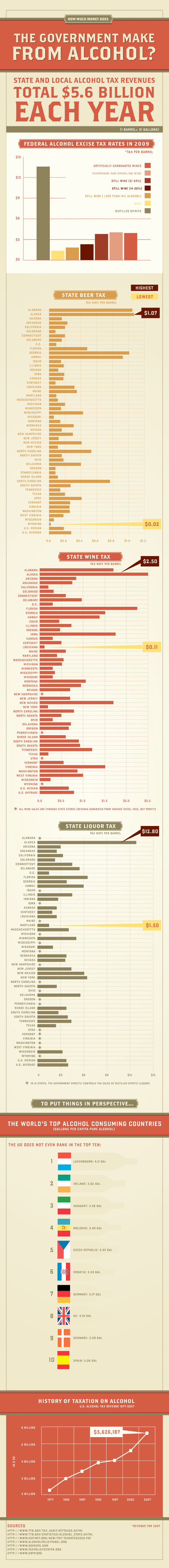

Given that the anti-alcohol folks, and especially my churlish neighbors Alcohol Justice, are continually beating the drum about alcohol taxes being too low, this news is not going to be particularly welcomed with open arms. A British think tank, the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), recently took a close look at the effect of higher taxes in alcohol and their report, Drinking in the Shadow Economy, found that the British “Treasury is losing as much as £1.2 billion every year to the illegal alcohol industry.” That, they conclude, is one of the effects of higher taxes on alcohol, because it creates an incentive for people to go outside the law and the safe world of regulated alcohol to make a quick buck. They found that “the illicit alcohol market is also closely associated with high taxes, corruption and poverty. The affordability of alcohol appears to be the key determinant behind the supply and demand for smuggled and counterfeit alcohol.” So place too high taxes on alcohol, and you invite in the wrong element, which we’ve seen in the U.S. before during Prohibition, and which we’re seeing right now with the war on drugs. If that futile policy was reversed, we’d save as much $13.7 billion annually by legalizing, regulating and taxing just marijuana, not to mention we’d remove the criminal element, make it safer and drastically reduce burdens on police, the justice system and prisons.

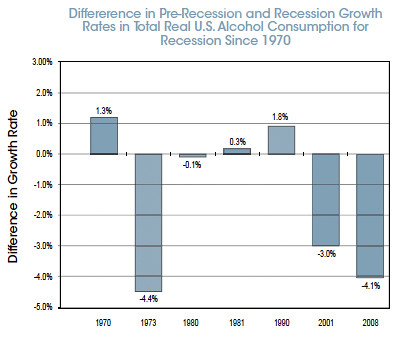

But back across the pond, the study also notes that the “demand for alcohol is relatively inelastic,” meaning people generally don’t drink less when prices go up, they instead find new ways to address the rising prices. As study after study has concluded, tax hikes are regressive and almost always hit poorer families the hardest, while not eliminating the problem the proponents of such measures claim they will fix.

But here’s that again, said another way:

Our analysis indicates that the affordability of alcohol does not have a strong effect on how much alcohol is consumed. Once unrecorded alcohol is included in the estimates, it can be seen that countries with the least affordable alcohol have the same per capita alcohol consumption rates as those with the most affordable alcohol.

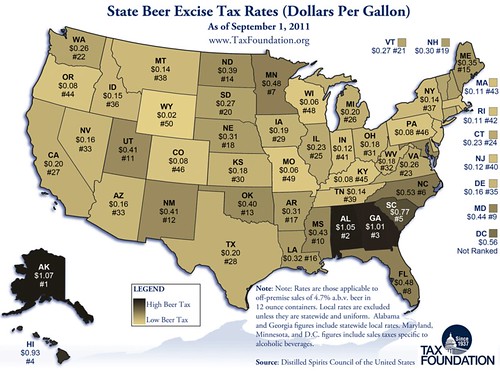

I suspect that’s the case here, too. We know that price hikes cause people living near borders with other states to simply buy their alcohol in the next state over, causing further economic erosion. I don’t know if we have the same issue with counterfeit or illegal beer. Certainly there’s still Moonshine, but beer is probably not profitable enough on its own to warrant illegal breweries flaunting the tax code, not to mention how labor intensive and technology-dependent it is.

Another interesting portion of the report, answering the question “Why Tax Alcohol?”

Temperance and public health campaigners typically dismiss the black market as a problem that can suppressed through rigorous enforcement and tougher sentencing. At worst, they view a growing unofficial market as a price worth paying for a more sober society. This view is rooted in the belief that affordability is the main driver of alcohol consumption and that increasing prices by raising excise duty is therefore the single most effective way of reducing alcohol sales.

Ceteris paribus, economists would expect there to be some truth in this assertion, but there is too much real world evidence to the contrary for it to be taken as an iron rule. For example, alcohol consumption has fallen in most European countries since 1980 despite alcohol becoming significantly more affordable (OECD, 2011: 275).19 In Denmark, Sweden and Finland, the sudden drop in alcohol prices that resulted from EU accession did not bring about the kind of surge in alcohol consumption that the price elasticity models predicted.

A comparison of European countries suggests that affordability has a negligible and statistically insignificant negative effect on recorded alcohol consumption (see Figure 12). Moreover, as Figure 13 shows, when unrecorded alcohol consumption is included in the analysis, affordability does not appear to be a decisive factor in determining alcohol consumption from one country to the next.

Then there’s this long passage addressing some of the philosophy behind taxation which seems to fly in the face of much of the neo-prohibitionists propaganda playbook:

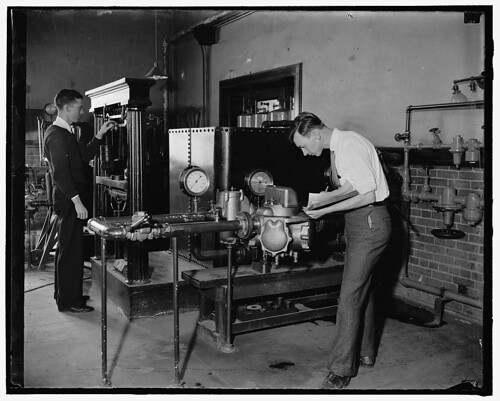

Contrary to temperance rhetoric, high alcohol taxes are not necessarily good for public health because, although excessive alcohol consumption undoubtedly carries risks to health, so too does moonshine. Counterfeit spirits and surrogate alcohol frequently contain dangerous levels of methanol, isopropanol and other chemicals which cause toxic hepatitis, blindness and death. These are the unintended consequences one associates with prohibition, albeit at a less intense level than was seen in America in the 1920s.

It should not be surprising that excessive taxation encourages the same illicit activity as prohibition since the difference is only one of degrees. As John Stuart Mill noted in 1859: ‘To tax stimulants for the sole purpose of making them more difficult to be obtained is a measure differing only in degree from their entire prohibition, and would be justifiable only if that were justifiable. Every increase of cost is a prohibition to those whose means do not come up to the augmented price’ (Mill, 1974: 170-171).

But in a less frequently quoted passage, Mill appears to approve of taxing alcohol to the apex of what we now call the Laffer Curve. Appreciating that governments need to raise funds and that these politicians must decide ‘what commodities the consumers can best spare’, Mill argues that taxation of stimulants ‘up to the point which produces the largest amount of revenue (supposing that the State needs all the revenue which it yields) is not only admissible, but to be approved of’ (Mill, 1974: 171).

This message tends to resonate more powerfully with politicians than Mill’s more libertarian pronouncements. Drinkers generally prefer low alcohol prices. Temperance campaigners nearly always demand higher prices. The politician, however, usually seeks to maximise tax revenues and will only react to the shadow economy when it becomes a serious threat to state finances. Nordlund and Österberg summarise the politician’s dilemma as follows:

‘Domestic economic actors can, of course, support the rules and regulations imposed by the state for controlling unrecorded alcohol consumption, but for these actors a better solution in combating unrecorded alcohol consumption would be the lowering of alcohol excise taxes… In most cases the state is not willing to follow this policy, as lower alcohol excise taxes in most cases mean lower levels of alcohol-related tax incomes. However, if the state is no longer able to control the amount of unrecorded alcohol consumption by different kinds of legal administrative restrictions the only remaining way to counteract, for instance, huge increases in travellers’ border trade with alcoholic beverages or an expansive illegal alcohol market is to lower the price difference between unrecorded and recorded alcohol by decreasing excise taxes on alcoholic beverages.’ (Nordlund, 2000: S559)

It scarcely matters to the politician whether unrecorded alcohol comes from legal or illegal sources. In either case, the treasury loses out on revenue. In Britain, HMRC estimates that the alcohol tax gap could be as much as £1.2 billion per annum, plus the costs of enforcement, and that this is largely because ‘duty rates on alcohol are far higher in the UK than in mainland Europe’ (National Audit Office, 2012: 2, 10). This is the price the state must pay for excessive taxation, but the politician is also aware that these high alcohol taxes raise £9 billion a year (Collis, 2010: 3). Being in possession of these facts he may conclude that reducing the illicit alcohol supply through tax cuts will probably reduce net alcohol tax revenues.

We argue that such a focus on maximising tax revenues is short-sighted and carries significant risks. Failing to deal with alcohol’s shadow economy threatens not only the public finances, but also public health and public order. Unrecorded alcohol has, as Nordlund and Österberg note, ‘the potential to lead to political, social and economic problems’ (Nordlund, 2000: S562). In addition to the health hazards presented by unregulated spirits, alcohol fraud in the UK is, according to the HMRC, ‘perpetrated by organised criminal gangs smuggling alcohol into the UK in large commercial quantities’ (HMRC, 2012: 8). Alcohol smuggling and counterfeiting is linked to other illegal activities, including drug smuggling, prostitution, violence, money-laundering and — in a few instances — terrorism.

Incidentally, you can download a pdf of the entire report here, and at the IEA website.

In the press release, the IEA concludes:

“The government’s focus on maximising tax revenues is short-sighted and dangerous. Aside from losing money by encouraging consumers to find cheaper illicit alternatives, public health and public order are also being put at risk by high prices. Policy-makers ought to take the threat of illicit alcohol production seriously when considering alcohol pricing in the future.”

“There is a clear relationship between the affordability of alcohol and the size of the black market. Politicians might view the illicit trade as a price worth paying for lower rates of alcohol consumption, but this research shows that the amount of drink consumed in high tax countries is exactly the same as in low tax countries.”

“Minimum alcohol pricing might seem like a quick fix to tackle problem drinking, but it is likely to cause many more problems by pushing people towards the black market in alcohol.”

While a fairly emphatic statement against higher taxes on alcohol, I assume that many will still wonder how applicable it is to the United States economy and society. Honestly, I’m sure there are differences, but the overall concept seems sound, at least to me. We can haggle over some of the details, but the idea that higher taxes isn’t always the answer just has the ring of truth to it.