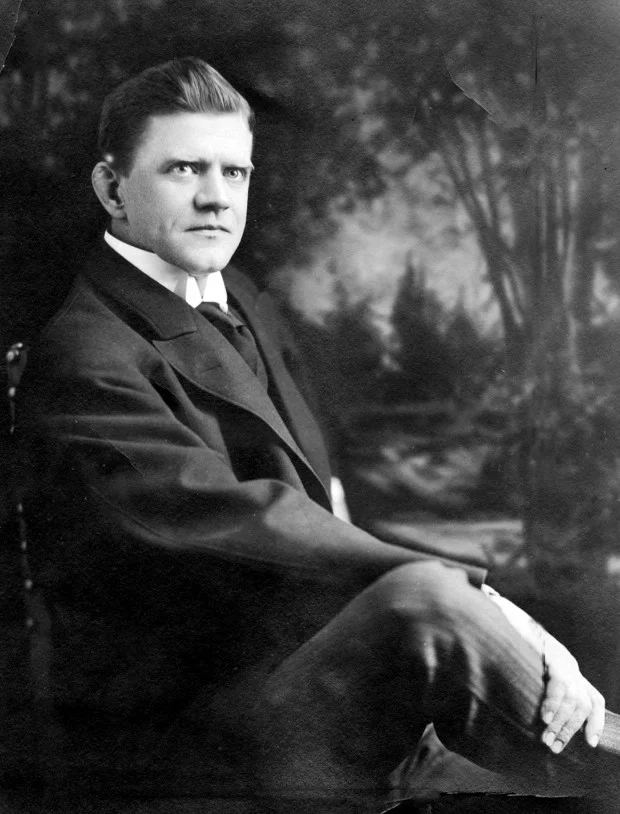

Today is the birthday of William Jacob Lemp, Jr. (August 13, 1867-December 29, 1922). He was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and was the son of William J. Lemp and the grandson of Adam Lemp, who founded the Lemp Brewery in 1840. When his grandfather died in 1862, his father inherited the brewery, and it was renamed the William J. Lemp Brewing Co. When he committed suicide, most likely from depression after his favorite son Frederick died at age 28. His other son, William J. Lemp Jr., ran the brewery thereafter, until it was closed by prohibition in 1920.

This account of Lemp Jr.’s time running the brewery is from the Wikipedia page about the Lemp Mansion:

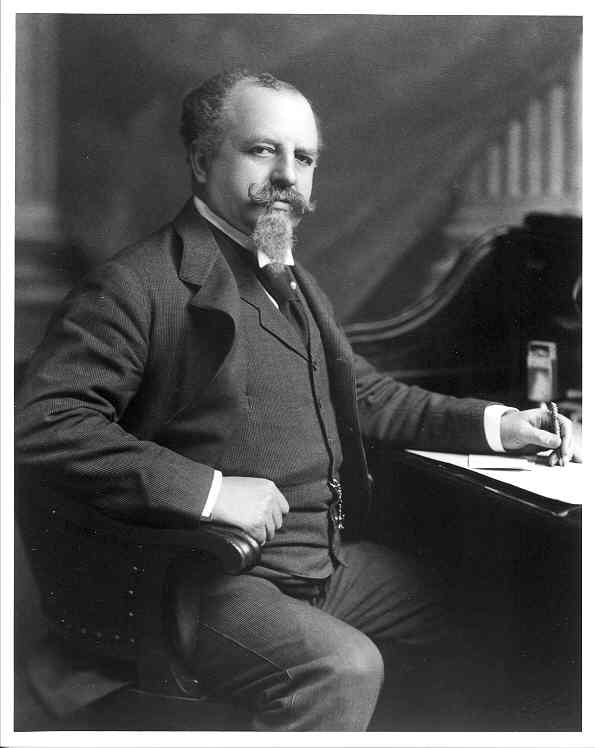

On November 7, 1904, William J. “Billy” Lemp, Jr., took over the brewing company as president. Billy had married Lillian Handlan five years earlier, and they moved to a new home at 3343 South 13th Street.

Lillian Handlan Lemp was, allegedly, nicknamed the “Lavender Lady” for her lavender-colored wardrobe and carriages. She filed for divorce in 1908, charging Billy with desertion, cruel treatment and other indignities. Their divorce proceedings lasted 11 days and ended in Lillian being granted her divorce and custody of William III – their only child – with Billy given only visitation rights.

After the trial, Billy built “Alswel” – his country home overlooking the Meramec River. The home was located in what is now the western edge of Kirkwood. By 1914, he lived at Alswel full-time.

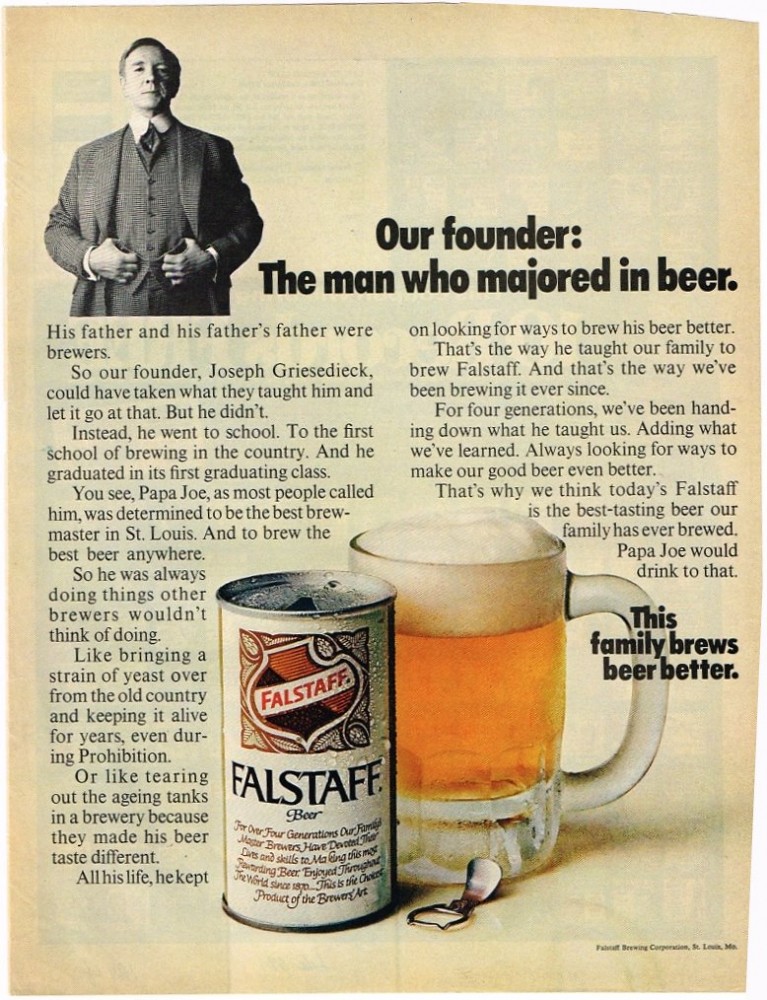

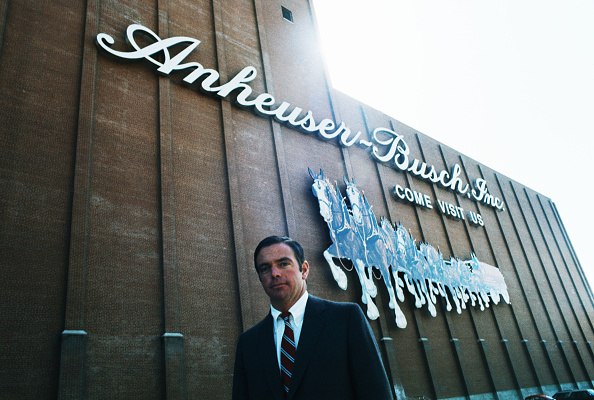

The Lemp Brewery suffered in the 1910s when Prohibition began. The brewery was shut down and the Falstaff trademark was sold to Lemp’s friend, “Papa Joe” Griesedieck. The brewery itself was eventually sold at auction to International Shoe Company for $588,500. On December 29, 1922, Billy Lemp shot himself in his office — a room that today is the front left dining room.

This history of the Lemp Family is from Monstrosity, a paranormal convention offering stays in the supposedly haunted Lemp Mansion:

America’s First Lager Beer Brewers

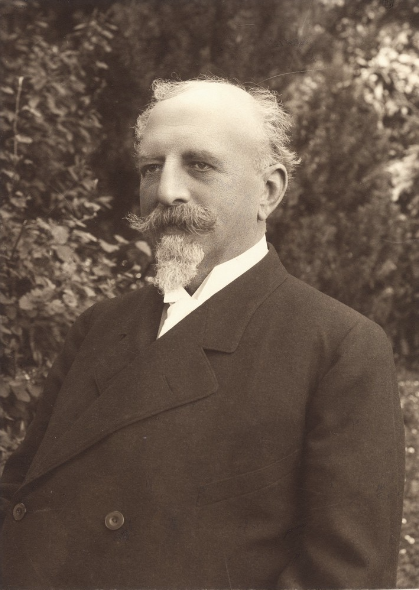

When John Adam Lemp arrived in St. Louis from Eschwege, Germany in 1838, he seemed no different from the thousands of other immigrants who poured into the Gateway to the West during the first half of the 19th century. Lemp originally sought his fortune as a grocer. But his store was unique for its ability to supply an item sold by none of his competitors – lager beer. Lemp had learned the art of brewing the effervescent beverage under the tutelage of his father in Eschwege, and the natural cave system under St. Louis provided the perfect temperature for aging beer. Lemp soon realized that the future of lager beer in America was as golden as the brew itself, and in 1840 he abandoned the grocery business to build a modest brewery at 112 S. Second Street. A St. Louis industry was born. The brewery enjoyed marvelous success and John Adam Lemp died a millionaire.

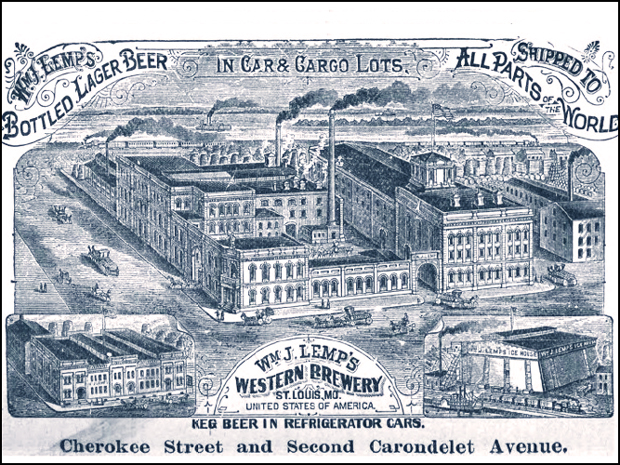

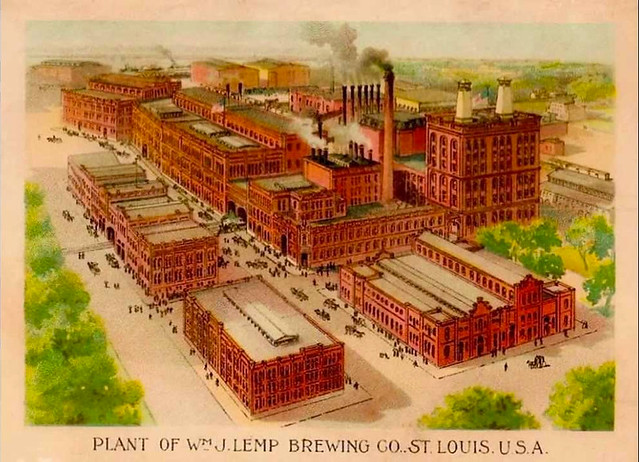

William J. Lemp succeeded his father as the head of the brewery and he soon built it into an industrial giant. In 1864 a new plant was erected at Cherokee Street and Carondolet Avenue. The size of the brewery grew with the demand for its product and it soon covered five city blocks.

In 1870 Lemp was by far the largest brewery in St. Louis and the Lemp family symbolized the city’s wealth and power. Lemp beer controlled the lion’s share of the St. Louis market, a position it held until Prohibition. In 1892 the brewery was incorporated as the William J. Lemp Brewing Co. In 1897 two of the brewing industry’s titans toasted each other when William Lemp’s daughter, Hilda, married Gustav Pabst of the noted Milwaukee brewing family.

The Lemp Family

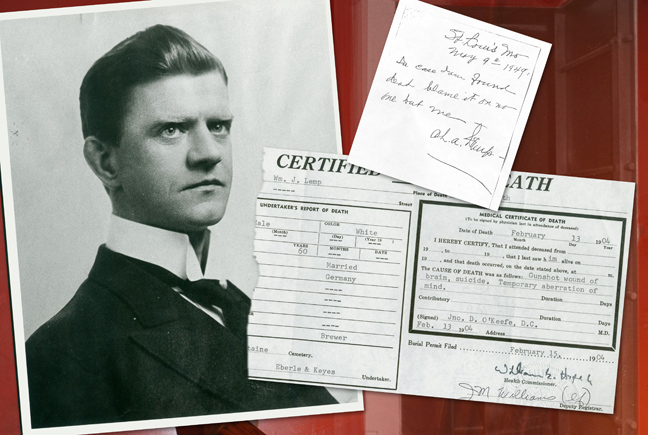

The demise of the Lemp empire is one of the great mercantile mysteries of St. Louis. The first major fissure in the Lemp dynasty occurred when Frederick Lemp, William’s favorite son and the heir apparent to the brewery presidency, died under mysterious circumstances in 1901. Three years later, William J. Lemp shot himself in the head in a bedroom at the family mansion, apparently still grieving the loss of his beloved Frederick. William J. Lemp, Jr. succeeded his father as president.

Tragedy continued to stalk the Lemps with startling ardor. The brewery’s fortunes continued to decline until Prohibition (1919) closed the plant permanently. William Jr.’s sister Elsa, who was considered the wealthiest heiress in St. Louis, committed suicide in 1920. On June 28, 1922, the magnificent Lemp brewery, which had once been valued at $7 million and covered ten city blocks, was sold at auction to International Shoe Co. for $588,500. Although most of the company’s assets were liquidated, the Lemps continued to have an almost morbid attachment for the family mansion. After presiding over the sale of the brewery, William J. Lemp, Jr. shot himself in the same building where his father died eighteen years earlier. His son, William Lemp III, was forty-two when he died of a heart attack in 1943. William Jr.’s brother, Charles, continued to reside at the house after his brother’s suicide. An extremely bitter man, Charles led a reclusive existence until he too died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. The body was discovered by his brother, Edwin.

In 1970, Edwin Lemp died of natural causes at the age of ninety.

Not everyone is convinced that Junior’s death was a suicide, but may have been murder, as explained in All Things Lemp:

On December 28th, 1922 William Lemp Jr. was found shot to death in his office on the first floor of the Lemp Mansion. William Lemp Jr. was not a very well liked person. Junior’s personality was rather crass and abrupt. Most people who knew him would avoid him if all possible. Junior was not the first pick by his father to inherit the Lemp Brewery Presidency. This had to be embarrassing considering Junior was the oldest and by tradition the heir apparent. This honor was to be reserved for his youngest brother Fredrick. The reason why Junior was to be passed over to run the family’s brewing empire was the standing animosity between Junior and his father. Many think Senior despised his oldest son because he thought William Lemp Junior didn’t deserve to bear his name. Very few people at the time knew that William Lemp Jr. had an older brother that died shortly after birth. It pained his father deeply that the child died before it could be named. His father thought his first deceased son should have been given his name, not his second surviving son. This is believed to be the initial cause of their life long feud. Fredrick died in 1901 due to heart failure. If Fredrick would have survived, many think that we would have a Lemp Brewery today.

According to police reports, William Lemp Jr. was shot twice directly into the heart with a .38 caliber single action revolver. In order for someone to pull off a feat such as this, one would have to be able to pull the trigger twice. With a single action revolver, that would mean that he would have to cock the pistol, place it to his chest, and pull the trigger. Then he would have to repeat the process of cocking the revolver again, placing it to his chest, and pulling the trigger. I doubt seriously that anyone would have the ability to be able to shot themselves twice in the chest with this style of weapon. Especially after the initial shot would leave a rather large wound in your back and in shock. The police also found two rounds missing from the revolver’s cylinder. If he was shot twice, it there is a very good chance William Lemp Jr. was murdered.

The Coroner’s report states he was shot only once. If the Coroner is right it could have very well been a suicide. Since the findings of a Coroner’s inquiry outweighs the evidence presented by the police, the death of William Lemp Jr. was ruled a suicide, and the case was closed.

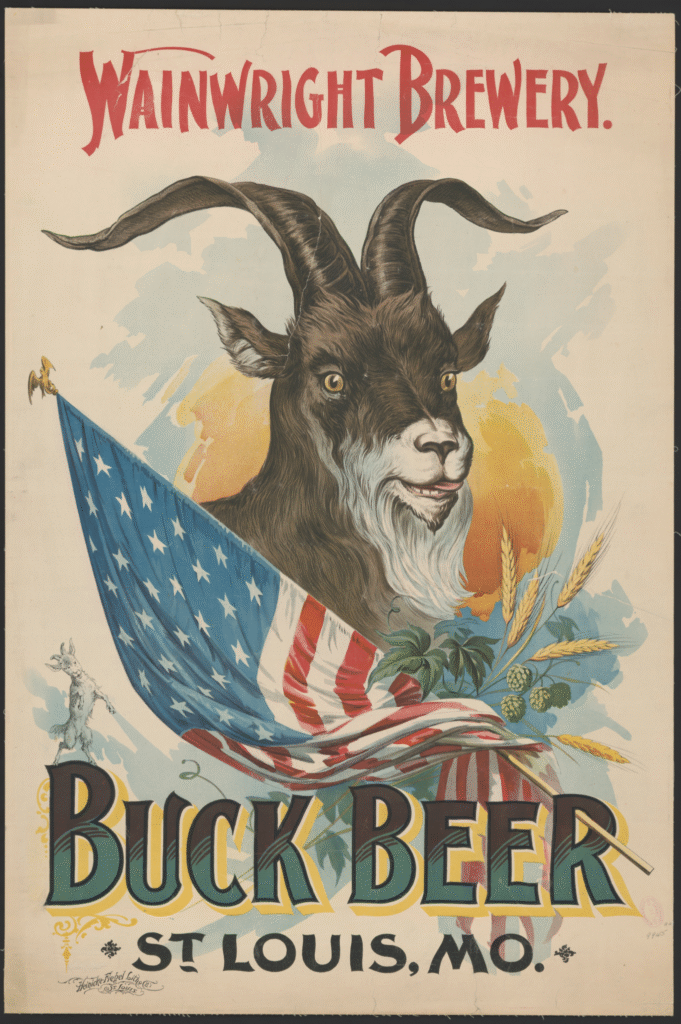

This is a slideshow of Lemp breweriana and photos.