Today, just over three-hundred years ago — July 23, 1716 — a little-known historical event took place in London, known as the Mug-House Riots, between Jacobite and Hanoverian partisans.

One of my favorite old books on dates, entitled “Chamber’s Book of Days,” which was published in England, in 1869, has an account of the Mug-Houe Riots:

On the 23rd of July 1716, a tavern in Salisbury Court, Fleet Street, was assailed by a great mob, evidently animated by a deadly purpose. The house was defended, and bloodshed took place before quiet was restored. This affair was a result of the recent change of dynasty. The tavern was one of a set in which the friends of the newly acceded Hanover family assembled, to express their sentiments and organise their measures. The mob was a Jacobite mob, to which such houses were a ground of offence. But we must trace the affair more in detail.

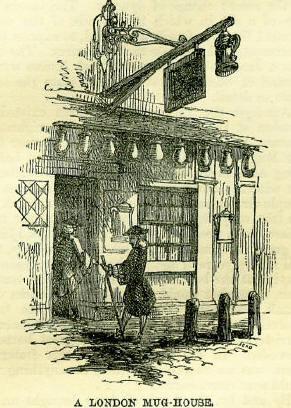

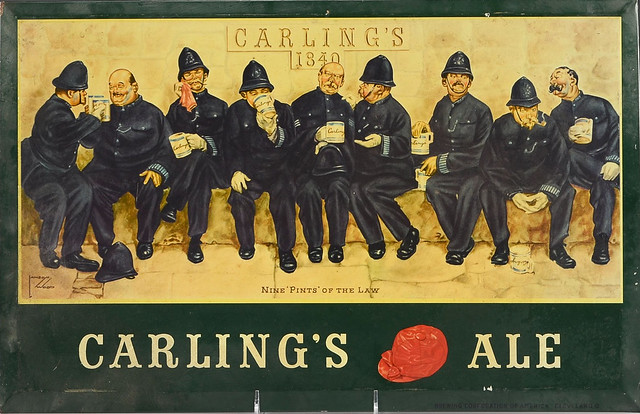

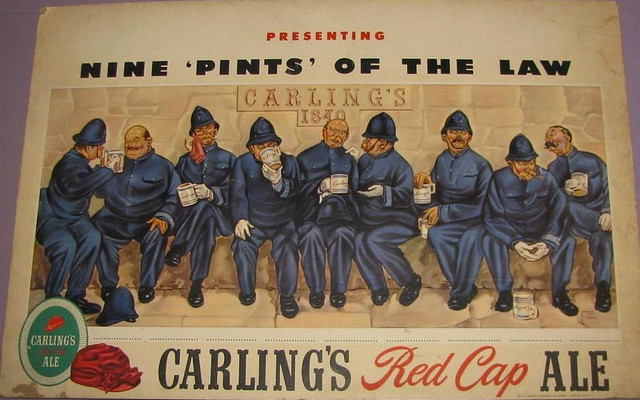

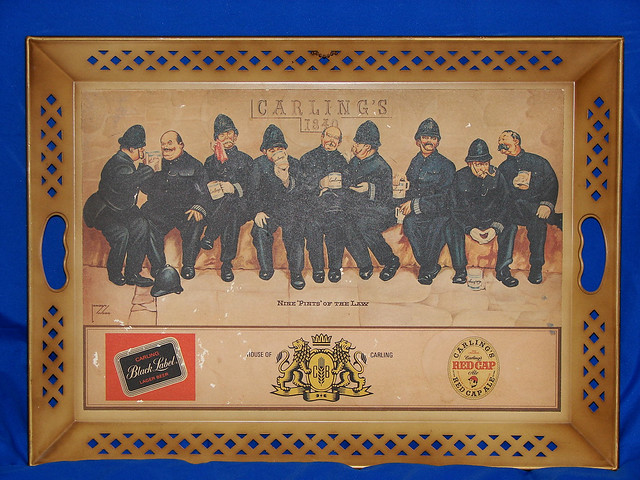

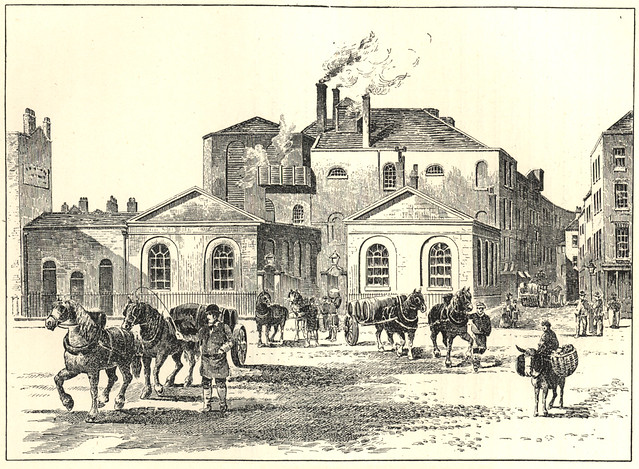

Amongst the various clubs which existed in London at the commencement of the eighteenth century, there was not one in greater favour than the Mug-house Club, which met in a great hall in Long Acre, every Wednesday and Saturday, during the winter. The house had got its name from the simple circumstance, that each member drank his ale (the only liquor used) out of a separate mug. There was a president, who is described in 1722 as a grave old gentleman in his own gray hairs, now full ninety years of age.’ A harper sat occasionally playing at the bottom of the room. From time to time, a member would give a song. Healths were drunk, and jokes transmitted along the table. Miscellaneous as the company was—and it included barristers as well as trades-people—great harmony prevailed. In the early days of this fraternity there was no room for politics, or anything that could sour conversation.

By and by, the death of Anne brought on the Hanover succession. The Tories had then so much the better of the other party, that they gained the mob on all public occasions to their side. It became necessary for King George’s friends to do something in counteraction of this tendency. No better expedient occurred to them, than the establishing of mug-houses, like that of Long Acre, throughout the metropolis, wherein the friends of the Protestant succession might rally against the partizans of a popish pretender. First, they had one in St. John’s Lane, chiefly under the patronage of a Mr. Blenman, a member of the Middle Temple, who took for his motto, ‘Pro rege et loge;’ then arose the Roebuck mug-house in Cheapside, the haunt of a fraternity of young men who had been organised for political action before the end of the late reign. According to a pamphlet on the subject, dated in 1717,

‘The next mug-houses opened in the city were at Mrs. Read’s coffee-house in Salisbury Court, in Fleet Street, and at the Harp in Tower Street, and another at the Roebuck in Whitechapel. About the same time, several other mug-houses were erected in the suburbs, for the reception and entertainment of the like loyal societies; viz., one at the Ship, in Tavistock Street, Covent Garden, which is mostly frequented by loyal officers of the army; another at the Black Horse, in Queen Street, near Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, set up and carried on by gentlemen, servants to that noble patron of loyalty, to whom this vindication of it is inscribed [the Duke of Newcastle]; a third was set up at the Nag’s Head, in James’s Street, Covent Garden; a fourth at the Fleece, in Burleigh Street, near Exeter Exchange; a fifth at the Hand and Tench, near the Seven Dials; several in Spittlefields, by the French refugees; one in Southwark Park; and another in the Artillery Ground.’ Another of the rather celebrated mud houses was the Magpie, without Newgate, which still exists in the Magpie and Stump, in the Old Bailey. At all of these houses it was customary in the forenoon to exhibit the whole of the mugs belonging to the establishment in a range over the door—the best sign and attraction for the loyal that could have been adopted, for the White Horse of Hanover itself was not more emblematic of the new dynasty than was—the Mug.

It was the especial age of clubs, and the frequenters of these mug-houses formed themselves into societies, or clubs, known generally as the Mug-house Clubs, and severally by some distinctive name or other, and each club had its president to rule its meetings and keep order. The president was treated with great ceremony and respect: he was conducted to his chair every evening at about seven o’clock, or between that and eight, by members carrying candles before and behind him, and accompanied with music. Having taken a seat, he appointed a vice-president, and drank the health of the company assembled, a compliment which the company returned. The evening was then passed in drinking successively loyal and other healths, and in singing songs. Soon after ten, they broke up, the president naming his successor for the next evening, and, before he left the chair, a collection was made for the musicians.

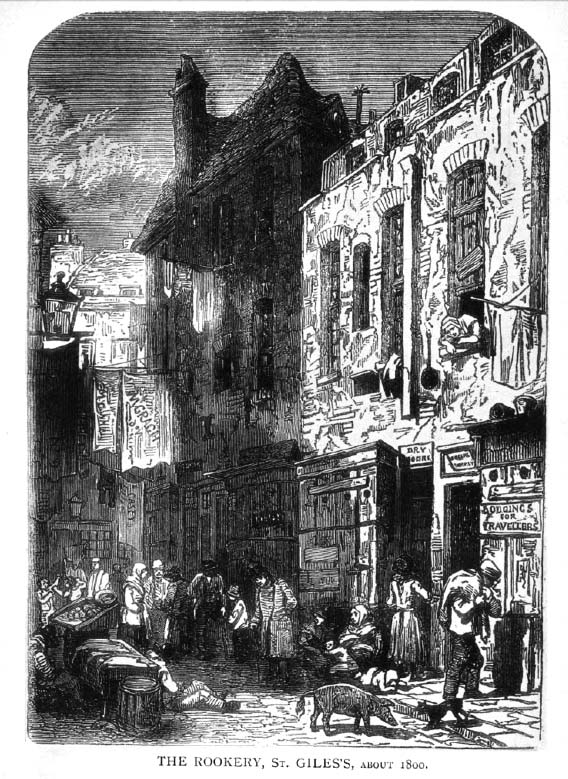

These clubs played a very active part in the violent political struggles of the time. The Jacobites had laboured with much zeal to secure the alliance of the street-mob, and they had used it with great effect, in connection with Dr. Sacheverell, in over-throwing Queen Anne’s Whig government, and paving the way for the return of the exiled family. Disappointment at the accession of George I rendered the party of the Pretender more unscrupulous, the mob was excited to go to greater lengths, and the streets of London were occupied by an infuriated rabble, and presented nightly a scene of riot such as can hardly be imagined in our quiet times. It was under these circumstances that the mug-house clubs volunteered, in a very disorderly manner, to be the champions of order, and with this purpose it became a part of their evening’s entertainment to march into the street and fight the Jacobite mob. This practice commenced in the autumn of 1715, when the club called the Loyal Society, which met at the Roebuck, in Cheapside, distinguished itself by its hostility to Jacobitism. On one occasion, at the period of which we are now speaking, the members of this society, or the Mug-house Club of the Roebuck, had burned the Pretender in effigy. Their first conflict with the mob recorded in the newspapers occurred on the 31st of October 1715.

It was the birthday of the Prince of Wales, and was celebrated by illuminations and bonfires. There were a few Jacobite alehouses, chiefly situated on Holborn Hill [Sacheverell’s parish], and in Ludgate Street; and it was probably the frequenters of the Jacobite public-house in the latter locality who stirred up the mob on this occasion to raise a riot on Ludgate Hill, put out the bonfire there, and break the windows which were illuminated. The Loyal Society men, receiving intelligence of what was going on, hurried to the spot, and, in the words of the newspaper report, ‘soundly thrashed and dispersed’ the rioters. The 4th of November was the anniversary of the birth of King William III, and the Jacobite mob made a large bonfire in the Old Jury, to burn an effigy of that monarch; but the mug-house men came upon them again, gave them ‘due chastisement with oaken plants,’ demolished their bonfire, and carried King William in triumph to the Roebuck. Next day was the commemoration of gunpowder treason, and the loyal mob had its pageant.

A long procession was formed, having in front a figure of the infant Pretender, accompanied by two men bearing each a warmin pan, in allusion to the story about his birth, and followed by effigies, in gross caricature, of the pope, the Pretender, the Duke of Ormond, Lord Bolingbroke, and the Earl of Marr, with halters round their necks, and all of which were to be burned in a large bonfire made in Cheapside. The procession, starting from the Roebuck, went through Newgate Street, and up Holborn Hill, where they compelled the bells of St. Andrew’s Church, of which Sacheverell was incumbent, to ring; thence through Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields and Covent Garden to the gate of St. James’s palace; returning by way of Pall-Mall and the Strand, and through St. Paul’s Churchyard. They had met with no interruption on their way, but on their return to Cheapside, they found that, during their absence, that quarter had been invaded by the Jacobite mob, who had carried away all the materials which had been collected for the bonfire. Thus the various anniversaries became, by such demonstrations, the occasions for the greatest turbulence; and these riots became more alarming, in consequence of the efforts which were made to increase the force of the Jacobite mob.

On the 17th of November, of the year just mentioned, the Loyal Society met at the Roebuck, to celebrate the anniversary of the accession of Queen Elizabeth; and, while busy with their mugs, they received information that the Jacobites, or, as they commonly called them, the Jacks, were assembled in great force in St. Martin’s-le-Grand, and preparing to burn the effigies of King William and King George, along with the Duke of Marlborough. They were so near, in fact, that their party-shouts of High Church, Ormond, and King James, must have been audible at the Roebuck, which stood opposite Bow Church. The ‘Jacks’ were starting on. their procession, when they were overtaken in Newgate Street by the mug-house men from the Roebuck, and a desperate encounter took place, in which the Jacobites were defeated, and many of them were seriously injured. Meanwhile the Roebuck itself had been the scene of a much more serious tumult. During the absence of the great mass of the members of the club, another body of Jacobites, much more numerous than those engaged in Newgate Street, suddenly assembled and attacked the Roebuck mug-house, broke its windows and those of the adjoining houses, and with terrible threats, attempted to force the door. One of the few members of the Loyal Society who remained at home, discharged a gun upon those of the assailants who were attacking the door, and killed one of their leaders. This, and the approach of the lord mayor and city officers, caused the mob to disperse; but the Roebuck was exposed to continued attacks during several following nights, after which the mobs remained tolerably quiet through the winter.

With the month of February 1716, these riots began to be renewed with greater violence than over, and large preparations were made for an active mob-campaign in the spring. The mug – houses were refitted, and re-opened with ceremonious entertainments, and new songs were composed to encourage and animate the clubs. Collections of these mug-house songs were printed in little volumes, of which copies are still preserved, though they now come under the class of rare books. The Jacobite mob was again heard gathering in the streets by its well-known signal of the beating of marrow-bones and cleavers, and both sides were well furnished with staves of oak, their usual arms, for the combat, although other weapons, and missiles of various descriptions, were in common use. One of the mum house songs gives the following account of the way in which these riots were carried on:

Since the Tories could not fight,

And their master took his flight,

They labour to keep up their faction;

With a bough and a stick,

And a stone and a brick,

They equip their roaring crew for action.Thus in battle-array,

At the close of the day,

After wisely debating their plot,

Upon windows and stall

They courageously fall,

And boast a great victory they’ve got.But, alas! silly boys!

For all the mighty noise

Of their “High Church and Ormond for ever!”

A brave Whig, with one hand,

At George’s command,

Can make their mightiest hero to quiver.’One of the great anniversaries of the Whigs was the 8th of March, the day of the death of King William; and with this the more serious mug-house riots of the year 1716 appear to have commenced. A large Jacobite mob assembled to their old watch-word, and marched along Cheapside to attack the Roebuck; but they were soon driven away by a small party of the Loyal Society, who met there. The latter then marched in procession through Newgate Street, paid their respects to the Magpie as they passed, and went through the Old Bailey to Ludgate Hill. On their return, they found that the Jacobite mob had collected in great force in their rear, and a much more serious engagement took place in Newgate Street, in which the ‘Jacks’ were again beaten, and many persons sustained serious personal injury. Another great tumult, or rather series of tumults, occurred on the evening of the 23rd of April, the anniversary of the birth of Queen Anne, during which there were great battles both in Cheapside and at the end of Giltspur Street, in the immediate neighbourhood of the two celebrated snug-houses, the Roebuck and the Magpie, which shows that the Jacobites had now become enterprising. Other great tumults took place on the 29th of May, the anniversary of the Restoration, and on the 10th of June, the Pretender’s birthday.

From this time the Roebuck is rarely mentioned, and the attacks of the mob appear to have been directed against other houses. On the 12th of July, the mug-house in Southwark, and, on the 20th, that in Salisbury Court (Read’s Coffee-house), were fiercely assailed, but successfully defended. The latter was attacked by a much more numerous mob on the evening of the 23rd of July, and after a resistance which lasted all night, the assailants forced their way in, and kept the Loyal Society imprisoned in the upper rooms of the house while they gutted the lower part, drank as much ale out of the cellar as they could, and let the rest run out. Read, in desperation, had shot their ringleader with a blunderbuss, in revenge for which they left the coffeehouse-keeper for dead; and they were at last with difficulty dispersed by the arrival of the military. The inquest on the dead man found a verdict of wilful murder against Read; but, when put upon his trial, he was acquitted, while several of the rioters, who had been taken, were hanged. This result appears to have damped the courage of the rioters, and to have alarmed all parties, and we hear no more of the mug-house riots. Their incompatibility with the preservation of public order was very generally felt, and they became the subject of great complaints. A few months later, a pamphlet appeared, under the title of Down with the Mug, or Reasons for Suppressing the Mug-houses, by an author who only gave his name as Sir H. M.; but who seems to have shown so much of what was thought to be Jacobite spirit, that it provoked a reply, entitled The Mug Vindicated.

But the mug-houses, left to themselves, soon became very harmless.