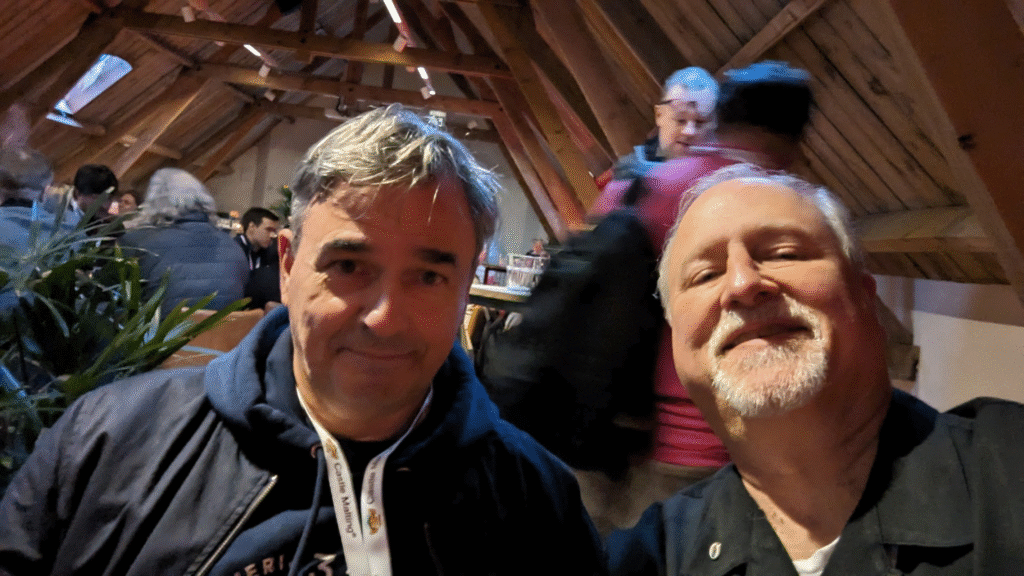

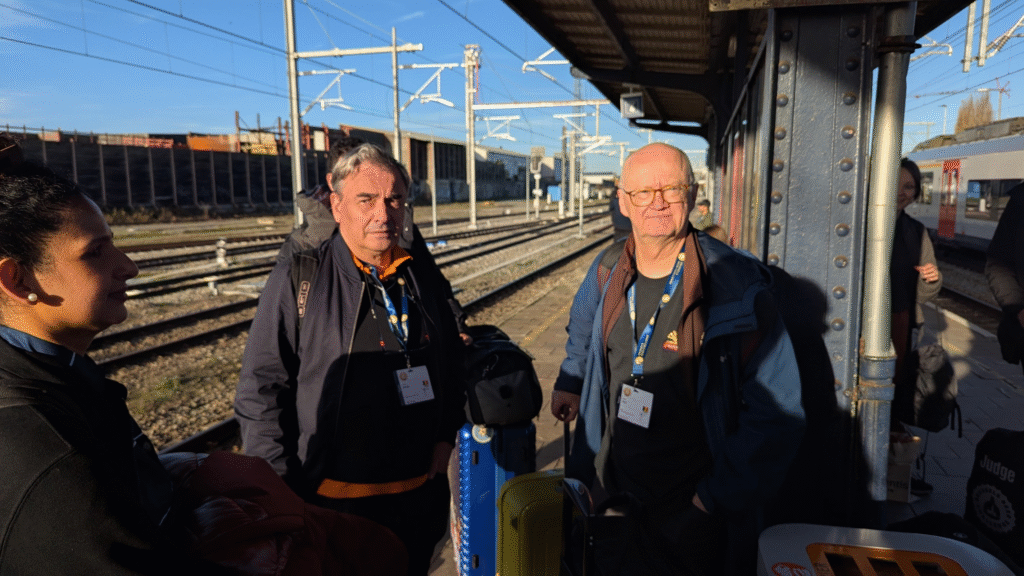

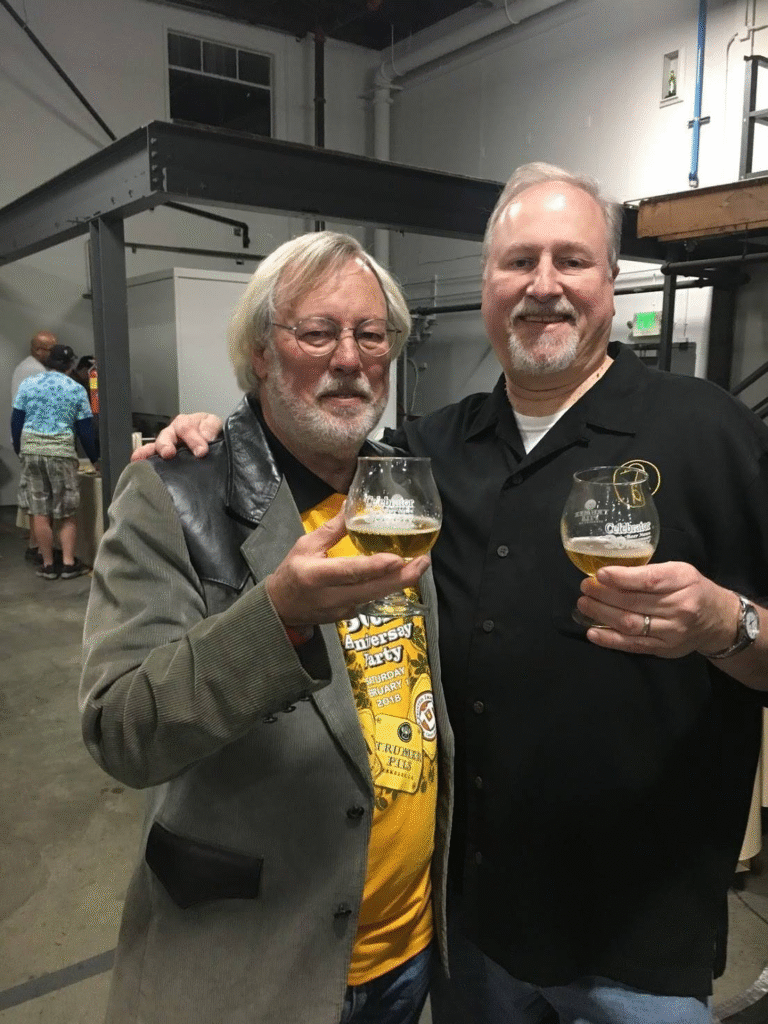

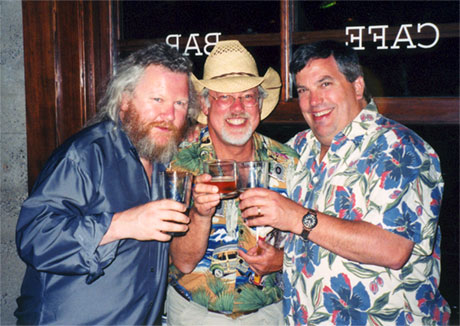

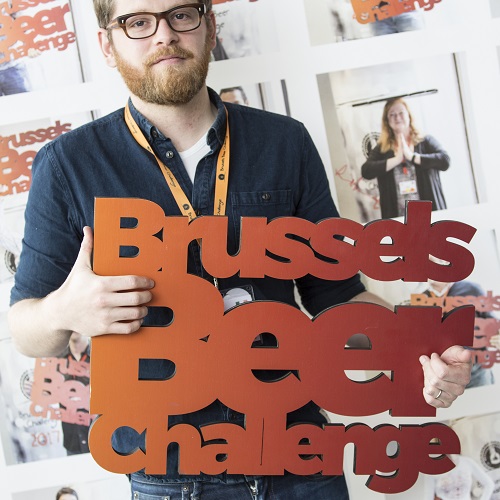

Today is the 46th birthday of John Holl, a journalist who spent the early part of his career working the crime and politics beat at various newspapers, including the New York Times. Now, he’s writing almost exclusively about beer from his home in northern New Jersey. He was the editor of All About Beer Magazine and has worked for most of the trade publications in some capacity over the years. He’s also written several books including the American Craft Beer Cookbook and the Craft Brewery Cookbook. In recent years he’s done a number of podcasts including Drink Beer, Think Beer, Steal This Beer, and The BYO Nano Podcast. In 2019 he founded the site Beer Edge with Andy Crouch and more recently they bought All About Beer magazine. He also works as a contributing editor at Wine Enthusiast Magazine. I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know John during some travel over the years, from Denver to Boston, Brussels, and even in Chile. He’s been a great addition to the fraternity of beer writers. Join me in wishing John a very happy birthday.

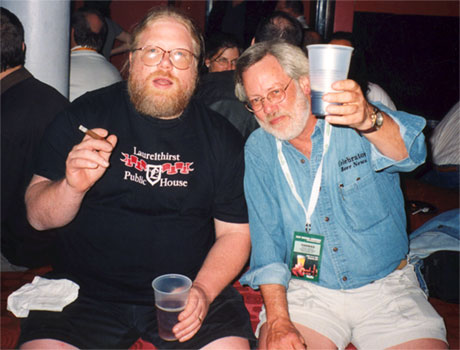

With Stephen Beaumont and Stan Hieronymous, taking a pizza from Sandlot Brewing to Great Divide during GABF a few years ago.