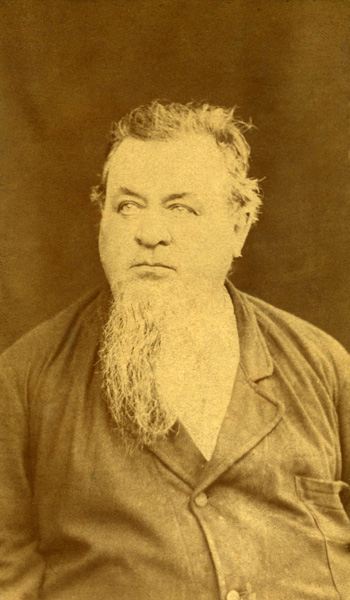

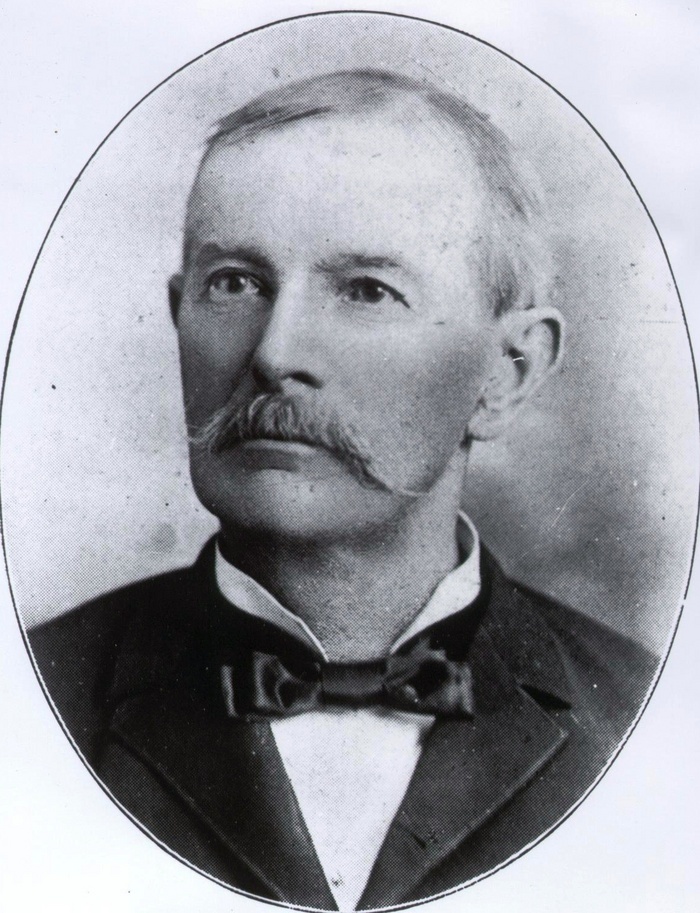

Today is the birthday of Philip Zang (February 15, 1826-February 18, 1899) who’s most remembered for his brewery in Denver, Colorado, although he also founded a brewery in Louisville, Kentucky, before moving west in 1869. He was born in Bavaria, Germany, but came to the U.S. in 1853.

Here’s a short biography from Find a Grave:

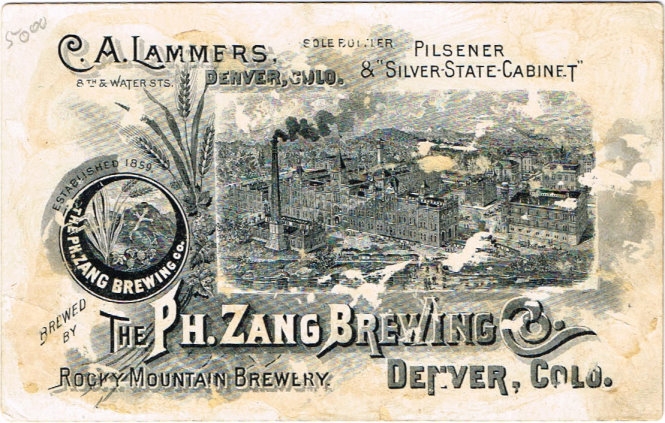

Brewing Magnate in Denver. Owner of first brewery in Denver, Rocky Mountain Brewery, which was also the largest west of the Mississippi from 1880 to the start of prohibition. Arrived in the USA in 1853; initially settled in Louisville, Kentucky where he owned Phoenix Brewery (later Zang Brewing Co.), the largest in Kentucky, for 16 years; relocated to Denver in September 1869; acquired Rocky Mountain Brewery in 1871 and changed its name to Philip Zang Brewing Co.; increased production over the years to achieve over 65,000 barrels per year while surviving a couple of destructive fires; sold Philip Zang Brewing Co. in 1888 to British investors; retired from brewing in 1889 and listed the same year as one of 33 millionaires living in Denver. Was involved in mining holding interests in a number of gold and silver mines in Silverton, Cripple Creek and Eagle County. A prominent Denver citizen, he was also elected as a democrat to a term as city alderman.

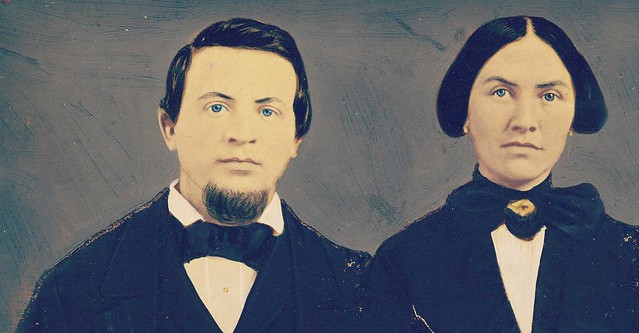

PHILIP ZANG, founder of the Ph. Zang Brewing Company, of Denver, was a native of Bavaria, Germany, immigrated to United States in by ship in 1853. Married Elizabeth Hurlebaus, who died in Chicago, leaving an only child, Adolph J. Zang.

- Founded Phoenix brewery in Louisville (1859-1869) then moved to Denver

- Bought Rocky Mountain Brewing Co. from John Good (1871)

- Changed name to Philip Zang & Co. (7/1880)

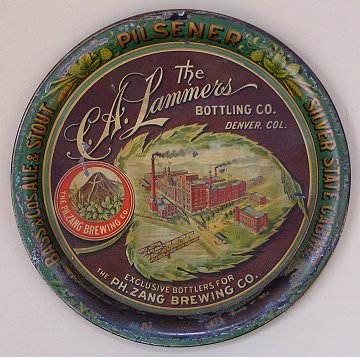

- Sold to UK syndicate-chg. name to PH. Zang Brewing Co. (1889)

- Son; Adolf J. Zang took over management (General Manager)

- Second Marriage (10/1870) to Mrs. Anna Barbara Buck, nee Kalberer, (b.1836)(d.4/1896)

- Previously widowed from marriage to Jacob Buck (b.1832) m(1857-xxxx)

- The family residence, built in 1887, was at 2342 Seventh street, Denver, CO

ROOTS

Philip Zang, founder of the PH. Zang Brewing Company, of Denver, was a native of Bavaria, Germany, and next to the oldest among the six sons and two daughters of John and Fredericka (Kaufman) Zang. His father, who was a member of an old Bavarian family, engaged in farming and the milling business, and took part in the Napoleonic wars, accompanying the illustrious general on his march to Moscow. He (John) died in 1849, at the age of sixty-two. Two of John and Fredericka’s sons, Alexander and Philip, immigrated to America. During the Civil War Alexander served in the Thirty-ninth New York Infantry; he died in Denver in 1892.

BOUND FOR AMERICA

Philip was a brewer’s apprentice for two and one-half years, after which he traveled around Germany, working at his trade. In 1853 he came to America, going from Rotterdam to Hull, then to Liverpool, and from there on the “City of Glasgow,” which landed him in Philadelphia after a voyage of eighteen days.

LEAPING FORWARD

Ignorant of the English language, his first endeavor was to gain sufficient knowledge to converse with the people here, and during the first six months in this country, while working as a railroad hand, he was storing in his mind a knowledge of our customs and language. In Philadelphia Mr. P. Zang married Miss Elizabeth Hurlebaus, who died in Chicago, leaving an only child, Adolph J. Zang. In January 1854, he went to Louisville, Ky., where he worked at his trade for one year. Later, desiring to learn engineering, he secured employment in a woolen mill, and remained there until January 1859, meantime becoming familiar with the engineer’s occupation.

THE BREWERY BUSINESS

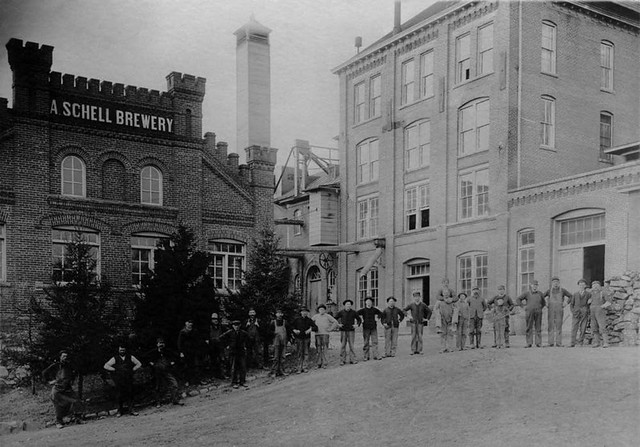

Mr. P. Zang built a brewery in Louisville and this he conducted alone until 1865, when he erected a large brewery, which was carried on under the firm name of Zang & Co. Selling this in February 1869; he decided to locate in the growing town of Denver.

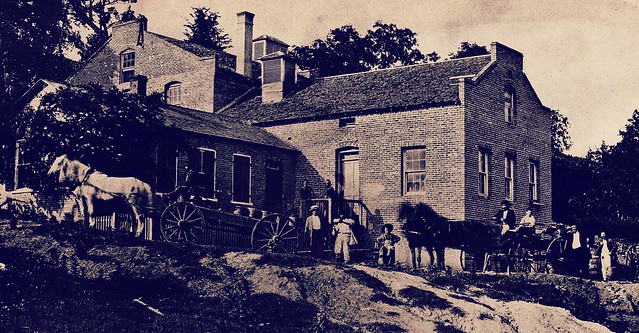

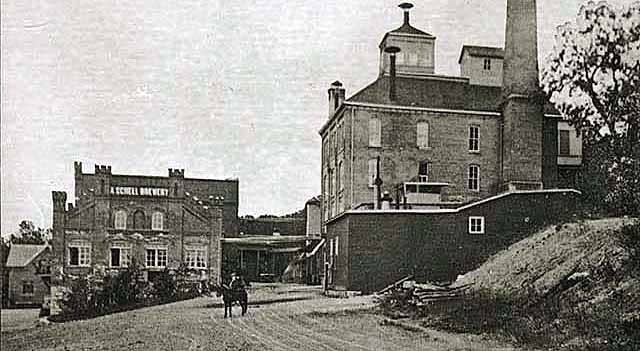

Here he was engaged as superintendent of the brewery owned by John Good until July 1871, when he bought out his employer and continued the business alone. Mr. Good had started the business in 1859 on the same spot, under the title of the Rocky Mountain Brewery, which continued to be its name for some years. In July 1871, Mr. Zang enlarged the brewery, which then had a capacity of one hundred and fifty thousand barrels per annum, and is the largest between St. Louis and San Francisco. There was also a malt house, with modern equipments; an ice plant, lager beer vaults, boiler house, brewery stables, and a switch from the railroad connecting with the main lines, in order to facilitate the work of shipment. In 1880 the name was changed to Philip Zang & Co., and in July 1889, the business was sold to an English syndicate, who changed the name to the Ph. Zang Brewing Company.

LOCAL AFFAIRS

In Denver, October 18, 1870, he was united in marriage with Mrs. Anna B. Buck, nee Kalberer, an estimable lady and one who has many friends in this city. The family residence, built in 1887, stood at 2342 Seventh street. For one term Mr. Zang served as an alderman of the sixth ward, to which position he was elected on the Democratic ticket, but he himself is independent in politics. While in Louisville he was made a Mason and an Odd Fellow, and he belonged to Schiller Lodge No. 41, A. F. & A. M., and Germania Lodge No. 14, I. O.O. F., of Denver, of both of which he was a charter member. He was also connected with the Turn Verein, Krieger Verein and Bavarian Verein, and took a prominent part in all local affairs.

And in this short account, it is suggested it was gold fever that enticed Zang west, and when that didn’t pan out, he returned to what he knew: brewing beer.

“Zang came to Denver in 1870 – a few years after the Civil War – having run the Phoenix Brewery in Louisville Kentucky for 16 years. Even though his brewery had thrived through the turmoil of the war, he caught gold fever, sold that brewery and headed west. His gold mining career in Leadville lasted about a month. Soon he found himself back in the more palatable environment of Denver, running the Rocky Mountain Brewery for a “Capitalist” (his official title) called John Good. Within a couple years, Zang bought the brewery from Good and soon increased its capacity ten-fold. From then until the complication of Prohibition in 1920, Zang Brewing Company was the largest beer producer west of the Missouri.”

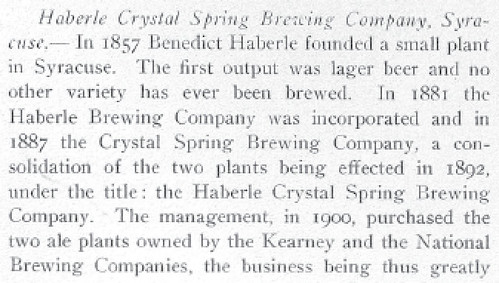

The wonderful book 100 Years of Brewing, published in 1901, also has a short account of Zang’s brewery: