July 5, 1862, Lewis Carroll sat down to start writing the work that would make him famous, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” which began with a story he told to his three girl companions the day before during an outing with the Reverend Robinson Duckworth, where they rowed a boat up the River Isis with the three young girls, and which they called the “golden afternoon.” The three girls were the daughters of scholar Henry Liddell: Lorina Charlotte Liddell, Alice Pleasance Liddell, and Edith Mary Liddell, ages 13, 10, and 8 respectively. The journey began at Folly Bridge, Oxford and ended five miles away in the Oxfordshire village of Godstow. During the trip Carroll, whose real name was Charles Dodgson, told the girls a story that featured a bored little girl named Alice who goes looking for an adventure. The girls loved it, and Alice Liddell asked Dodgson to write it down for her. And the rest, as they say, is history.

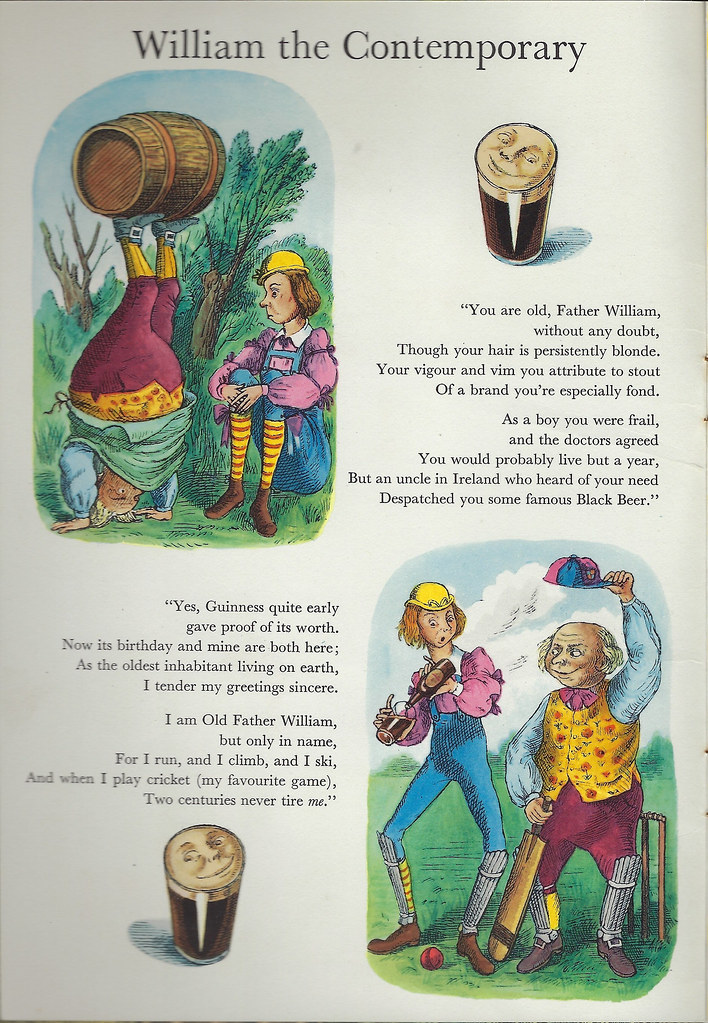

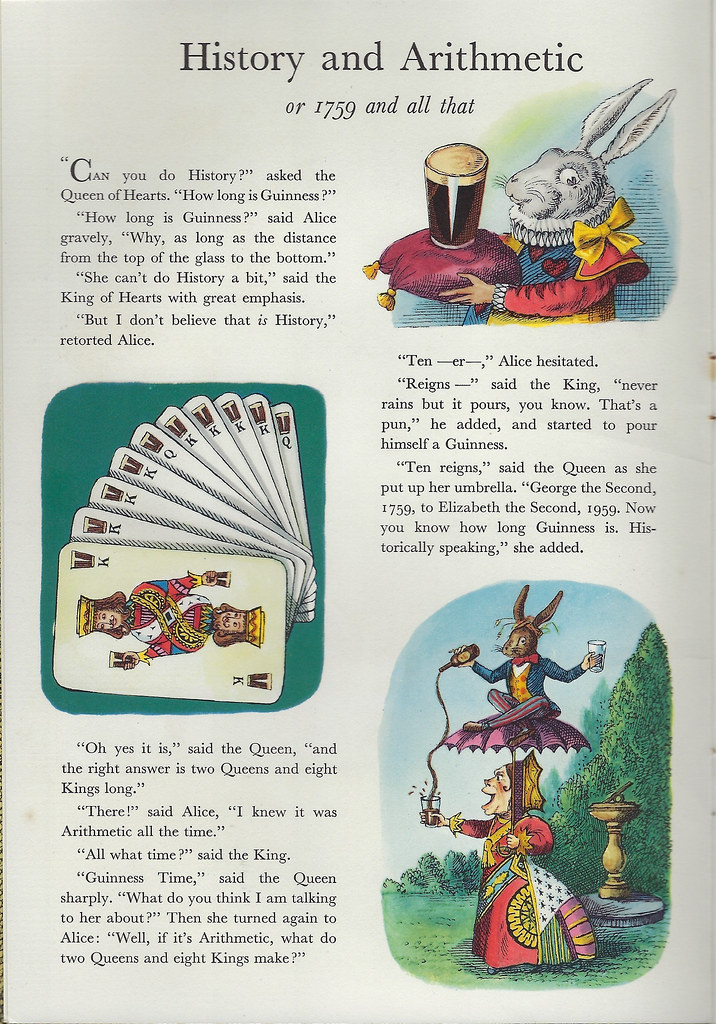

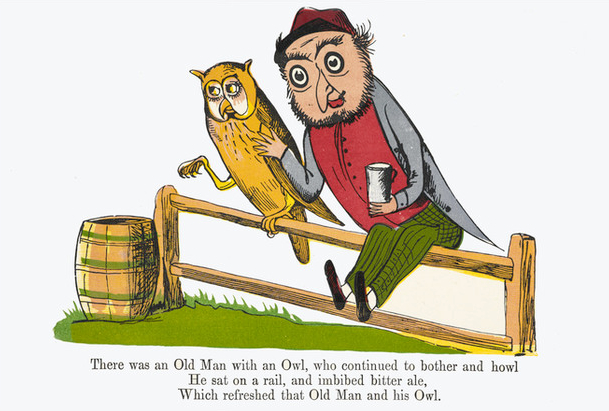

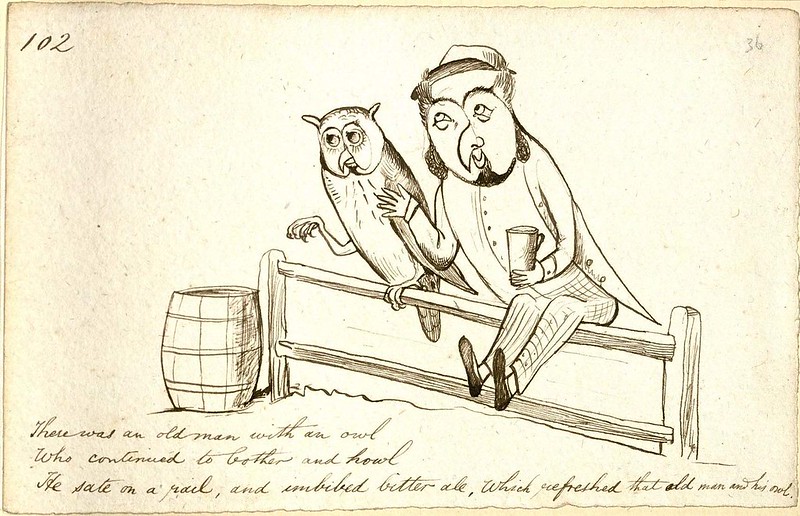

Beginning in the 1930s, Guinness began using Alice in Wonderland and the cast of characters from Carroll’s books in a lot of their advertising. That continued until 1959, and in addition to numerous ads, they also produced five booklets, beginning with “The Guinness Alice” in 1933, and finishing up with “Alice Versary: The Guinness Birthday Book,” which was published to coincide with their 200th anniversary in 1959. All of the booklets and advertising was done by their advertising agency, S.H. Benson Ltd., with illustrations by John Gilroy and later Ronald Ferns. A few years ago, I got a copy of Alice Versary, so here is the whole 16-page booklet.